Scions of two movie moguls. Roommates at Dartmouth. Ardent young communists. Collaborators on a historic flop. The traitor and the betrayed. An Oscar-winning author and a beloved academic.

They were all that and best friends for life—except for 13 years in the middle.

It sounds like a movie, but the almost lifelong friendship of Budd Schulberg and Maurice Rapf was far too big for the movies, despite taking place in and around them. If anything, it’s an epic streaming series, a bingeworthy tale sprawling across the 20th century, cast with film stars and literary legends, studio titans, and a congressional committee. It encompasses the Depression and the blacklist, arcs from Los Angeles to Moscow, and repeatedly returns to Hanover like a cat finding its way home.

Start with two little boys growing up a block apart and running free in silent-era Hollywood, sons of celluloid pioneers at rival studios. Maurice’s father, Harry Rapf, was the No. 3 executive at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), while Budd’s dad was B.P. Schulberg, the production head who virtually ran Paramount. While their fathers were overseeing some of the biggest box office hits of the day, Maury and Budd plundered the MGM prop room for costumes from Ben-Hur and The Big Parade, played on the desert fort set from Beau Geste, and raided the fig tree on the MGM lot to lob fruit at Greta Garbo and other stars. They raised homing pigeons, cut classes to watch four movies a day, and lived a carefree existence in the land of make-believe as it was taking shape.

“They were like brothers,” says Maurice’s daughter, Dartmouth visiting professor Joanna Rapf. “They were inseparable as kids. They raised their pigeons together; they did ham radio together. I grew up hearing stories about their Halloween pranks.” It was the friendliest of rivalries, too. In his 1981 memoir, Moving Pictures, Schulberg wrote, “Instead of saying, ‘My pop c’n lick your pop,’ we literally used to say, ‘My father’s studio c’n make better pictures than your father’s.’ ”

Reality came knocking soon enough. The twin calamities of talking pictures in 1927 and the Great Depression in 1929 rocked the film industry. B.P. Schulberg’s career was tied to his most famous discovery, screen sexpot Clara Bow, and when she left Paramount, he was forced out. Harry Rapf was sidelined by a heart attack in 1933 and never regained his footing at MGM. Both men had involvements with actresses that disillusioned their sons: B.P. Schulberg abandoned his family in 1931 for Sylvia Sidney, and Harry Rapf may or may not have had an affair with an upcoming starlet named Lucille LeSueur, whom he dubbed Joan Crawford. (Maurice Rapf told an interviewer that he was never sure whether his father had a physical relationship with Crawford, “but I know my mother believed he did.”)

When it came time to leave Los Angeles for college, Budd Schulberg enrolled at Dartmouth on the recommendation of independent producer Walter Wanger, class of 1915, the only early Hollywood mogul with an Ivy League education. Rapf went to Stanford—where he lasted a year and a half before transferring to Hanover and rooming with his friend.

They were inseparable as kids. They raised their pigeons together; they did ham radio together. I grew up hearing stories about their Halloween pranks.” -Joanna Rapf

Budd majored in sociology, Maurice in English; Maurice acted in theater and wrote plays, while Budd wrote for the Jack-O-Lantern and served as editor of The Daily Dartmouth, often sleeping overnight in the paper’s offices. The friends collaborated on a musical satire called Banned in Boston and grew increasingly politically active. It was an era when youthful disenchantment with the failures of capitalism led many to support labor causes. When Schulberg’s Daily D reported on the Vermont Marble strike of 1935, the paper’s support of struggling quarry workers led to warnings from the College administration—and donations of food, clothing, and money from around the country.

It was also an era when disenchantment led to dalliances with communism and an interest in the Soviet experiment, which the two friends experienced firsthand during a summer study program in Moscow. Rapf returned cautiously convinced, and back in Hollywood after graduation he joined the Communist Party; Schulberg joined, too, although less enthusiastically. This would lead in time to a friendship dashed on the rocks of history.

The Carnival Fiasco

Before that, the two played a role in one of the most storied cinematic disasters of its era: the legendary 1939 stinker Winter Carnival, filmed in Hanover and for years shown to incoming Dartmouth students as a ritual form of punishment. The tale has oft been told but to recap: Schulberg was sent to Dartmouth by producer Wanger to write the film’s screenplay with F. Scott Fitzgerald, at that point an alcoholic wreck far from the pinnacle of his 1920s fame. Fitzgerald had been on the wagon until Schulberg père gifted him with a bottle of champagne for the plane trip east. The writer holed up on a Hanover Inn binge, making an appearance only to fall down the stairs at a party in his honor.

Fitzgerald was fired—and Rapf, who was driving across the country with his new wife, actress Louise Seidel, was enlisted to finish the script with Schulberg. Maurice’s agent told him to take the job, as it would raise the young writer’s profile in Hollywood. Quite the opposite: In years to come, as Rapf wryly told it, he’d be vying for a studio screenwriting gig and whenever it looked as though it was all set, they’d say, “‘Didn’t you work on Winter Carnival?’ And I wouldn’t get the job.”

What Schulberg got out of the experience was his third novel, The Disenchanted, a thinly veiled fictionalization of the Winter Carnival debacle published in 1950. He’d already made a splash as a writer with the 1941 bestseller, What Makes Sammy Run, a brutally honest portrait of an amoral up-and-coming studio striver, and he followed that up in 1947 with The Harder They Fall, which became a 1956 Humphrey Bogart movie. Rapf, for his part, worked as a screenwriter but increasingly found himself involved in the creation of the Screen Writers Guild.

Throughout this period, the old friendship held fast, in person and by telephone. “I remember the Saturday morning phone calls to place the bets on the College football games,” says Joanna Rapf. “I mean, that was really important. It was a nickel and dime thing, but they always paid up.”

During World War II, Schulberg worked overseas in an Office of Strategic Services film unit headed by director John Ford, ultimately documenting German concentration camps and collecting evidence for the Nuremberg trials. Rapf stayed stateside writing propaganda films for the Office of Inter-American Affairs. Not long after the war ended, Rapf quit the Communist Party. “When I got back from the Soviet Union,” Rapf said later, “[producer David] Selznick said to me, ‘You’ve got to choose between being a moviemaker and being a communist.’ In effect, what I chose to do in 1947 was to be a moviemaker.”

“Scoundrel Time”

Rapf worked on Disney’s Cinderella, making the heroine less passive and more of a rebel, although by the time the movie came out in 1950, he was on the Hollywood blacklist and never received credit. He’d sensed the storm coming, though, and moved East with Louise and their three children, settling in New York City and living off the rent of his Los Angeles house while getting under-the-radar writing jobs on animation and industrial films—and dropping in on Dartmouth for a brief spell to advise students interested in film. That would pay dividends later.

It was what playwright Lillian Hellman called “scoundrel time,” when the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) chased down everyone who’d been an idealistic communist or “fellow traveler” 15 years earlier and forced them to inform on each other, destroying careers and in some cases lives. Rapf was named as a communist by a number of “friendly witnesses.” “No friend of mine ever named me,” he said later. “Only the people I hated did.” He managed to avoid testifying in front of the committee because—and this is true—he came down with the mumps.

Schulberg, however, named names. Not his old friend Maury, of course. “Budd did not name him,” Joanna Rapf says. “[He] only named names that had already been named to keep his conscience clear. But to my father, it was not conscionable to cooperate with the committee.” The two men didn’t speak for 13 years, and Schulberg became a pariah to a sizable portion of the Hollywood community.

During that time, two things happened. Schulberg’s career soared further with his screenplay for the 1954 drama On the Waterfront, the Marlon Brando classic directed by Elia Kazan, who also had been a friendly witness for HUAC. Both director and screenwriter won Oscars—two of the film’s eight—and Waterfront, with its plot about a New York dockworker (Brando) testifying about union gangsterism, was seen by many as an apologia or a rat’s rationalization from the two men responsible for making the movie. (Schulberg denied this throughout his life, saying the story came from two years of research in and around the docks.)

Schulberg continued to ride high through the 1950s, writing the script for A Face in the Crowd, about a populist TV star turned political megalomaniac. The 1957 film looks even more relevant now than when it came out. Meanwhile, Rapf was back East, moving from writing sponsored industrial films to a busy career directing them. One of Rapf’s first turns behind the camera had been My First Week at Dartmouth, a College-sponsored recruitment film in 1950 starring Buck Zuckerman ’52, later to become the writer-actor Buck Henry. (This film, too, was inflicted upon incoming freshmen until the 1980s.) Rapf also wrote movie reviews for Life magazine, and in 1967 he officially joined Dartmouth as a visiting lecturer in drama, advising students in film production.

That was the start of a new era at the College. Rapf developed a film studies and production curriculum to complement the student-run Dartmouth Film Society, founded in 1949 and now the oldest continually running college film society in the country. The movies had entered the academy, and Dartmouth was part of the first wave.

Reunited

In the fall of 1965, a friendship was finally renewed, fittingly enough on the streets of Hanover. Maurice’s son Bill and Budd’s son Stephen entered the freshman class of ’68 the same year, and, according to Joanna Rapf, “Budd and Maurice met each other outside of the Hanover Inn. It was Louise, my mother, who said, ‘This has gone on long enough. Both your sons are enrolling now at Dartmouth. Shake hands and be friends again.’ And they did. Time had passed since the hearings, and the friendship meant everything.”

The next Saturday, the weekly betting on College games resumed by telephone, an excuse to talk about the world and the movies, good and bad, they’d seen. The conversation continued for decades. In the years to come, Budd cemented his status as an aging lion of American letters while Maury inculcated generations of students—including this writer—into the mysteries of screenwriting and filmmaking with humble wisdom and plangent wit. To be taught by him was to have the entire history of American movies at the table, underlined by a sense of ethics and compassion that didn’t speak loudly and didn’t have to.

Professor Rapf retired in 2001 and died at 88 in April 2003. The Maurice H. Rapf ’35 Award for Outstanding Achievement in Film and Media Studies is given annually to graduating seniors for “significant achievement and contribution” to film at Dartmouth. Schulberg lived to 95, dying in 2009 at his home in Westhampton Beach, New York.

In many ways, the two men could not have been more different. Budd was effusive, expansive; Maury was quietly and penetratingly direct. Budd married four times; Maury and Louise stayed married for 54 years until her death in 1993. Budd’s novels and films outlive him; Maury lives on in the memories and careers of the students he mentored.

Yet the bond held to the last. “I remember being in the hospital room as he was dying,” says Rapf’s daughter Joanna, “and one day, he said, ‘Oh my God, it’s Budd’s birthday.’ I think he died the next day.”

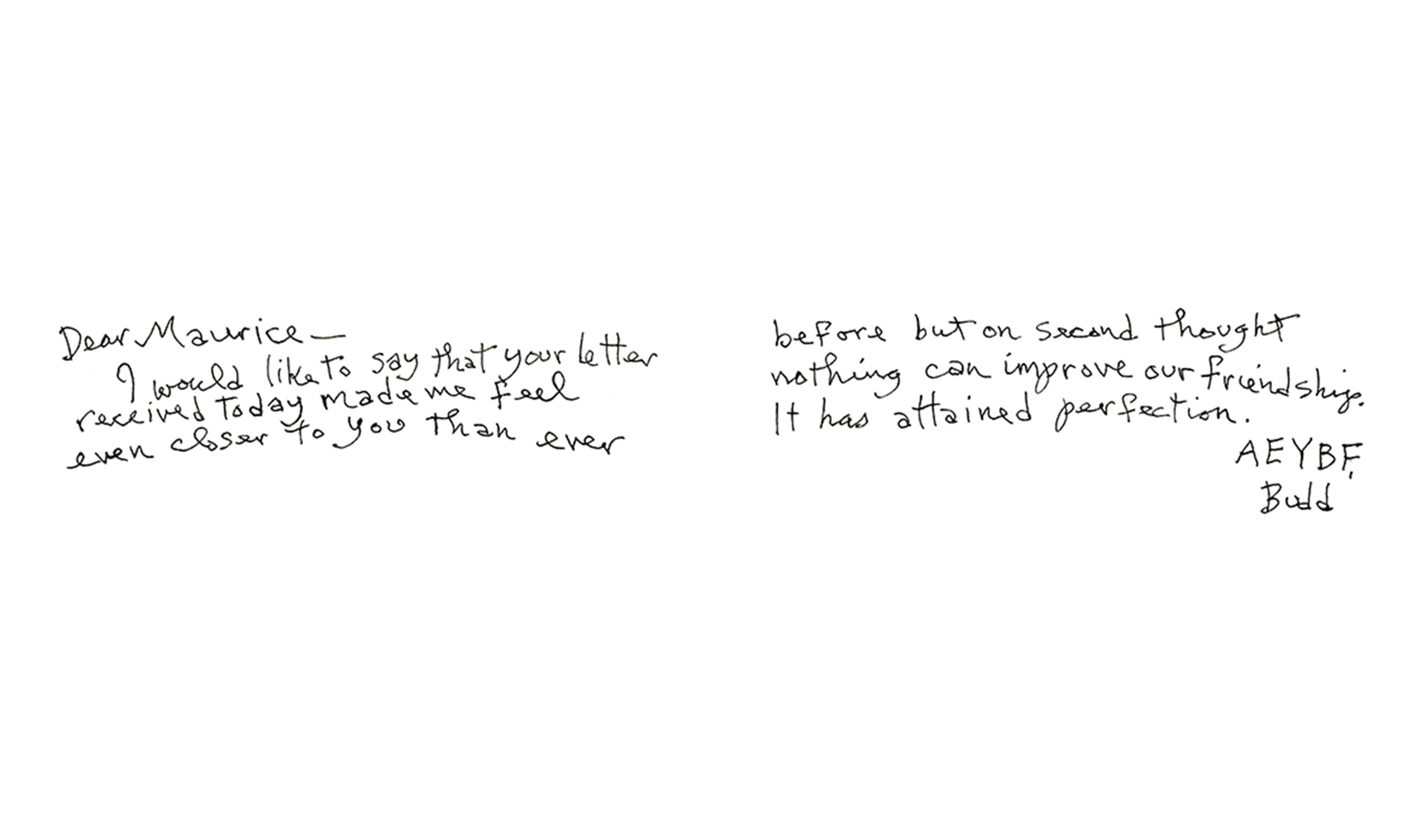

Schulberg spoke at Rapf’s memorial service, telling all the old stories about the fig tree and the pigeons, Dartmouth and Hollywood, the bad years and the good. “All of our lives,” he told the assembled listeners, “from the age of about 11 or 12, when we wrote to each other, we always signed our letters ‘AEYBF,’ which stood for ‘As Ever Your Best Friend. And that’s the way I’m signing this—As Ever Your Best Friend. Thank you.”

Ty Burr, film critic and author of the newsletter Ty Burr’s Watch List, is a frequent contributor. He wrote “America’s First Civil War” [November/December 2025].