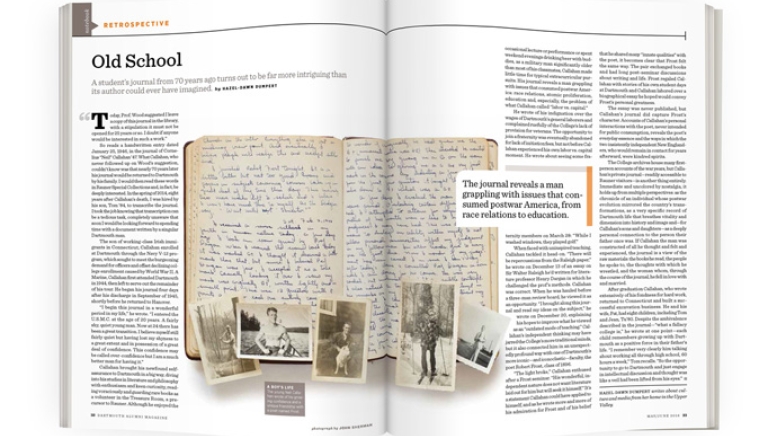

“Today, Prof. Wood suggested I leave a copy of this journal in the library, with a stipulation it must not be opened for 25 years or so. I doubt if anyone would be interested in such a work.”

So reads a handwritten entry dated January 25, 1946, in the journal of Cornelius “Neil” Callahan ’47. What Callahan, who never followed up on Wood’s suggestion, couldn’t know was that nearly 70 years later his journal would be returned to Dartmouth by his family. I would then read these words in Rauner Special Collections and, in fact, be deeply interested. In the spring of 2014, eight years after Callahan’s death, I was hired by his son, Tom ’84, to transcribe the journal. I took the job knowing that transcription can be a tedious task, completely unaware that soon I would be looking forward to spending time with a document written by a singular Dartmouth man.

The son of working-class Irish immigrants in Connecticut, Callahan enrolled at Dartmouth through the Navy V-12 program, which sought to meet the burgeoning demand for officers and offset declining college enrollment caused by World War II. A Marine, Callahan first attended Dartmouth in 1944, then left to serve out the remainder of his tour. He began his journal four days after his discharge in September of 1945, shortly before he returned to Hanover.

“I begin this journal in a wonderful period in my life,” he wrote. “I entered the U.S.M.C. at the age of 20 years. A fairly shy, quiet young man. Now at 24 there has been a great transition. I believe myself still fairly quiet but having lost my shyness to a great extent and in possession of a great deal of confidence. This confidence may be called over-confidence but I am a much better man for having it.”

Callahan brought his newfound self-assurance to Dartmouth in a big way, diving into his studies in literature and philosophy with enthusiasm and keen curiosity, reading voraciously and guarding rare books as a volunteer in the Treasure Room, a precursor to Rauner. Although he enjoyed the occasional lecture or performance or spent weekend evenings drinking beer with buddies, as a military man significantly older than most of his classmates, Callahan made little time for typical extracurricular pursuits. His journal reveals a man grappling with issues that consumed postwar America: race relations, atomic proliferation, education and, especially, the problem of what Callahan called “labor vs. capital.”

He wrote of his indignation over the wages of Dartmouth’s general laborers and complained ruefully of the College’s lack of provision for veterans. The opportunity to join a fraternity was eventually abandoned for lack of initiation fees, but not before Callahan experienced his own labor vs. capital moment. He wrote about seeing some fraternity members on March 28: “While I washed windows, they played golf.”

When faced with uninspired teaching, Callahan tackled it head-on. “There will be repercussions from the Raleigh paper,” he wrote on December 13 of an essay on Sir Walter Raleigh he’d written for literature professor Henry Dargan in which he challenged the prof’s methods. Callahan was correct. When he was hauled before a three-man review board, he viewed it as an opportunity. “I brought along this journal and read my ideas on the subject,” he wrote on December 20, explaining his hopes to improve what he viewed as an “outdated mode of teaching.” Callahan’s independent thinking may have jarred the College’s more traditional minds, but it also connected him in an unexpectedly profound way with one of Dartmouth’s more iconic—and iconoclastic—faculty, the poet Robert Frost, class of 1896.

“The light broke,” Callahan enthused after a Frost seminar. “His wonderful, independent nature does not want literature laid out for him but will seek it himself.” It’s a statement Callahan could have applied to himself, and as he wrote more and more of his admiration for Frost and of his belief that he shared many “innate qualities” with the poet, it becomes clear that Frost felt the same way. The pair exchanged books and had long post-seminar discussions about writing and life. Frost regaled Callahan with stories of his own student days at Dartmouth and Callahan labored over a biographical essay he hoped would convey Frost’s personal greatness.

The essay was never published, but Callahan’s journal did capture Frost’s character. Accounts of Callahan’s personal interactions with the poet, never intended for public consumption, reveals the poet’s everyday essence and the ways in which the two insistently independent New Englanders, who would remain in contact for years afterward, were kindred spirits.

The College archives house many first-person accounts of the war years, but Callahan’s private journal—readily accessible to Rauner visitors—is another thing entirely. Immediate and uncolored by nostalgia, it holds up from multiple perspectives: as the chronicle of an individual whose postwar evolution mirrored the country’s transformations, as a very specific record of Dartmouth life that breathes vitality and dimension into history and image and—for Callahan’s sons and daughters—as a deeply personal connection to the person their father once was. If Callahan the man was constructed of all he thought and felt and experienced, the journal is a view of the raw materials: the books he read, the people he spoke to, the thoughts with which he wrestled, and the woman whom, through the course of the journal, he fell in love with and married.

After graduation Callahan, who wrote extensively of his fondness for hard work, returned to Connecticut and built a successful excavation business. He and his wife, Pat, had eight children, including Tom and Jean, Tu’80. Despite the ambivalence described in the journal—“what a fallacy college is,” he wrote at one point—each child remembers growing up with Dartmouth as a positive force in their father’s life. “I remember very clearly him talking about working all through high school, 60 hours a week,” Tom recalls. “So the opportunity to go to Dartmouth and just engage in intellectual discussion and thought was like a veil had been lifted from his eyes.”

Hazel-Dawn Dumpert writes about culture and media from her home in the Upper Valley.