No one living remembers that championship season. Its players have all died, as have the tens of thousands of fans in raccoon coats and bowler hats. That season lives on only in yellowed newspaper clips and a remarkable scrapbook in the College archives.

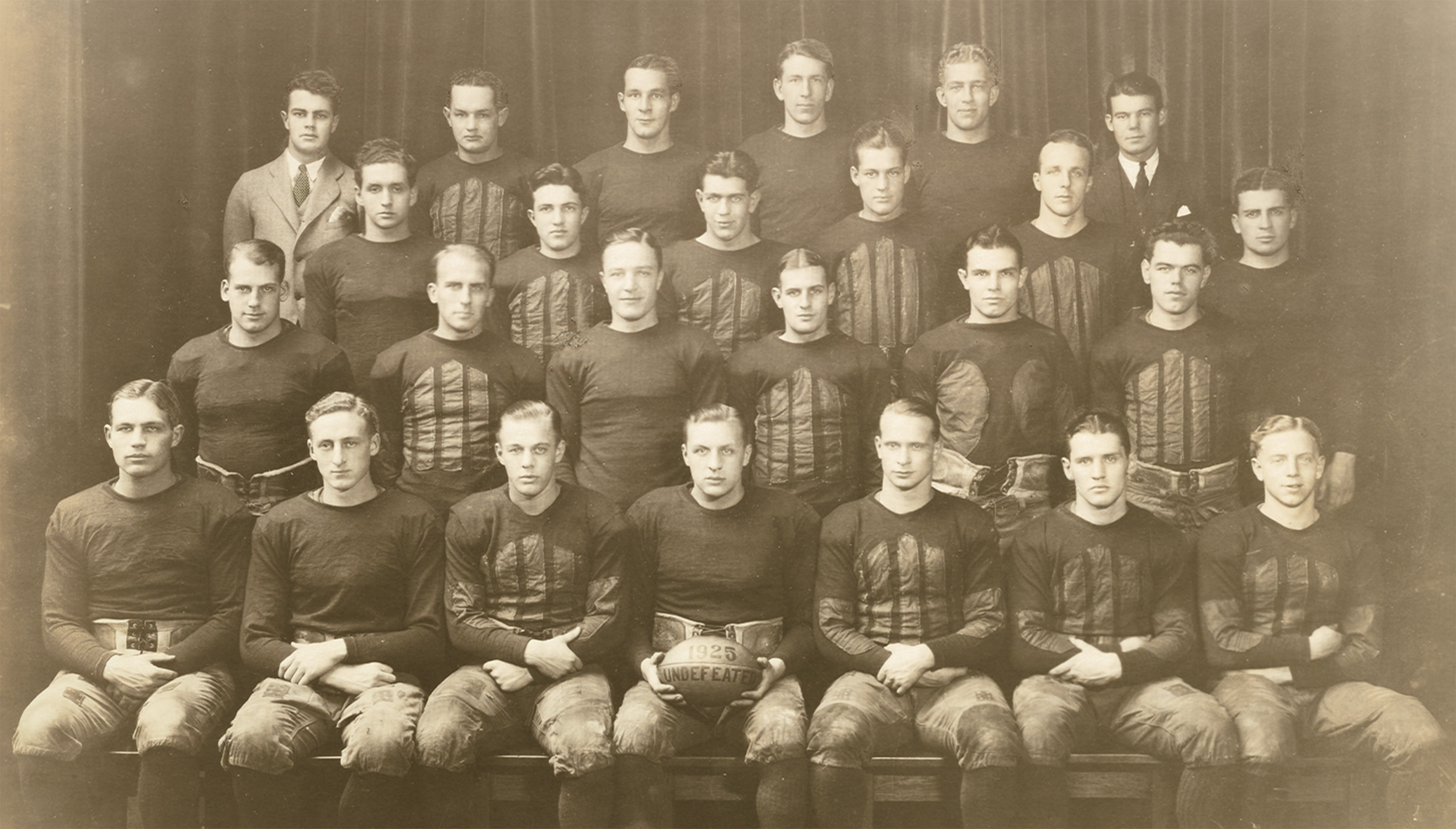

Dartmouth was undefeated in 1925. The Big Green was in the middle of a three-year, 21-0-1 unbeaten streak that began in 1923 with a 16-14 win against Brown and continued until a 14-7 loss at Yale in 1926.

Never again would Dartmouth approach national championship status. The team was invited to the 1937 Rose Bowl game but declined to play, citing the distraction a postseason game would present to student-athletes’ academic performance. The last time the team was nationally ranked was 55 years ago, when it played Yale before a crowd of 60,820 in 1970.

But in 1925—when Vermonter Calvin Coolidge was in the White House, F. Scott Fitzgerald published The Great Gatsby, and Sweet Georgia Brown was the top song—the presence of Dartmouth atop the national football rankings didn’t seem at all incongruous. Hardly anyone cared about the embryonic NFL, then only 6 years old.

The center of gravity of American football was the East Coast colleges. Cornell, Princeton, Harvard, Penn, and Yale also roared to national championships in the 1920s—a supremacy that sounds implausible to modern football fans. “The Great Dartmouth Team Is No Longer” is the title of a chapter on the decline of the prominence of Eastern football in Derek Catsam’s 2021 The History of American College Football. And when The Wall Street Journal wrote about efforts by coach Buddy Teevens ’79 to minimize gridiron injuries five years ago, it titled its piece “Dartmouth Is the Blueprint for NFL Football. Yes, Dartmouth.”

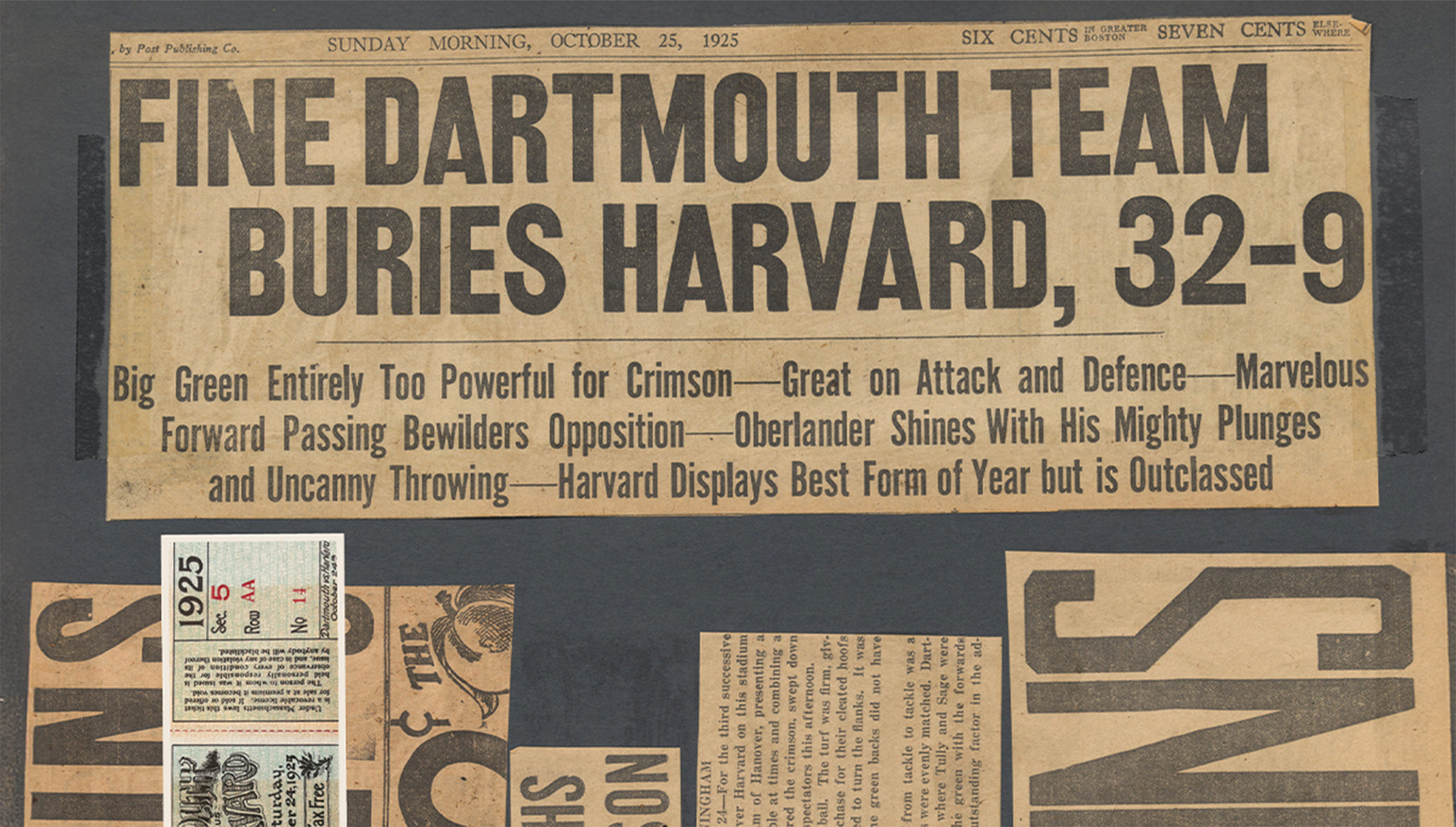

No headline would have smirked like that a century ago, when Dartmouth began the season scoring 199 consecutive unanswered points. No one would have reacted with astonishment at the notion that Andrew “Swede” Oberlander, class of 1926, who had 477 yards of total offense and accounted for eight touchdowns against a powerful Cornell team, would have won the Heisman Trophy—had there been one.

No one would have questioned the primacy of a Dartmouth team that won by an average score of 43-4; a team so dominant that, as the season progressed, it often would decline to accept rivals’ penalties; and a team that prompted the legendary Amos Alonzo Stagg, the Chicago coach who invented the quick kick, the lateral pass, and the quarterback-keeper play, to call it the greatest team he ever saw. And no one would have minimized the offensive power and defensive discipline of a team journalist Damon Runyon said was “champion of the world.”

Or at least champion of the world of sports. Headed by coach Jesse Hawley, class of 1909, the 1925 Dartmouth team had only three rivals nationally: Michigan and Pitt, which each finished with a single loss but played more demanding schedules; and Alabama, which finished with a 10-0 record and took the Rose Bowl invitation Dartmouth declined.

“But for a season’s record, the showing made by Dartmouth leaves a green flag waving above them all,” Grantland Rice wrote, adding, “We can recall no attack in modern history that has piled up as many points in feature contests and has shown so much versatility and as much power and speed.”

Who were these leather-helmeted warriors? One of them got his nickname from a poem. Another won a Rhodes scholarship. A third played for the Boston Bruins and was inducted into both the hockey and the college football halls of fame before joining the legal team that prosecuted the Rosenbergs for passing nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union.

Together they inspired a booklet on how success in football led to success in business. Titled What the 1925 Football Season Taught Us About Big Organizations, it came with an introduction by E.K. Hall, class of 1892, captain of Dartmouth’s 1891 team, vice president of the American Telephone & Telegraph Co., and chairman of the collegiate football rules committee. In that publication, the players said, “Fairness was one of the elements which made for our football success. The football organization with autocratic principles is no longer the predominant type, any more than is the autocratic business organization.”

Those players began preseason training bunking in Alumni Gymnasium. Coaches slept in cots above Allen’s Drug Store on Main Street, where in the evenings they conjured imaginative plays scratched on paper and tacked onto a cracked plaster wall. If accommodations were rudimentary, the team’s game-day meals were extraordinary, heavy on beef for lunch and dinner, with prunes and Cream of Wheat and broiled lamb chops for breakfast.

These men were led by a remarkable coach. Hawley, who won a Big Ten gymnastics title at the University of Minnesota before transferring to Dartmouth, was a gifted football halfback and a champion discus thrower. Hired after graduation as head football coach at the University of Iowa, he was known as an innovator, harsh taskmaster, and rigid adherent to minute details in practice sessions—a style subsequent Big Green coaches such as Bob Blackman would retain and refine. When he retired from coaching in 1928, his record at Dartmouth stood at 39-10-1.

At Dartmouth Hawley assembled an exceptional group of student-athletes who would dominate Eastern football. His 1924 team, which had five shutouts en route to a 7-0-1 season, had a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society on either the first or second team of every position. Hawley was, according to the Aegis, “the prime mover in the installing of the element of psychology into modern football.”

The brightest star in the Dartmouth firmament in 1925 was Oberlander, who earned the moniker “Swede” because he timed his passes to Henry Sage, class of 1926, to the rhythm of the opening line of a poem that he said began: “Ten thousand Swedes jumped out of the weeds at the Battle of Copenhagen.” His fingerprints were on every touchdown but one in Dartmouth’s 62-13 rout of Cornell. His six TD passes in that game remain a record approached only by Jay Fiedler ’94, who had five against Penn in 1992. Overall, Oberlander had 14 TD passes in eight games.

Then there was Myles Lane, class of 1928, who went on to play for the NHL after graduation and later served as a New York Supreme Court justice. As a sophomore, he had three TD receptions against Cornell and Chicago and was the team’s scoring leader with 102 points. He was the national scoring leader as a senior, and his 18 TD receptions stood for a time as a Dartmouth record.

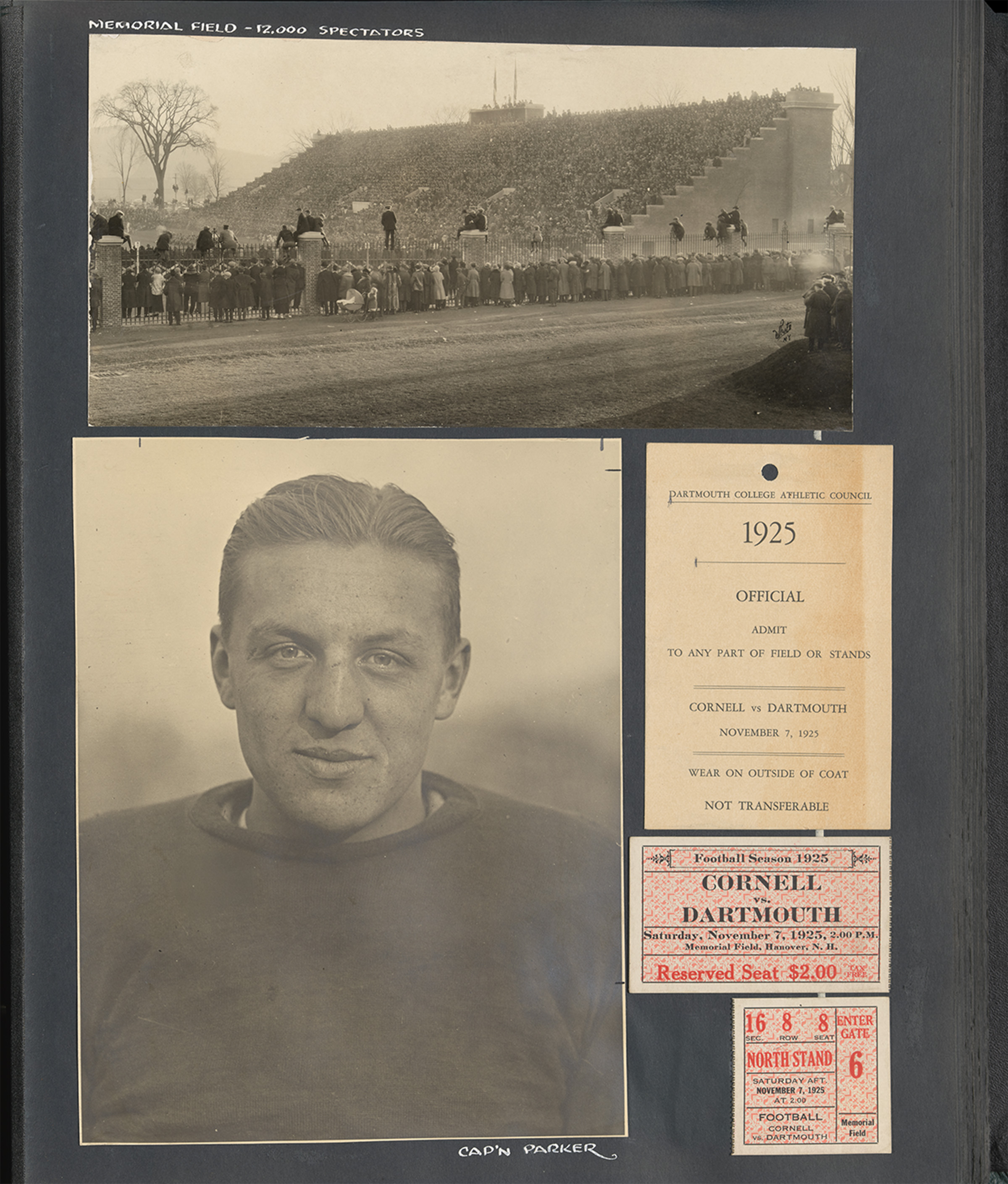

Captain Nate Parker, class of 1926, later founded a Pittsburgh brokerage firm and was a member of the New York Stock Exchange. As a senior he wrote, “It may be reassuring to prospective business men, or perhaps their fathers, to learn that the hours spent on the football field have not been wasted but devoted to something with principles of practical application.”

Other standouts included Carl “Dutch” Diehl, class of 1926, ranked at the time as the greatest guard in Dartmouth history. George Tully, class of 1926, caught seven TD passes and kicked 26 extra points in the championship season. Diehl was so overwhelming a presence that sportswriter Stanley Woodward—widely regarded as the inventor of the term “Ivy League”—predicted that the words “Oberlander-to-Tully” mighty someday replace “Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance,” the fabled phrase about the Chicago Cubs double-play combination from a 1910 baseball poem by Franklin P. Adams. Along with Oberlander, Parker, and Diehl, Tully was named a football All-American that season.

And one more: Del Worthington, class of 1926, the team’s senior manager. He never played a down. He never flubbed a task. His job included bribing theater comedians to insert players’ names into their jokes and distributing game tickets to politicos and police officers. But his greatest contribution was a 142-page, two-volume set of scrapbooks that offers what he called “a manager’s eye view of some of the things that went on behind the scenes.” Now in the College archives, they provide a textured view of the time and team that won recognition that even the undefeated Big Green of 1970, perhaps Dartmouth’s most powerful squad, was unable to match.

It isn’t only the football in that century-ago era that grabs our attention today. It’s the spectacle of it all—the hoopla and the hype, the dances and the direct-wire telegraph connections that allowed alumni in Los Angeles and Spokane, Washington, to follow each play—that stands out.

The October 24 Harvard game attracted 54,000 fans, and administrators at Dartmouth and Harvard swore they could have sold at least 30,000 more tickets. The resulting convergence of 20,000 automobiles around Harvard Stadium prompted a reporter to write, “Never in the history of local gridiron struggles was there such a jam of motor vehicles of all sizes and descriptions from all over New England and elsewhere.” Some 150 extra police officers were deployed to the scene. More than a half-million dollars was wagered on the game—the equivalent of more than $9 million in 2025. The Boston Herald’s Neal O’Hara wrote that “the usual jackass was loose at the football game, careening around in an airplane over the crowded stands.”

When it ended with Dartmouth’s triumph, a dozen of what Boston Globe sportswriter Roger Birtwell called “big sturdy patrolmen” were dispatched to the field to protect the goal posts from “the wild-eyed New Hampshire mob” determined to tear them down in pure joy. “Finally, after an hour of riotous celebration,” he wrote, “the adherents of Dartmouth’s green-clad grenadiers departed from the stadium to spend the evening in continued celebration.”

That evening the two teams held the Intercollegiate Ball in the grand ballroom of the Copley Plaza hotel. The advertisement for the event bellowed: “Everybody’ll be there.” Well, not quite everybody: Administrators from five colleges, including Radcliffe and Wellesley, banned their students from attending. Simmons officials were aghast at hints of cigarette smoking and the presence of liquor-filled flasks, verboten in the fifth year of Prohibition.

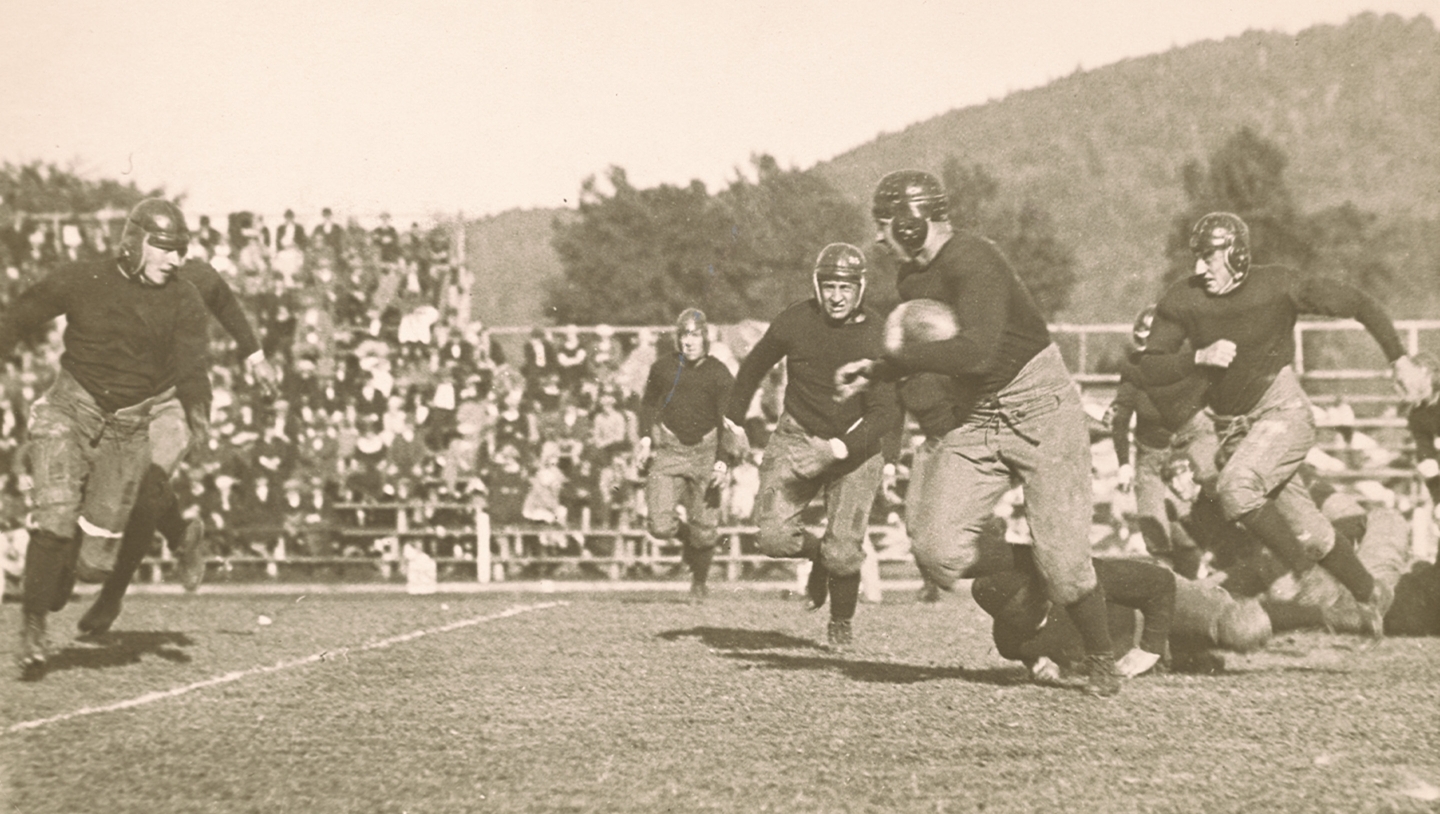

Dartmouth’s team marched through its schedule, mowing down Norwich (59-0), Hobart (34-0), Vermont (50-0), and Maine (56-0) before felling Harvard (32-9) and Brown (14-0). Then came Cornell, which had defeated St. Bonaventure 56-0, downed Susquehanna 91-0, and strode undefeated onto Memorial Field after having outscored its opponents 212-to-14. No contest: A record home crowd saw the Green unleash a 62-13 attack that sportswriter Rice said “would have broken the Hindenburg line and swept any rival air fleet from the sky.”

One obstacle remained: an intersectional game at the University of Chicago that would seal Dartmouth’s aspirations for national dominance.

The team set out by train to Montreal and held a practice in Flint, Michigan, before arriving in Chicago, where so many Dartmouth alumni were assembled that the strains of “Dartmouth’s in Town Again” were heard in the Loop. Damon Runyon noted that “old grads of Dartmouth” were “inaugurating a period of old-gradding such has never been known before in the United States of America.” They were joined by 90 sportswriters who arrived to cover the confrontation.

Dartmouth’s 33-7 victory over Chicago was the most severe thrashing a Maroons team had suffered since its 49-0 loss to Minnesota nine years earlier. The analysis from a disappointed Chicago player: “Our running game was undoubtedly superior, but our defensive playing against your forward passing was dumb.”

Rose Bowl and Orange Bowl invitations followed. Both were declined. “Our season is over,” said Hawley. “When it’s over, it’s over. We play no post-season games.”

Days later, after a postgame ball at Chicago’s Congress Hotel, the team returned to Hanover.

“All Dartmouth College—students, faculty, and the citizens of this hill town—turned out tonight just before midnight to welcome home their great undefeated football team from its sweeping victory at Chicago,” Burton Whitman wrote in the Boston Herald. It was a celebration “present undergraduates will talk about to their children’s children.”

One hundred years later, the remarkable story of the 1925 national championship team is enough to enthrall the children of those children’s children.

David Shribman won the Pulitzer Prize in 1995 and edited the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette from 2003 to 2018.