The sport of biathlon, which combines cross-country skiing and rifle marksmanship, has a tiny following in the United States—unlike Europe, where television ratings claim more than 900 million views each year—so it’s not surprising American teams have seen only sporadic success.

Thanks in part to Sara Studebaker ’07, Susan Dunklee ’08 and Laura Spector ’10, who made up three quarters of the U.S. World Cup team last fall, that’s changing.

Studebaker and Spector were last year’s heroes: Spector became the first American woman in six years to qualify for the prestigious mass start event that is limited to the top 30 female athletes in the sport, and Studebaker placed 14th in a World Cup race in Maine, a similarly rare result.

Dunklee saw her first World Cup action in November and made the most of her seven starts before Christmas, collecting a 28th-place finish and leading the U.S. women in four races. It was one of the most successful debuts ever for a U.S. biathlete.

All three former Dartmouth cross-country ski team members will likely compete at the World Championships in Ruhpolding, Germany, in March—something akin to traveling to Yankee Stadium to play in the World Series, but with cowbells, gunpowder and better beer. Competing in the heartland of biathlon will be a true test of how far the U.S. program—led by these Dartmouth alums—has come.

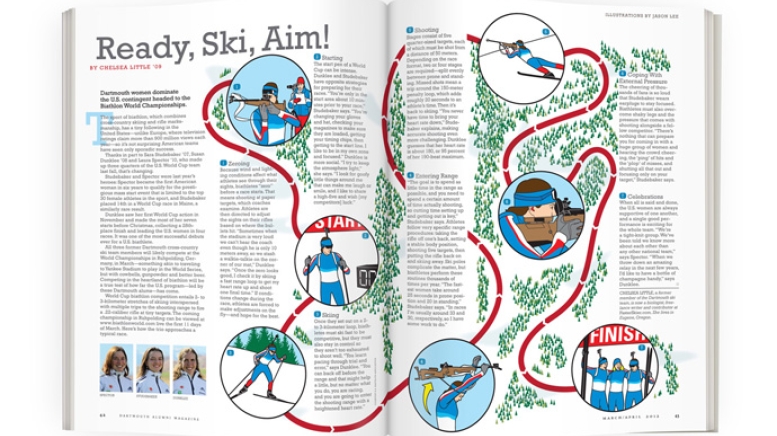

World Cup biathlon competition entails 2- to 3-kilometer stretches of skiing interspersed with multiple trips to the shooting range to fire a .22-caliber rifle at tiny targets. The coming championship in Ruhpolding can be viewed at www.biathlonworld.com live the first 11 days of March. Here’s how the trio approaches a typical race.

Zeroing

Because wind and lighting conditions affect what athletes see through their sights, biathletes “zero” before a race starts. That means shooting at paper targets, which coaches examine. Athletes are then directed to adjust the sights on their rifles based on where the bullets hit. “Sometimes when the stadium is very loud we can’t hear the coach even though he is only 10 meters away, so we stash a walkie-talkie on the corner of our mat,” Dunklee says. “Once the zero looks good, I check it by skiing a fast range loop to get my heart rate up and shoot one final time.” If conditions change during the race, athletes are forced to make adjustments on the fly—and hope for the best.

Starting

The start pen of a World Cup can be intense. Dunklee and Studebaker have opposite strategies for preparing for their races. “You’re only in the start area about 10 minutes prior to your race,” Studebaker says. “You’re changing your gloves and hat, checking your magazines to make sure they are loaded, getting your timing chips, then getting to the start line. I like to be in my own zone and focused.” Dunklee is more social. “I try to keep the atmosphere light,” she says. “I look for goofy little things around me that can make me laugh or smile, and I like to share a high-five and wish [my competitors] luck.”

Skiing

Once they set out on a 2- to 3-kilometer loop, biathletes must ski fast to be competitive, but they must also stay in control so they aren’t too exhausted to shoot well. “You learn pacing through trial and error,” says Dunklee. “You can back off before the range and that might help a little, but no matter what you do, you are racing, and you are going to enter the shooting range with a heightened heart rate.”

Shooting

Stages consist of five quarter-sized targets, each of which must be shot from a distance of 50 meters. Depending on the race format, two or four stages are required—split evenly between prone and standing. Missed shots mean a trip around the 150-meter penalty loop, which adds roughly 20 seconds to an athlete’s time. Then it’s back to skiing. “You never have time to bring your heart rate down,” Studebaker explains, making accurate shooting even more challenging. Dunklee guesses that her heart rate is about 180, or 95 percent of her 190-beat maximum.

Entering the Range

“The goal is to spend as little time in the range as possible, and you need to spend a certain amount of time actually shooting, so cutting time setting up and getting out is key,” Studebaker says. Athletes follow very specific range procedures: taking the rifle off one’s back, setting a stable body position, shooting five targets, then putting the rifle back on and skiing away. Ski poles complicate the matter, but biathletes perform these routines thousands of times per year. “The fastest women take around 25 seconds in prone position and 20 in standing,” Studebaker says. “In races I’m usually around 33 and 30, respectively, so I have some work to do.”

Coping With External Pressure

The cheering of thousands of fans is so loud that Studebaker wears earplugs to stay focused. Biathletes must also overcome shaky legs and the pressure that comes with shooting alongside a fellow competitor. “There’s nothing that can prepare you for coming in with a huge group of women and hearing the crowd cheering, the ‘ping’ of hits and the ‘plop’ of misses, and shutting all that out and focusing only on your target,” Studebaker says.

Celebrations

When all is said and done, the U.S. women are always supportive of one another, and a single good performance is exciting for the whole team. “We’re a tight-knit group. We’ve been told we know more about each other than any other national team,” says Spector. “When we throw down an amazing relay in the next few years, I’d like to have a bottle of champagne handy,” says Dunklee.

Chelsea Little, a former member of the Dartmouth ski team, is a biologist, freelance writer and contributor to FasterSkier.com. She lives in Eugene, Oregon.