Where There's Smoke

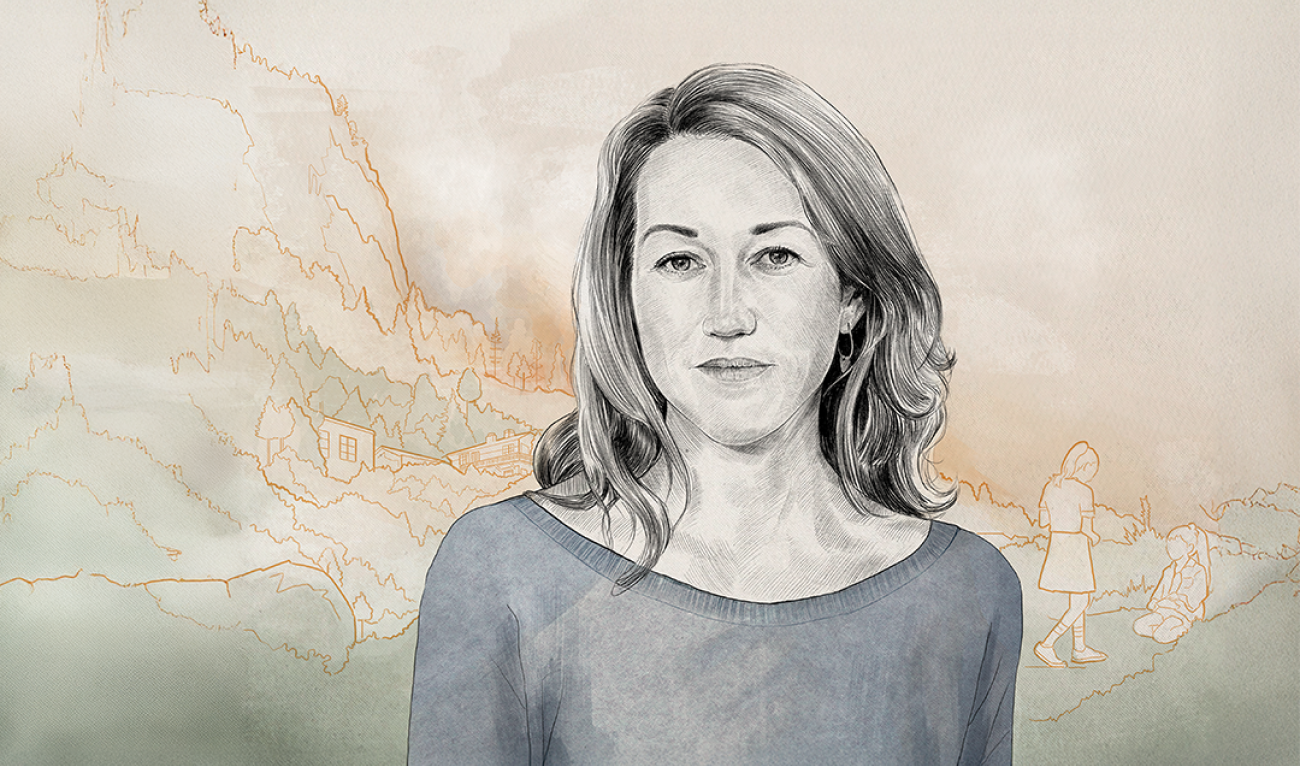

The Tamarack Fire wasn’t one of the largest fires of the 2021 California wildfire season, but it represented a moment of potential crisis for poet Rachel Richardson. In a poem from her new book, Smother, Richardson describes helplessly tracking a map of colored circles that represent the air quality at the summer camp where her children sleep, “cursing when red turns to purple”—darker circles representing a worsening situation—while simultaneously calculating the distance and driving time to reach them in the Sierras from her home in Berkeley. In reality, through a combination of weather, luck, and firefighting, the camp remained safe and the fire was contained, but the poem remains in this moment: The fire burns and Richardson waits, watchful.

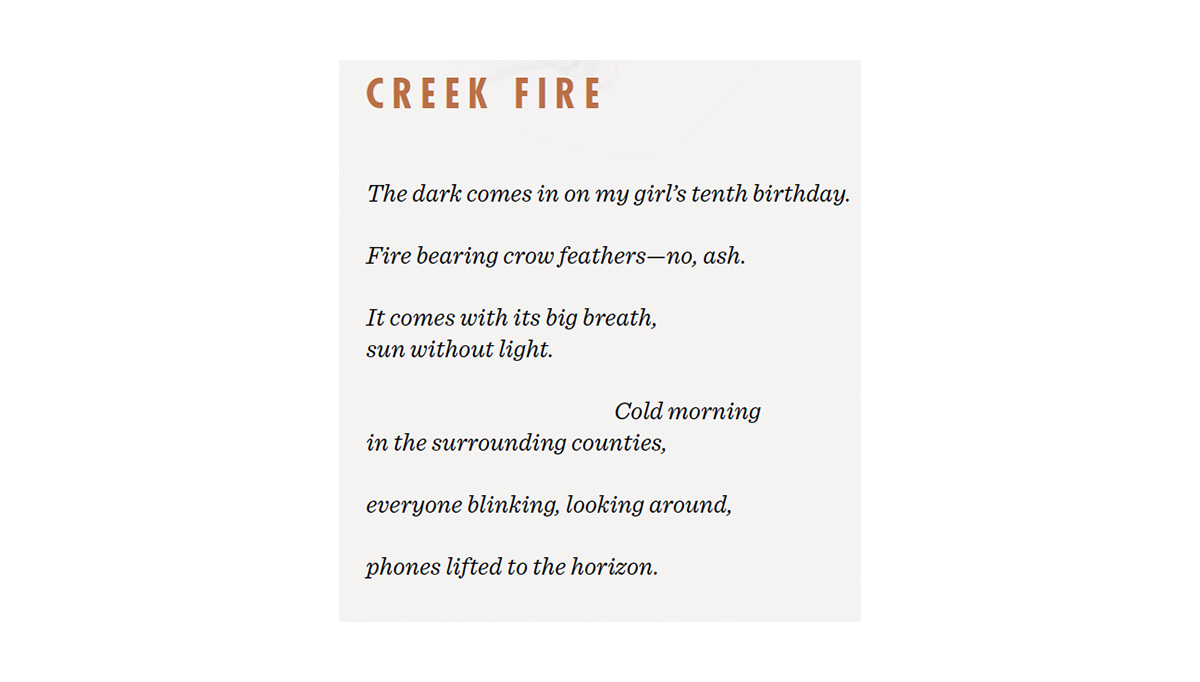

Richardson describes the title Smother as a playful portmanteau of “smoke” and “mother,” but many of its poems capture an increasing sensation that there is no periphery to disaster. “The fires weren’t right at my door,” Richardson says, “but the smoke was always there.” When she began writing the book, she didn’t know she was going to turn to California wildfires as a focus. “At first they were in the background,” she says. “Then they asserted themselves.”

As the frequency and intensity of the wildfires grew, Richardson found herself eager to pursue concrete actions to learn about and fight fires. This began through conversations with friends and neighbors in California about fire safety and practices of intentional, prescribed burns. It developed further when Richardson discovered the inaugural call for the University of Idaho Confluence Lab’s Artists-in-Fire residency, a program that encourages a “proactive and participatory” engagement with wildfires. Richardson knew she had to apply. She recognized in the program a chance to “live inside fire” in an effort to answer a question she sees as central to her life and work: “How do we live together?”

As part of the residency, Richardson completed the National Wildfire Coordinating Group’s “Firefighter Type 2” crewmember wildfire training, which combines online coursework with an arduous pack test and fire shelter deployment. Sasha Michelle White, a doctoral candidate in environmental science at the University of Idaho and one of the organizers of the Artists-in-Fire program, says Richardson stood out among the field of competitive applicants for her writing’s prior engagement with wildfire. “Rachel seemed a perfect candidate to create up-close-and-personal writing about intentional fire.”

Becoming a certified wildland firefighter represents a firsthand commitment to learning the lessons that fire has to teach. “I want to find real answers about how we survive, how we take care of our land and ecosystem, and how we understand what needs to burn,” Richardson says. Jill Bialosky, Richardson’s editor at Norton, recounts the immediacy she felt first reading the manuscript for Smother: “I was completely taken with the way in which the poems address death, wildfires, a raging pandemic, and the ways in which we must protect our loved ones and each other from what we cannot control,” Bialosky says.

Richardson regards Smother as a shift in her personal poetics. “This is a book where I stopped caring about a singular ‘I.’ ” Instead, she thinks the poems are “about how we decide to be together.” The communal theme is relevant not only to wildfires, where a community may be only as safe as its collective commitment to fire prevention, but also to issues within social and domestic spheres.

The mother of two children, ages 12 and 14, and cofounder of Left Margin LIT—a creative writing center in Berkeley—with her husband, poet David Roderick, Richardson found herself reflecting on the community networks that helped her survive moments of isolation that were, at times, “obliterating,” especially during the pandemic. This community includes friendships she made while at Dartmouth. Close friend Giulia Good Stefani ’01 worked for four years as a wildland firefighter in Oregon and California, including for a period when she and Richardson were roommates in the Bay Area. In “Girl Friend Poem: Giulia,” one of several poems in Smother devoted to female friendship, Richardson writes, “For you the fires were the guide. For me, language.” Looking back on those years, she says, “I was teaching myself how to be a writer, while Giulia was teaching herself how to be a firefighter.”

Good Stefani recounts the conversations she and Richardson shared about wildfires and firefighting. “We’ve chatted quite a bit about what my experience firefighting was and how it is becoming exponentially more dangerous and intense,” she says. “It was more seasonal work when I did it.” In addition, Good Stefani recognizes the necessary perspective Richardson gains through wildland firefighter training. “It’s cool that Rachel’s not just looking at [firefighting] from the outside, which is accessible to everyone, but also from the inside of fire and especially as a woman writing from there.”

Richardson—an English major who later earned a master’s in fine arts from the University of Michigan and a master’s in folklore from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—is a distinguished visiting writer at St. Mary’s College of California’s creative writing program. In Smother she also writes of her friendship with Nomi Stone ’03, a poet and professor at the University of Texas at Dallas. Stone refers to Richardson as her “oldest poetry SOS system,” someone always ready to help with a line or poem, a closeness the two have shared for more than 20 years since working as editors of the campus literary magazine Stonefence Review in Sanborn Library. Stone is struck by the way Smother addresses the precariousness of fire and environmental catastrophe while maintaining “a tether to beauty and tenderness.”

Throughout Smother there is a thread of grief, both personal and collective. Richardson started the collection in 2017 after not having written for more than six months following the death of close friend Nina Ellen Riggs. The first poem she wrote, “Questions,” engages with the wide variety of questions people pose online to Google until the tone shifts toward the poem’s close, asking poignantly, “where are you now, come back.” Richardson says, “I thought this was a book about Nina, the death of a friend, and technology—and motherhood, because Nina was a mother.” She was thinking about “how we let technology do so much for us and how we let it separate us.”

As wildfires asserted themselves more clearly in her life and poems, Richardson says new connections emerged in how she was writing about technology and grief as well as wildfires and extreme weather. “We are all second degree to a lot of disasters, but the slow emergency is happening to all of us,” she says, adding that the solution to these disasters demands a break from inherited mindsets. “Fire policy has been incredibly paternalistic,” she says. “It is super macho in the way it has been executed, with a focus on brute strength and heroism. It is not a nurture model.”

A nurture model is precisely what Richardson found this spring at a prescribed burn in Woodland, California. Richardson joined staff members of the nonprofit Cache Creek Conservancy as they used McLeod fire tools to scrape away dead grass and clear a path to direct the fire, with the aim of burning 4 acres of marshy grasses. The “burn boss” for the fire was an elder with Maidu and Wintun tribal affiliation tasked with determining what the group would burn that day.

As Richardson describes it: “The way she contextualized [intentional fire] for us was as an old practice by people who lived deeply on the land and knew it in a way that we don’t now. To have any connection to that mindset was very meaningful as a Californian trying to understand my own place in the ecosystem.” Rather than gasoline or other accelerants that might “contaminate” the fire, the elder taught the traditional method of using tule grass as kindling and urged Richardson and the other workers present to “listen to the fire,” literally, for clues as to how and where it would burn, because, as the elder explained, “Fire talks to us in different ways.”

Bill Carty is a teacher and poet in Seattle who edits prose and poetry for Poetry Northwest.