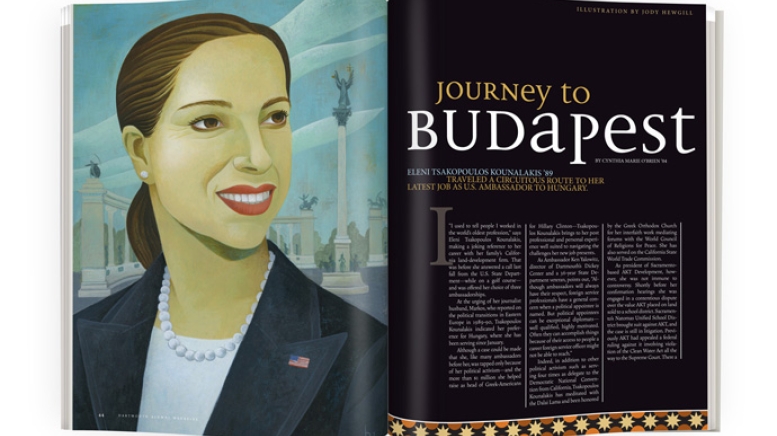

“I used to tell people I worked in the world’s oldest profession,” says Eleni Tsakopoulos Kounalakis, making a joking reference to her career with her family’s California land-development firm. That was before she answered a call last fall from the U.S. State Department—while on a golf course—and was offered her choice of three ambassadorships.

At the urging of her journalist husband, Markos, who reported on the political transitions in Eastern Europe in 1989-90, Tsakopoulos Kounalakis indicated her preference for Hungary, where she has been serving since January.

Although a case could be made that she, like many ambassadors before her, was tapped only because of her political activism—and the more than $1 million she helped raise as head of Greek-Americans for Hillary Clinton—Tsakopoulos Kounalakis brings to her post professional and personal experience well suited to navigating the challenges her new job presents.

As Ambassador Ken Yalowitz, director of Dartmouth’s Dickey Center and a 36-year State Department veteran, points out, “Although ambassadors will always have their respect, foreign service professionals have a general concern when a political appointee is named. But political appointees can be exceptional diplomats—well qualified, highly motivated. Often they can accomplish things because of their access to people a career foreign service officer might not be able to reach.”

Indeed, in addition to other political activism such as serving four times as delegate to the Democratic National Convention from California, Tsakopoulos Kounalakis has meditated with the Dalai Lama and been honored by the Greek Orthodox Church for her interfaith work mediating forums with the World Council of Religions for Peace. She has also served on the California State World Trade Commission.

As president of Sacramento-based AKT Development, however, she was not immune to controversy. Shortly before her confirmation hearings she was engaged in a contentious dispute over the value AKT placed on land sold to a school district. Sacramento’s Natomas Unified School District brought suit against AKT, and the case is still in litigation. Previously AKT had appealed a federal ruling against it involving violation of the Clean Water Act all the way to the Supreme Court. There a 4-4 tie resulted (the lower court’s ruling against AKT was upheld) after family friend Justice Anthony Kennedy recused himself.

Tsakopoulos Kounalakis deems land development the world’s oldest profession, she says, because “people have fought over land since the beginning of time. My life as a businesswoman had a lot to do with negotiation.”

That’s a skill much needed in her current job. A nation of 10 million people where memories of territorial disputes can still lead to international brouhahas, Hungary borders seven countries, from Austria to Ukraine. The nation’s boundaries convulsed in the turmoil of 20th-century Europe. “You cannot look at any system here, any way of thinking, and find an absolute equivalent anywhere else in the world,” Tsakopoulos Kounalakis says, citing the uniqueness of the Hungarian language and complicated recent history.

Imagine a capital city of 2 million people, the home of Europe’s largest synagogue, in a country that lost nearly half a million Jewish citizens only a few generations ago. To a culture that has the shadow of the Holocaust stretching over the Danube, the State Department has dispatched a person who believes the role of religion and faith in people’s lives is still underestimated.

“An interfaith forum,” Tsakopoulos Kounalakis says when describing her work with the World Council of Religions for Peace, “is an incredibly powerful venue for understanding how people think—a close-up opportunity to talk to people who believe completely different things from one another and have more than a bilateral conversation.” She’s fascinated that religious leaders are “raised to positions of power based on their unwillingness to give an inch.” When Tsakopoulos Kounalakis describes her interfaith work, she could easily be explaining politics, weaving seamless connections between the strands of her life.

The political connections that resulted in her appointment as ambassador have their roots in the many times her politically active father, Angelo, involved her in events he organized after Tsakopoulos Kounalakis returned home from Dartmouth via Greece, where she spent some time after graduation. Once back on the West Coast she earned a 1992 M.B.A. from Berkeley and then joined the family business.

Tsakopoulos Kounalakis’ arrival in Hungary overlapped the run-up to national elections in April—a backdrop every bit as tumultuous as the American political landscape. They resulted in the return of former prime minister Viktor Orban. His face is a familiar one—not only because he was prime minister from 1998 to 2002, but because in the pivotal summer of 1989, as Tsakopoulos Kounalakis was graduating from college, Orban took center stage in Budapest by delivering a speech in Heroes Square demanding that the USSR withdraw its troops and allow free elections.

The recent elections were Hungary’s sixth since the collapse of the USSR, and their outcome demonstrated the same desire for change reflected in pre-election polling. A survey conducted in the fall of 2009 by the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project found more than two-thirds of Hungarians were dissatisfied with the functioning of their democracy, and an even higher number indicated the country was on the wrong track.

In a defeat of the Socialists, who had been governing for eight years, the conservative Fidesz (Alliance of Young Democrats) party captured enough seats to have a supermajority in the next parliament and put Orban back in power, but the nationalist Jobbik (Movement for a Better Hungary) party more than doubled its returns of the previous election cycle, as did the liberal, green Lehet Mas A Politica (Politics Can Be Different) party.

Tsakopoulos Kounalakis knows what it is to experience political upheaval. She marvels that she is representing the United States under its first African-American president. “Just when you think the United States has taken a turn for the worse, the voters do something bold and different,” she says.

In many ways Tsakopoulos Kounalakis, an immigrant’s daughter, embodies the American dream. High school in Sacramento, however, did not prepare her for the intensity of an Ivy League classroom. She found herself in archaeology classes with peers who had “studied ancient Greek and Latin at Groton for years,” and she found it “mind-blowing.” Professor Jeremy Rutter “gave me the wake-up call of my life—and it didn’t feel good,” she recalls. “It wasn’t that I was inspired in an uplifting way by his words. I was made to feel that I was tremendously privileged to be there and to ask myself if I was going to make something of it.”

She looks back at her time in college as “a very quiet, focused academic life,” distinct from her youth in California and all that has followed. “For the first time I felt different,” she says. “I felt that I was, that my family was, new to the United States.” That sense of being something of an outsider on an historic campus was underscored when 20 members of her extended family, including her octogenarian grandfather, arrived in Hanover from California for her graduation. Unprepared for New Hampshire’s cold New England June, they embarrassed Tsakopoulos Kounalakis by wearing hastily purchased Dartmouth sweatshirts to the ceremony.

As a student Tsakopoulos Kounalakis spent nights watching TV in Robinson Hall. Her social life, she confesses, was terrible. She focused on studying and working on The Dartmouth. Her father sent her a dozen roses when she became the arts and leisure editor, a job nobody else wanted. For Tsakopoulos Kounalakis being named to the position was more than a thrill—it was the proudest moment of her life. Two decades later she recalls the satisfaction of overhearing students in the Hop chat about how much the arts section had improved. The engraved glass mug every editor receives is among the items she carried to Budapest. She decided not to pursue journalism, she says, for fear she’d “end up in South Carolina doing the police beat.”

Tsakopoulos Kounalakis makes no secret of relationships she’s cultivated since with many of Washington’s most powerful Democratic women including Secretary Clinton, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, California Senators Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, fellow Greek-American Olympia Snowe (R-ME) and Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), whose campaign Tsakopoulos Kounalakis supported from the West Coast. She’s spent hours on Pelosi’s living room sofa, she says, listening to the speaker’s stories and sharing her own. The last thing Tsakopoulos Kounalakis did before leaving California was have dinner with Feinstein.

The ambassador considers herself lucky to have these female role models. The concept of women helping women is her explanation of why so many of them showed up for her confirmation hearing—even after she protested that too many people would speak on her behalf and she didn’t want to take up everyone’s time.

At the swearing-in following her confirmation, Tsakopoulos Kounalakis’ father held the Bible on which she took her oath from Clinton, while Pelosi and Justice Kennedy stood by.

In her Szabadsag Ter (Freedom Square) office before hosting a reading for embassy women of a memoir about motherhood, Tsakopoulos Kounalakis, mother of sons Neo, 9, and Eon, 8, reflects on balancing career and family. “I can do this job, and I can still be there for my kids at night,” she says. “I don’t have to go to every single function if it’s going to harm my ability to parent,” she says. But she can’t do it all. This year their father was the first to meet their teachers, she says.

As a newcomer to Budapest Tsakopoulos Kounalakis is excited about the opportunities her diplomacy will provide her to make a difference. “I can honestly tell you there is a general lack of true understanding of what the U.S. State Department does,” she says. “What you learn very quickly is that we really are the good guys.” Careful to explain she does not refer to Hungary, but to the Eastern Europe region and the networks of U.S. missions around the world, she highlights the work of preventing human trafficking, cracking down on corruption and “stopping the unlawful flow of money that supports terrorist activities or unlawful business activities.” Diplomacy is also about affirmation, she says. Last winter the ambassador presented a Hungarian judge with the International Women of Courage Award to honor her advocacy for victims of domestic violence.

The English major is lyrical about America’s “remarkable capacity to change and renew and grow.” But if a journey from West Coast to East and back, and from West Coast to Eastern Europe is any indicator, the description also fits an individual who fuses business savvy with a zest for intercultural dialogue. Perhaps there is a kernel of the once-shy outsider left in her. She hasn’t returned her annual Green Card update to the College in years, she says, wondering what she would have to say.

Cynthia Marie O’Brien, a former DAM intern, teaches writing at Manchester (Connecticut) Community College.