It began nearly a century and a half ago in front of a handful of people curious about the way an oddly shaped inflated sphere bounced on a desolate Massachusetts field. In that long-ago moment, a ragged band of Dartmouth students, fired more with passion than proficiency, engaged in the College’s first football game with Harvard. It did not go well. The 53-0 defeat prompted The Dartmouth to produce an editorial declaring that football was dead at Dartmouth.

“There was no doubt, no mystery about its death, and an inquest is totally unnecessary,” wrote the editorial board following the 1882 debacle, “and now if there is any other game that Dartmouth can play better than foot-ball, it would be well to encourage it.”

For reasons now unknown, Dartmouth footballers ignored this sage advice and eventually thrived well enough to win a national championship in 1925. Twelve years later, they were asked to play in the 1937 Rose Bowl, only to decline the invitation in favor of letting players prepare for finals. From there, they rose to moments of Eastern football supremacy, winning the Lambert Trophy in 1965 and 1970.

And, yet, despite all of Dartmouth’s gridiron glories during the last 143 years, there is one constant, one game that annually rises above them all. Deep in the green soul of Dartmouth students and alumni, beating Harvard always provides the sweetest football moment of all, no matter the season, no matter the venue. Perhaps no game in Dartmouth history was more satisfying than 1964’s triumphal 48-0 thumping of Harvard, a game made even more glorious because the victory was televised by NBC.

Every true Dartmouth fan knows exactly how many times the Big Green has defeated the Crimson—48—even if they’re a little hazy on how often Harvard has prevailed (74).

Through good times and bad, wartime and peace, this epic rivalry has been rejoined annually, both sides practically frothing with anticipation as the big day approaches.

Until maybe this year.

The November 1 game at Cambridge will be played at a juncture like none since the rivalry began. It comes amid the national crisis swamping higher education, with Harvard as “Ground Zero” in the struggle over who controls university life, college admissions decisions, and classroom course content.

(Game preview: “Undefeated Harvard Slight Favorite in Dartmouth Showdown”)

Far from Harvard Stadium, the university is battling for its federal grants, fighting for its freedom to select students and teach without interference from Washington, D.C., while struggling to retain its identity as the premier research institution on the planet. Dartmouth has so far been spared the deep funding cuts and threats from the federal government, but the College has made clear that it stands with Harvard, filing a brief in support of the university’s lawsuit to restore its research funding.

Dartmouth people do not dispute Harvard’s preeminence as a research university and do not aim to match it. We Hanoverians are loyalists of a small, primarily undergraduate college surrounded by mountains and forest, and we tend to our own up here. But many of us cheer Harvard in its legal fights like a brother.

“I admire everything Harvard is doing to withstand this egregious overreach by Washington,” says Reggie Williams ’76, who played on two Cincinnati Bengals Super Bowl teams and appeared on the cover of the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine manhandling Harvard’s Pat McInally, who eventually became his Bengals teammate. “If that is their cause, I may give them a clap or two.”

But some Dartmouth alums believe Harvard is getting what it deserves—and this perhaps makes them want to beat the Crimson even more.

“I’m sympathetic with the taking of a serious look at Harvard’s toleration of antisemitic actions against students,” says Scott Johnson ’73, one of three Dartmouth alumni who founded the conservative Power Line blog. “I’m happy about the intervention.”

Either way, after a rivalry that has spanned a century and a half, the competitive spirit may be coded into the genes of these two teams. This year, the game means more than ever. For the first time, Harvard and Dartmouth may be playing for a slot in the national college football playoffs: The champion of the Ivy League gets an automatic berth. Whatever sympathy Dartmouth fans harbor for Harvard’s political plight, crushing the Crimson on the gridiron could well taste sweeter than ever.

It was a match of good versus evil, a clash of civilizations, though in truth only the Hanoverian partisans possessed the attributes of a civilization while their rivals practiced a way of life—snooty, vulgar, arrogant, in all ways offensive—that defied every definition of civility.”

—S. Stanford Phinch, mythical Dartmouth alumnus, in one of his annual essays in the Harvard-Dartmouth football program

For decades, long before the Ivy League was eclipsed by the rise of Power Four semi-professional college teams, its football had a special, even gilded, status; its game stories appearing in eight-column headlines on the front of The New York Times sports section; its whiskey sour- and Bloody Mary-infused tailgates predating the pregame rituals at college football games across the country.

All that time—except for a single occasion, a 14-9 victory in 1955—the game was played in Boston, providing the staid, buttoned-down old town with a gaudy, rowdy spectacle as the men of Dartmouth, wave on wave, poured into the city. As a lewd version of the beloved anthem “Dartmouth’s in Town Again” put it: “Run, girls, run.” There were raucous parties, sometimes around Soldiers Field Road, sometimes in ballrooms at established downtown hostelries such as the Parker House.

One year, the administrators of Simmons College cautioned their female students to avoid the Dartmouth men as if they carried a deadly bacillus from a particularly disfavored, fever-ridden island. One year, the dutiful factotums of Wellesley College, fearing mayhem and the wanton destruction of property, sent out a similar warning. Another year, a marauding band of Dartmouth students was seen on the Friday before the Harvard game wandering the campus of Endicott Junior College in Beverly, Massachusetts, 40 minutes from Cambridge. Someone had told them it was a women’s school.

Meanwhile, as Harvard and Dartmouth squared off each fall, the rest of eastern Massachusetts went about its business.

“We knew there was a lot of racket over there in Cambridge,” says Sol Gittleman, who began teaching at Tufts University—devoutly Division III in athletics—in nearby Medford in 1964 and eventually became the university provost. “But for us at Tufts, it was as if the ruckus was in a foreign country.”

That was then.

In 1974, Dartmouth President John Kemeny, who had already shaken up Dartmouth by presiding over the admission of women and converting the College to a year-round academic schedule, came up with the revolutionary notion of letting Dartmouth play host every other game. He said it was high time Harvard students saw what a college looked like.

Why did any of this matter? Perhaps a Notre Dame alumnus has an explanation.

“Since most college-football programs have no real shot of ever winning a national championship, success has to be defined by achievable goals … and, above all, beating your nemeses,” wrote Steve Larkin, the managing editor of the Washington Review of Books, adding, as an example, how “the two sides of Pitt and West Virginia are (in the opinion of the other) effete and out-of-touch city dwellers and inbred hillbillies with bad dentistry.”

The annual trip to Cambridge provided Dartmouth with a priceless opportunity for exposure, however briefly, to some of the essentials of civilization as well as a useful, if painful, lesson in the intricacies of the game which Harvard had devised and perfected.”

—J. Bennington Peers, mythical Harvard alumnus, in one of his annual essays in the Harvard-Dartmouth football program

The cultural clash of Pitt-West Virginia is replicated here in New England. Here, the Harvard-Dartmouth game is a clash of values, viewed in our precincts as the collision of the sophistication and the self-conscious refinement of the Harvards against the rural rough-and-ready and ruddiness of the Dartmouths. Perhaps it matters because Harvard and Dartmouth alumni have always thought of each other the way prominent intellectual Samuel Johnson thought of Catholics: “In everything in which they differ from us, they are wrong.”

Or, as the estimable Alfred Duclos, who a half-century ago solemnly distributed gray athletic wear and wisdom from the depths of Davis Varsity House, put it to almost every freshman football player, “You’re not big enough to play at Dartmouth … go down to Harvard.”

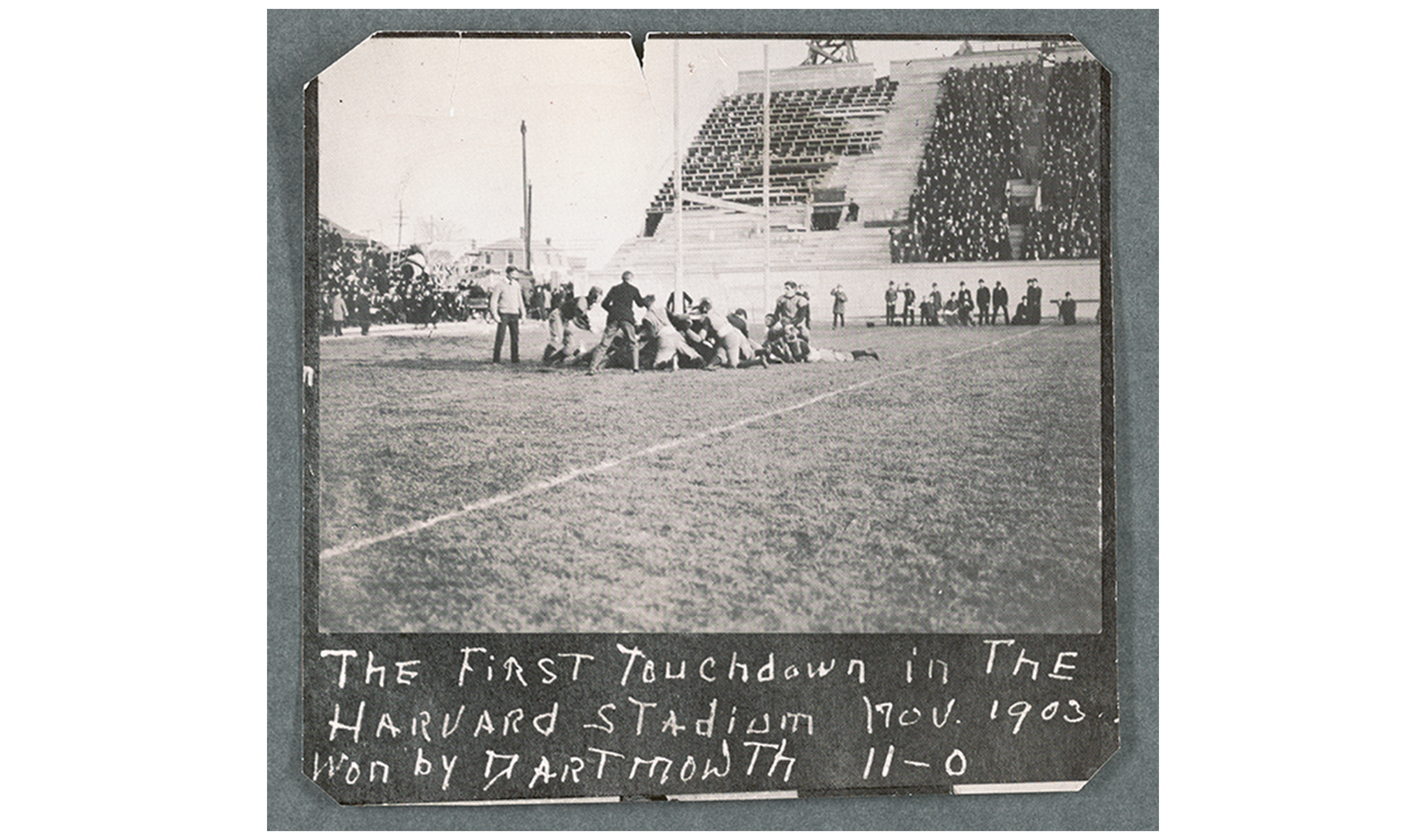

This rivalry has produced some of the greatest moments in the annals of New England sport: There is Dartmouth scoring the first touchdown in the new Harvard Stadium in 1903. There is Charley Brickley’s drop kick to win the 1912 game for Harvard, 3-0; Barry Wood’s last-minute 48-yard touchdown pass to Carl Hageman and then Wood’s point-after to beat Dartmouth in 1931, throwing the stadium into an uproar, as the Times put it. And who can forget Dick Clasby’s performances in Harvard’s 1952 and 1953 wins or Bill Beagle’s sparkling play in Dartmouth’s 1954 and 1955 wins?

Few Dartmouth performances were more memorable than tailback Shon Page’s 222 yards rushing in 23 carries to pace a 17-0 domination of the Crimson in 1990. But, 13 years later, Andrew Hall’s memorable catch came close, sparking a fourth-quarter rally and Dartmouth victory that would be the Green’s last over the Crimson for more than a decade.

Jack Manning ’72, a cornerback whose Dartmouth teams won the Ivy League championship every year he was there, recalls how Coach Jake Crouthamel ’60 was especially revved for the annual tilt at Cambridge.

“Jake would start the Harvard week by softly telling us how important beating Harvard was, and then his talks would get fiercer and fiercer, louder and louder, as the week went on,” Manning says. “We loved playing on the road at Harvard and that made those victories in their great stadium even sweeter.”

Carol Crouthamel, the coach’s widow, recalls how “Harvard was a tough week, even in years when the Princeton game was more important.” It galled the Dartmouth coach that his record against Harvard was 2-4-1, though all but one of the losses were by seven points or less.

That intensity had its version in Cambridge. “You never needed to give a Knute Rockne pep talk for the Dartmouth game,” said John Yovicsin, who coached the Crimson between 1957 and 1970. “The team had themselves sky-high and sometimes they had to be held in check. There was no lack of self-motivation.”

Mike Lynch, Harvard ’77, who in 1976 kicked a field goal late in the Crimson’s 17-10 victory at Memorial Field, can attest to that. “The Yale rivalry is supposed to be the big game for us at Harvard, but Dartmouth was always the litmus test,” says Lynch, who later became a top sportscaster at Boston’s WCVB television station. “They had quality teams, quality coaching, and there was always the invasion from Hanover and 42,000 people in the stands. Somehow, they got under our skin.”

When Cole Porter, Yale class of 1913, wrote “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” in 1936—the year of a 26-7 Dartmouth victory over Harvard—his lyrics included:

I’ve got you under my skin

I’ve got you deep in the heart of me

So deep in my heart that you’re really a part of me.

That speaks to the vanity of small differences that, from afar, separate these two institutions—for really, do Harvard and Dartmouth seem so very different? But up close in New England, on Saturday afternoons in the autumn, those small differences seem big indeed. That’s especially so when, as Richard Hovey, Dartmouth 1885, wrote in the “Hanover Winter Song,” the wolf wind is whining in the doorways,/And the snow drifts deep along the road.

The clash of civilizations may be a bit muted this year amid the broader controversy about who controls universities in the United States and whether Harvard can remain “a tub on its own bottom,” to borrow a Cantabrigian phrase.

Some Dartmouth alums hope the answer is “no” and that the Trump administration continues to take a hard line. “Harvard’s nonprofit status ought to be in jeopardy,” says John Hinderaker ’71, who also graduated from Harvard Law. “They have not begun to internalize the danger their policies and record have put them in.”

Former Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Paul Kirk, Harvard ’60, says Dartmouth seems to be waking up to the danger.

“It took someone to tear the democracy apart to get Dartmouth to see the light,” says Kirk, a former tight end for Harvard whose teams lost twice to Dartmouth. “To this day, I have great respect for Dartmouth football, though not enough to have wanted to go there.”

Despite all the tough talk, there have been plenty of tender, even sweet, moments in this rivalry.

One of them came in October 1962, amid the Cuban Missile Crisis, when, as Paul Kirk’s brother Ed recalled, “A packed stadium turned to the flag and sang ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ as never before.” That was in part an homage to the travails of John F. Kennedy, Harvard ’40, an end on a Crimson junior-varsity team that lost the 1937 JV game to Dartmouth, 20-0. (The Times account of that JV game 88 years ago was many times longer than its story about this year’s varsity game will be.)

Many of those evocative moments came when Tim Murphy and Buddy Teevens ’79 were the coaches of Harvard and Dartmouth, respectively. The two had grown up together; played football together at Silver Lake Regional High School in Kingston, Massachusetts; coached together at Boston University and the University of Maine; was best man at the other’s wedding and godfather to each other’s children; and considered each other their best friend. When Teevens was struck by a F-150 truck in Florida, Murphy drove all night to be with him in the hospital. When Teevens died in 2023, there was no more devastated mourner outside the family of the Dartmouth coach.

“It was different with me and Buddy,” Murphy told me. “When we beat Dartmouth, walking across that field to shake Buddy’s hand, I always felt a little guilt because of our long and close relationship. We were both such competitors, but more importantly we were more like brothers.”

During the course of the past several months, as Harvard’s battle with the federal government has unfolded, I have spoken with countless Dartmouth alums and former football players. To a one, dyed-in-the-green men and women have said they are rooting, rooting hard, for Harvard—except for about three hours on November 1. The sentiment is near universal: Let’s win the game. Let’s hope Harvard wins its larger, more important battle.

Now, a few personal reflections. Growing up in the Boston area as the son of Dick Shribman ’47, I knew of the importance of this gridiron confrontation, always played less than 18 miles from my home. Each year, Alan Epstein ’47 and his wife, Sally, would come from New York and Al Schmidt ’51 and his wife, Joan, would come from New Jersey, and they and my dad and mom would go to that most sacred of all rituals, the Harvard game. I was not permitted to attend one of these events until I was a Dartmouth student myself. The Harvard game was strictly an adult affair.

Later, John Powers, Harvard ’70, and I would engage in the juvenile exercise of excoriating our respective rivals. Now it can be told: J. Bennington Peers is the nom de plume of John Powers, and S. Stanford Phinch is the nom de guerre that I inherited from longtime sports information director Jack DeGange, an adopted ’71, for our diatribes that for years appeared in opposite-facing pages in the Harvard-Dartmouth football program. We had great fun trying to outdo each other in opprobrium, but in truth we became friends and, for a decade when he was the peerless Olympics writer and I the Washington bureau chief, we were colleagues at The Boston Globe.

I caught up with Powers—or, if you prefer, Peers himself—as this year’s gridiron season approached. We had a couple of laughs and reminisced about the games we viewed from opposite sides of Harvard Stadium and, later, Memorial Field.

“Not that it wasn’t enjoyable to poke fun at Yale and its Gothic rockpile,” he says, “but how could one resist lampooning Dartmouth, which had a campfire for a campus? And yet there is no more charming place to watch football. Harvard may have invented the game, but Dartmouth created the mood.”

In truth, the whole thing is a mood, a mixture of passion and mirth.

It prompted Dartmouth for years to halt classes at 12:30 on the Friday before the Harvard game to permit students to get to Cambridge in daylight. It prompted Art LaFrance ’60 and Bob Hatch ’60, Tu’62, to travel to Cambridge before the 1956 game with five gallons of gasoline they used to burn a gigantic “D” on the 50-yard line of Harvard Stadium. It prompted Dartmouth alums to resist the administration’s effort in the 1960s to substitute “Princeton” for “Harvard” in the College’s repertoire of songs or make Princeton Dartmouth’s preeminent rival. The Harvard rivalry was simply too intense to be defanged by cosseted College vice presidents who thought they knew the Dartmouth culture—but didn’t.

Ed Marinaro, Cornell ’72, one of the greatest players in Ivy League history—and one who resisted Crouthamel’s entreaties to enroll at Dartmouth—wonders about the enduring power of the Harvard-Dartmouth rivalry, speculating, “Maybe it was because there was so little to do up there in New Hampshire.” Indeed, generations of Dartmouth students found time to sing a song whose lyrics included the line, “To hell with Harvard.” And, of course, Peers and Phinch found time to engage in the fantasy that someone would actually read their essays vilifying the other’s school.

So, now, Harvard and Dartmouth are together again for The Game at Harvard Stadium.

In the course of the afternoon of November 1, the schools will root against each other as if the game mattered dearly. But by the time the sun sets over the Allston athletic complex, another battle will continue to rage—one that, beyond the playing field, matters even more, wherever you stand on the issues or sit in the stands.

David Shribman, a trustee emeritus of the College, was for 16 years executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. His five books on Dartmouth lore and history include Green Fields of Autumn, a chronicle of Dartmouth football written with Jack DeGange.