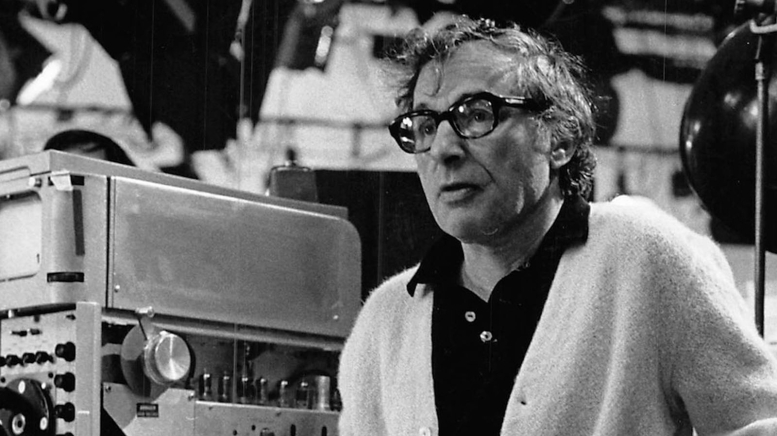

Walter Bernstein pressed his face into the Sicilian dirt as the sky fell in. It was August 1943. The 23-year-old sergeant, a writer for Yank magazine, was with U.S. Gen. George Patton’s army as it fought its way up the coastal road toward Messina. He was trying to survive a few more minutes.

Artillery shells thundered down around him “like death,” he later remembered of Germany’s assault on Allied forces on the Italian island. Bernstein tried desperately to dig deeper with his knees, to gain even a bit more cover. Suddenly, incongruously, he thought of a leather handbag he and his wife had once seen in a New York City shop window. They had loved that bag, the workmanship, the style—but it was too expensive. Now, as the shells exploded around him, he thought, We should have bought the bag. We should have bought the bag.

In the early 1950s Bernstein found himself under fire again, this time for his political beliefs—he was a member of the Communist Party. By then a movie and television screenwriter, he was blacklisted, barred from work by the big studios and networks, and stalked by the FBI. The political ground had shifted so violently that the soldier-journalist widely lauded for his coverage of American GIs in combat was now casually condemned as “un-American.”

Bernstein had seen it coming. In 1949 he attended a concert by Black singer and activist Paul Robeson in Peekskill, New York. An anti-Communist mob, including veterans in uniform, attacked the integrated, left-leaning audience. “Jeering men paraded up and down the road upon us. Among them were delegations from the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars,” Bernstein wrote in his 1996 memoir Inside Out. “I wondered how many of them had read what I had written in Yank, how many like them I had admired and written about, and what we had in common now?”

The future screenwriter arrived in Hanover from Brooklyn at 17 in 1936. Short and intense, he became a fencer, editor-in-chief of the Jacko, and a writer for The Dartmouth. An enthusiastic student activist, he joined the American Student Union and the Young Communists. “I believed in antifascism and international solidarity and the brotherhood and the liberation of man,” he wrote later.

His scathing review in The D of Frank Capra’s 1937 classic, Lost Horizon, derided the film’s escapism. “It seems to us that if a society is rotten, the thing to do is get out and fix it, not retreat to a little Shangri-La and watch it go to pot,” he wrote. Letters poured in. Some called Bernstein a “red.” The paper quickly removed him from the movie beat, but his writing gained positive attention elsewhere. During his junior year he penned a humorous short story called “House Party” about a Dartmouth boy chatting up a hard-drinking chorus girl visiting for the weekend. The New Yorker published it in February 1939. “It was a big thing,” Bernstein said in a 2009 oral history for the Writers Guild. “They paid me $50. Then a couple of weeks later I got another check for $30 because they decided they hadn’t paid me enough.”

Drafted in 1941, he not only wrote for Yank, the U.S. Army’s weekly magazine for GIs, but also contributed war reporting to The New Yorker. He chronicled American troops in action in North Africa, Sicily, and mainland Italy. His biggest scoop came after he secretly trekked for seven days through rugged German-held territory to cadge an exclusive interview with Yugoslav partisan and Communist Party leader Josip Broz Tito. After the war Bernstein published a compilation of his reporting, Keep Your Head Down. Reviewers praised the book as “vastly different” from the run-of-the-mill war memoir. Time noted that he showed “a deft hand for dialogue.” The Louisville Courier-Journal compared him to Hemingway: “Journalism this may be, but it fires the page.”

The acclaim propelled the young veteran to Hollywood in 1947. He first did uncredited screenwriting for All the King’s Men, which won the Academy Award for best picture, and wrote the first draft of Kiss the Blood Off My Hands, an early starring role for Burt Lancaster as a violent and unstable former POW.

But as U.S.-Soviet tensions escalated in the late 1940s, Cold War paranoia about propaganda gripped the country. The U.S. House Un-American Affairs Committee (HUAC) hit Hollywood like a hurricane in 1947, targeting “subversive elements” in the entertainment world. The committee summoned famous actors and movie moguls to testify. Some declared their loyalty to the United States and vowed to rid the industry of “enemy agents, saboteurs, and spies.” Others took the Fifth, staying silent for fear of incriminating themselves. Ten writers and directors refused to do either and instead boldly challenged the congressional committee’s right to question their beliefs. Asked if he was a member of the Communist Party, screenwriter Ring Lardner Jr., one of the 10, said, “I could answer, but I’d hate myself in the morning.” But it was no joke. The “Hollywood Ten,” as they became known, were found guilty of contempt of Congress and wound up in prison for up to a year. Major movie studios soon announced they would not knowingly employ any Communists. The pressure was too much for some. Bernstein’s friend, actor Philip Loeb, who was blacklisted in 1950 but denied being a Communist, died by suicide in 1955.

Bernstein, who had returned to TV work in New York City, didn’t take the hearings seriously at first and shrugged off suggestions that the Communist Party was a menace. “The charge that we wanted to overthrow the government by force and violence was ludicrous. Nothing I had ever done or intended or even thought was designed for that.”

When former FBI agents who ran the right-wing newsletter Counterattack outed 151 suspected Communists in the 1950 booklet Red Channels, Bernstein made the list. He was unapologetically proud of his politics: “There were eight listings for me, and they were all true,” he later said. He was a member of the Communist Party until the mid-1950s. He had written for left-wing publications. He had opposed the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. He had supported the rights of Black veterans. “Speech was now punishable,” he wrote later. “You did not have to do anything, you had only to advocate.” One of Bernstein’s five children, Nick ’84, tells DAM that he once asked his father if he had been angry about being named. His response: “I would have been angry if I wasn’t.”

These days an entertainer might be booted from a movie or show for social media posts deemed politically incorrect or repugnant, but the blacklist was more insidious than modern-day “cancel culture.” It was backed by the power of government: congressional subpoenas, FBI investigations, and the threat of prison.

No studio would hire Bernstein, but his talents were still in demand. Through the 1950s he wrote TV shows for sympathetic producers under pseudonyms, using “fronts”—real people who would claim the script as theirs if anyone asked. “It was a bad time in every way,” he said. FBI agents frequently showed up to question him. “They would stop you getting on a bus or coming out of the subway, all very polite,” he said, “but it was letting you know they knew where you were.” Ever present was the implied promise that if he would testify and name names of fellow Communists, he could resume his career.

Bernstein teamed up with two other blacklisted screenwriters, Abraham Polonsky and Arnold Manoff. If one got a job and another really needed the money, they would pass it along. The three went to work for young director Sydney Lumet on the CBS program You Are There, hosted by Walter Cronkite. They shared a camaraderie similar to that of the GIs Bernstein had covered in the war. “There was a generosity of spirit that was very valuable to me, that I miss now,” he later wrote.

The blacklist destroyed other friendships. Budd Schulberg ’36, who wrote the screenplay to On the Waterfront and helped F. Scott Fitzgerald on Winter Carnival, had mentored Bernstein. When Schulberg named names to HUAC in 1951, Bernstein felt betrayed. Nick Bernstein said his father could not forgive that and refused to patch things up.

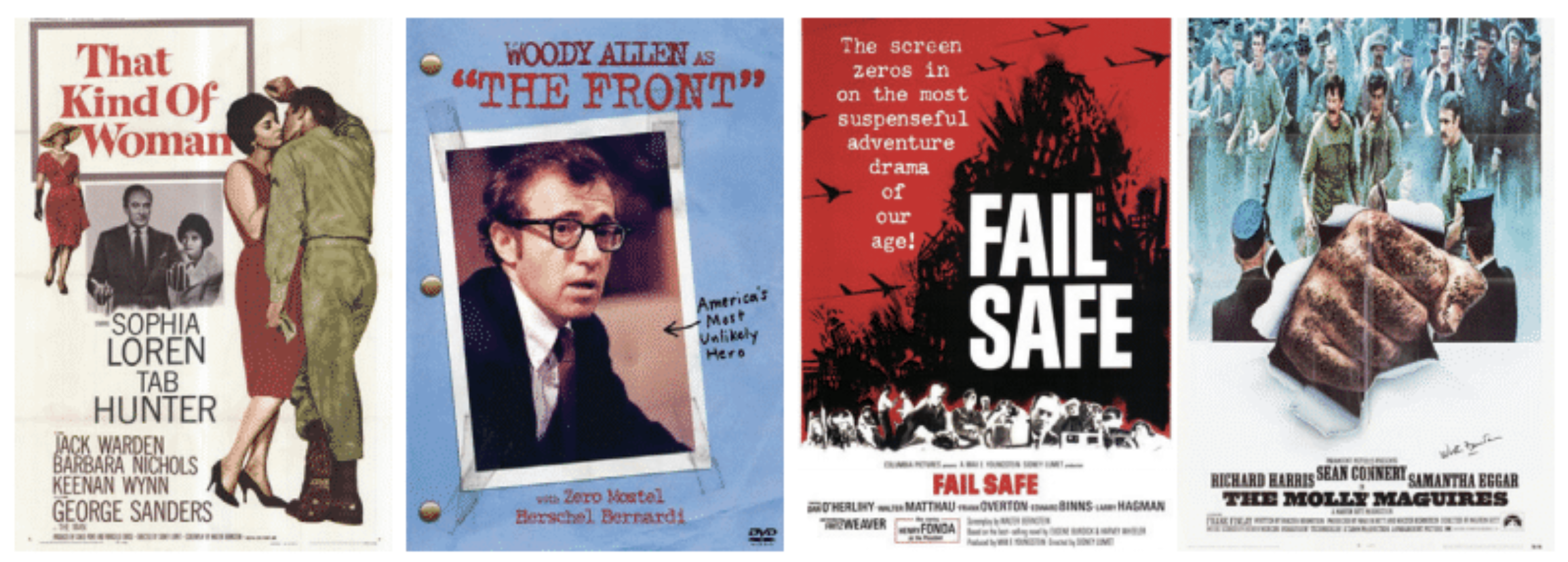

National paranoia and the power of the blacklist had begun to fade when Lumet hired Bernstein in 1957 to write That Kind of Woman (1959), starring Sophia Lauren. HUAC had finally subpoenaed Bernstein, but he dodged it to finish the screenplay, and Lumet credited him for it by name.

The screenwriter’s political point of view permeates some of his later films. Fail Safe (1964) laid bare the potential horror of an accidental nuclear crisis. The Molly Maguires (1970), his personal favorite, starred Sean Connery in a sympathetic portrayal of Irish-American coal miners battling exploitation by the owners.

His focus was always on the words. “I don’t think in terms of images that much,” Bernstein said. “I am most at home writing about two characters in a room.” He zeroed in on character, conflict, and, most importantly, meaning. He loved to tell the tale about a friend visiting Henry David Thoreau at Walden Pond to excitedly inform him that Samuel Morse had sent the world’s first telegraph message. “But,” Thoreau is said to have asked, “what did it say?”

Bernstein’s best-known film, The Front (1976)—for which he was nominated for an Oscar—told his own story, with a twist. He and director Martin Ritt, a frequent collaborator who had been blacklisted, tried to persuade studios to do a film on the blacklist, but no one would touch it. “Then we got the idea of coming at it sideways,” said Bernstein, by making a dark comedy that focused on the front instead of the writers. They convinced Woody Allen to star and hired as many blacklist veterans as they could, including actor Zero Mostel.

Many of Bernstein’s screenplays were adaptations of novels, but he refused to be handcuffed by the original work. “It’s not so much a matter of adaptation as transformation,” he said. His adaptation of Dan Jenkins’ 1971 football novel Semi-Tough was so different from the book that Jenkins threw the screenplay at the wall in frustration. Directed by Michael Ritchie and starring Burt Reynolds, Kris Kristofferson, and Jill Clayburgh, the re-imagined story went on to become one of the top-grossing movies of 1977.

Bernstein worked into his 90s. “It was like watching a woodpecker in heat,” says his son Nick. “Writing was his life force.” HBO commissioned a number of Bernstein’s scripts in the 1990s, including the Emmy-winning Miss Evers’ Boys (1997) about the U.S. government’s controversial use of Black men as guinea pigs for syphilis research. “Given Walter’s own history as both a writer and political animal, he was an inspirational writer for us to go to,” former HBO Films President Colin Callender told Variety in 2014. Bernstein’s last big project was the BBC mystery miniseries Hidden (2011), which he co-wrote at age 90. He died in January at age 101, having written 16 movies, eight television movies, and more than 35 TV episodes, most while he was on the blacklist.

More than 50 years after the end of World War II, Bernstein and his fourth wife, Gloria Loomis, returned to Sicily. They drove the road Patton’s troops had traveled, past the place where Bernstein had flattened himself in the dirt, up a winding track to a mountain town that he had entered with American troops in 1943. “There were three men Walter’s age on the bench,” Loomis says. “I speak Italian so I spoke to them. ‘My husband was here with the first American troops. He was in this square.’ ” One of the men stood up. He had been there, too. “It was a very emotional moment,” Loomis recalls.

Bernstein frequently visited Dartmouth and other colleges to talk to students about the blacklist and screenwriting. He exuded humor and modesty. A Dartmouth student asked him in 2002 how he prepared to write the movie Fail Safe. Bernstein’s reply: “I read the book.”

The defining moment of his life, he said, was being smuggled in to watch the shoot of a scene he had written during the blacklist. The script had been submitted under the name of a woman who was then gadding around the set taking compliments for her great writing. Watching with a strange detachment, Bernstein suddenly realized he didn’t care that much about the recognition. It was the writing that counted, the chance to say what you wanted. Recognition was nice, but not so important.

“You will be tested if you go to Hollywood,” he said in his 2009 oral history for the Writers Guild. “How much will you compromise and what will you compromise? If you’re not clear about that, if you lose that, then you have lost yourself.…You have to know who you are at the end of the day.”

Rick Beyer is a documentary filmmaker, author, and cohost of the History Happy Hour.