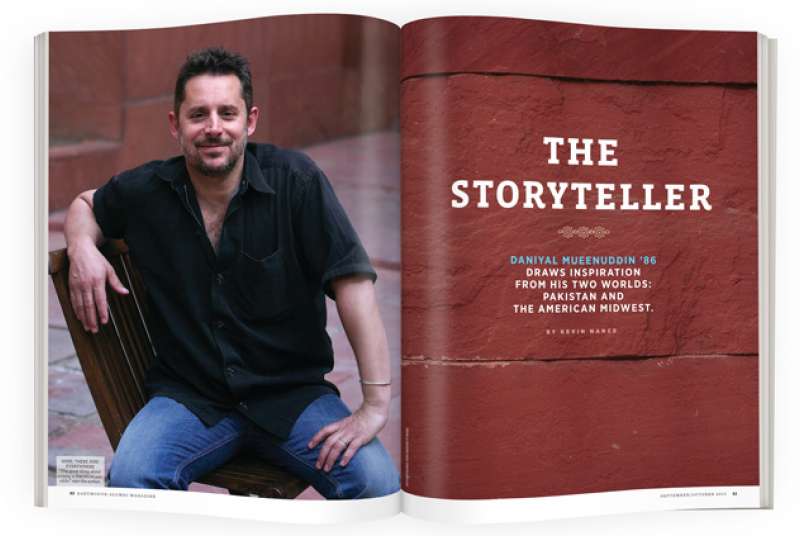

The Storyteller

“You’re going to kill me,” Daniyal Mueenuddin joked to his literary agent not long ago. “I’m writing a book set in America.”

Perhaps he was only half-joking. Mueenuddin, after all, is best known as the author of In Other Rooms, Other Wonders (W.W. Norton, 2009), an acclaimed collection of linked short stories set in the mid-20th century on a farm in rural Pakistan, where he was raised. A finalist for the National Book Award, the volume earned its author comparisons to Chekhov and a devoted following of readers enchanted by its portrait of a crumbling feudal society with its elaborate hierarchies and network of carefully calibrated, often fiercely competitive relationships among the farm’s workers and their families. It remains to be seen how readers will react to Mueenuddin’s recently completed and yet to be published first novel, I. Want. You. To., which is set in Wisconsin and New York City from the 1980s to the present. The novel—its title is a phrase from Chapter 11 of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which Mueenuddin discovered at Dartmouth and which maintains for him the status of holy writ—is the story of Kristal Slama, a smart, beautiful young woman with working-class roots in Black Earth, Wisconsin. “She’s from the kind of people who have lots of abandoned cars in the yard,” the author explains, “and tied-up dogs who aren’t fed properly.” But Kristal’s life is transformed, for better and worse, when she’s taken under the wing of a worldly couple in Madison and later becomes a graduate student in Manhattan. There she finds material success and heartbreak as the wife of a wealthy lawyer. Conspicuously for Mueenuddin’s fans, the novel has, as he puts it succinctly on a balmy recent afternoon in Madison, “nothing to do with Pakistan.”

This is a concern, of course, for various reasons. Will his American readers follow him from South Punjab to central Wisconsin? And will they find its portrait of a world much like our own as beguiling as the far more unfamiliar territory of Pakistan? “People have said to me about my last book, ‘The reason it was successful was that you’re writing about this exotic, distant place,’ ” he says with a touch of pique. “If this book turns out well, that criticism will be stilled.”

Not to worry, Bill Clegg, Mueenuddin’s literary agent, told him in response to his joke: “Write what you want to write, and there will be a different audience.” Now Clegg says, “As Daniyal’s stories have been compared just as frequently, perhaps even more, to the work of Turgenev, Chekhov and Alice Munro than that of other Indian or Pakistani writers, it’s clear that it’s his excavation of how people happen within the particular economies of class and gender, town and country, that engages readers more than his transcription of place. That said, it’s no secret that the divergent backdrops of Daniyal’s life have greatly informed and inspired his work.”

It’s true. The setting and many of the characters of In Other Rooms, Other Wonders were based on the actual farm on the southern plains of Pakistan where Los Angeles-born Mueenuddin largely grew up and which he inherited from his late father, Ghulam Mueenuddin, a leading Pakistani civil servant and diplomat. The author declines to reveal just how large the farm is—“In Pakistan,” he says, “it’s best not to talk about how much land you have, for political reasons”—but he oversees a vast operation, growing hundreds of acres of mangoes, sugar cane, cotton, rice, wheat and greenhouse vegetables, and employing an army of workers and operating a school for their children. In I. Want. You. To., on the other hand, fictional Black Earth closely resembles Elroy, Wisconsin, two hours from Madison by car, where Mueenuddin, 51, still spends time on the 645-acre farm he inherited from his American mother, Barbara, a fiction writer and former society columnist for The Washington Post.

Mueenuddin and his Norwegian-born wife, Cecilie, spent the summer in a rented house in Madison, where she was enrolled in an intensive course in Urdu, which her husband speaks when in Pakistan. The Mueenuddins are moving this fall to England, where Cecilie, an anthropologist, will be pursuing a graduate degree at Oxford University; her husband will commute by air to Pakistan every two months or so to keep an eye on the farm. “The great thing about writing,” he says with a smile, “is that it’s so portable.”

And so I. Want. You. To. is an exploration of Mueenuddin’s Wisconsin heritage and history, which is just as important to his makeup, in its different way, as Pakistan. He loves spending time on the farm in Elroy, which he rents to a local Amish man who raises buffalo on the property, tending the land with the help of a team of horses and 15 sons. “I asked him to put a new roof on the barn once,” Mueenuddin recalls. “A few days later this army of strapping boys shows up to do the work. It was like a swarm of locusts.” In Elroy, Mueenuddin’s normally Pakistani-inflected English quickly shades into the local parlance and its flat, folksy Midwestern accent. “Come on, man,” he’s known for saying to his neighbors, “wanna beer?” “The thing I love about the farm in Elroy is that it feels safe,” he says now. “I know I’ll never lose that, as long as I take care of business. The farm in Pakistan, on the other hand, is always at risk. It’s very hard, very exhausting being there. And yet it’s where I’ve spent most of my life and I know that land perfectly. They’re so different, the two places, that I’m not sure I can even say which I’m more at home in. It’s like choosing among your children—you can’t really do it.”

Although the two places are radically dissimilar, they meet and blend in the person and writing of Mueenuddin—so much so that, in his wife’s view, readers of I. Want. You. To. won’t find it so different, after all, from his earlier work. “It’s still very him,” says Cecilie, who met her husband while he was a Fulbright scholar at the University of Oslo. “It doesn’t feel like a complete departure from what he’s done before. The setting is different from Pakistan, but people’s lives contain similar kinds of drama wherever you are—relationships, money, jobs, children. People are similar in the way they deal with these kinds of things, and that’s what Daniyal is writing about.”

Mueenuddin’s path to a career in literature was decidedly circuitous. Although he grew up as the child of parents with literary leanings—his mother wrote literary fiction, winning two Pushcart Prizes, and his father often recited Urdu poetry and even wrote some himself—Mueenuddin was never entirely convinced of his own potential as a writer, perhaps in part because of his father’s skepticism. “Darling,” Ghulam Mueenuddin once told his son, “you should know that six generations of your family have written poetry—all of them badly.” Nonetheless, young Daniyal wrote poetry, even if most of it continued the family tradition of mediocrity. His mother encouraged him to persist, and by his Dartmouth years he had decided to pursue literature, spending long hours in Baker Library reading the moderns—Joyce, Woolf, Stein, Kafka and Mann in fiction, Berryman, Lowell, Randall Jarrell, Constantine Cavafy and James Merrill in poetry—with an eye toward following in their footsteps. “I was the ultimate geek,” Mueenuddin recalls with a smile. “I spent so much time in the stacks that the librarians became concerned about me. One of the librarians tried to set me up with his daughter because he thought I needed a social life.”

Easily the most formative aspect of his life in college was a course in Joyce, with an emphasis on Ulysses, taught by Peter Bien, who became perhaps the most important mentor of his life. “Peter was incredibly kind to me, and his course on Joyce really changed my life,” Mueenuddin says. “I started by loving Dubliners and then A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which stroked my ego because I thought of myself as this budding artist. And then finally there was Ulysses, which I’ve read so many times that I don’t read it from the beginning anymore; I just open it at some random page and start reading it, like some people do with the Bible.” He laughs at the memory of his Dartmouth persona. “I was sort of misanthropic. I would wear this enormous overcoat and big boots, stand on the steps of the library smoking Gitanes and think of the students passing by, ‘These children! What do they know about the great things of life?’ ”

Bien, now a professor emeritus of English and comparative literature, formed a different picture of his former student in those days. “We had him over to the house many times, and Daniyal was, and is, a real gentleman,” says Bien, who with his wife hosted Mueenuddin when the author revisited Dartmouth for a reading last year. “He was bicultural, of course, with experience in both America and that unbelievable farm in the hinterlands of Pakistan, and very sophisticated and somewhat aristocratic, I would say. He was very smart and very clever, but I wasn’t much aware of his plans to be a writer, not then. The talent was there, obviously, but no.”

After graduation Mueenuddin returned to Pakistan, where he took over management of the farm from his ailing father (the details of which he would recall in “Sameer and the Samosas,” a 2012 essay in The New Yorker). It was there, about halfway between Lahore and Karachi, that he found the material he would later explore in In Other Rooms. Still, he lacked confidence in his skills as a writer. He also resisted writing fiction, in part, as he realized years later, because that was his mother’s medium. “Fiction was Mom’s game, and I didn’t want to compete with her,” he says. “Beyond that, if I had my way, I’d much rather be a poet. They’re the ones who make the language dance. And it’s the poets who are the glamorous ones. It’s like the difference between a bomber pilot and a fighter pilot. The poets are the daring ones, with their silk scarf and goggles. We fiction writers are just lumbering along and occasionally pulling together a book.”

Discouraged with his writing, Mueenuddin decided to go to law school. He got a law degree at Yale, then became a litigator and corporate attorney at a large firm in New York City, where he worked for a few years before becoming disillusioned, even depressed. “I realized that we truly were the bad guys, representing the forces of evil, and did I really want to spend the rest of my time making rich people richer? I thought, ‘When you’re 80 years old will you feel good about that?’ And then I thought, ‘I’ll hate it.’ And finally I thought, ‘I’d rather be a bad writer than a good lawyer.’ ”

It was around that time that Mueenuddin had a frightening but ultimately illuminating dream. He dreamed he was a fighter pilot in a plane that was shot down. Ejecting in his parachute, he watched the plane crash, even as he himself was safe, and felt an enormous relief. “I thought, ‘I’m free,’ ” he recalls. “I told myself, ‘Think of yourself as post-dead now.’ And I decided that I was going to do exactly what I wanted—which was to write—and if I was a failure at it, I didn’t care. Daniyal Mueenuddin was this piece of dust that had walked around the earth for a while, and it didn’t matter if he succeeded. I had always worried, ‘Will I be good enough?’ And the eureka moment was, ‘It doesn’t matter if you’re good enough. Just do it.’ ”

Over a tasty lunch of bratwursts and lemonade on the University of Wisconsin campus, looking out over the shimmering expanse of Lake Mendota, Mueenuddin seems, for the moment, more Wisconsinite than Pakistani. He’s looking forward to the publication of I. Want. You. To., which as of press time had not yet been offered to publishers but, if all goes as planned, will see print in late 2014 or early the following year.

The book is partly homage to his mother, to whom he was very close. When she died in late 2009, Mueenuddin was about one-third of the way through writing a novel set in Pakistan, but her death changed everything. “It was a very traumatic time,” he says. “When Mom died I knew I had to write about something that had to do with America and, in some way, to do with her. I started writing it in 2010 and at the early stages it was very much her story. At some point I realized it wasn’t her story at all, but I was very interested in writing something that would bring me closer to Mom and help me understand who she was.”

Like his mother in her youth, his novel’s main character Kristal is beautiful and intelligent; also like his mother, she moves to New York. “It’s about money,” Mueenuddin says carefully, “the ways in which money shapes our lives. It’s about a woman who trades her looks and intelligence for a type of life that initially seems very attractive and then, when she achieves it, turns out to be not so attractive. At each stage things sort of fall in on her, and she keeps on going to the next stage. At the end there’s a betrayal.”

Although his father’s grave is in Lahore, his mother is buried on the farm in Elroy, and Mueenuddin already has a plot near hers. During their summer in Madison he and his wife retreated to Elroy every weekend, enjoying the house, the neighbors (both Amish and “English,” as the Amish call all non-Amish people), the beer and the brats, the roaming buffalo. At every gathering the author—half-local, half-foreigner, at home and not—observes and listens carefully, always on the lookout for the telling detail that will one day find a home in a story.

Kevin Nance, a regular contributor to The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and Poets & Writers Magazine, lives in Chicago.

Sneak Preview

I. Want. You. To.

Author Daniyal Mueenuddin shares an excerpt from his work in progress.

The grass around the house had already, now in early June, become too tall for Kristal’s brothers to hack it down with the push-mower, though they brandished it on its hind wheels like a whirling shield, and now they would have to do it with corn knives. Her aloof bearing, the sharp animal contrast of her brown hair with her pale skin, made her more a thing of the fields and woods around the house, than of the bleak brick crumbling house itself. The door when she pushed it open made a whoofing sound. Her dad and the boys, when the winter came, when the first snow had already blown, sealed the house down tight, doing this one thing well, covering the north wall outside with a blue tarp against the coldest winds, the windows sealed with plastic, foam sheets in the frames inside, making the house dark as a cave, intensely warm from the woodstove all winter, and still now too warm, no draft coming in. Her two brothers were sitting at the kitchen table, while something bubbled on the stove.

“What’s that?” she asked.

“Pea soup. Dad got a crate at the dollar store. Just the cans are dented.”

The two boys, twins, looked feral, their white-blond hair badly cut by their father, roughly, so that their ears bled with scissor nicks when he did it. Pale skin, living in this cave. Eleven years old, and already in trouble at school. Ashtrays filled with twisted butts and beer cans, empty cigarette packs, covered every flat surface in the room, except an area cleared for cooking, the interior furred with debris, as if subterranean mushrooms were being grown on every horizontal surface. The best light in the room came from the TV in the corner, never turned off, only three channels from the expensive antenna Amel had rigged on a hill with money they didn’t have. His big easy chair that leaned back, the Barcalounger, the Beast they called it, faced the TV, but on the Saturday he would be at Augie’s Tavern. A red steel pole, a screw-jack, held up a beam in the middle of the room.

Going up the stairs, she inhaled the dirty heavy air, which to her seemed sweet, the air of going to sleep, of the house that she couldn’t escape, not before, and that had formed her refuge from the angularities and brightness of school and the outside world, where she had managed with such rigor to pass as someone clean and silent, moving through the corridors between classes without speaking to anyone, and protected from the bullying of her classmates by her icebound almost savage air, thin as she was, without breasts, wearing white blouses, washed too often, repelling the heavy-footed advances of the boys who in her senior year belatedly recognized her apartness as beauty. At thirteen she had painted her room bright colors, pink and pale blue, and every summer would plan to repaint it white; but didn’t finally, knowing that she would leave when she could, and never again sleep in this room. She kept it immaculate, another reproach to her family, another element in her fantasy of her own separateness. Sitting cross-legged on her bed, she looked out the window. This had been her entire world, this view up the valley, up into Pedretti’s long rich pasture. A day like this could reconcile her to the room, if not to the house. From today she would be living in town, a place she barely knew, because her family skirted it, rejected its order, embracing an outlaw secrecy, outlaw pride, her father and the boys poaching deer, picking through other people’s posted woods, fishing their ponds secretly, trapping coon and otter, muskrats, living on welfare checks and handouts from the churches, a turkey at Thanksgiving, cheap toys for the children at Christmas. Everything she wanted from this room fit into the two cardboard boxes that she slowly packed, fetching them up from the cool earth-smelling basement, a few jeans, the right ones that she bought with her own money, Levis from the big stores on the highway to Madison, the Royall jacket, the plush toys that a boy won for her at the fair, the fur still clean two years later.

She went into her mother’s room, one of the boxes held protectively in front of her.

“I’m leaving,” she said. Her mother lay on the bed, enormous, in a ragged pink bathrobe, reading a book cross-eyed. She lived through boxes of romances that she bought from the Piggly Wiggly, where they more or less stocked them for her, her and a few others. Along one wall were the discarded books, piled neatly as if she were filing them after use, and along the other, empty jugs of fortified wine, which she said didn’t get her drunk. When the room filled up Kristal would help her, carry the bottles to the back and throw them in the ravine, and box the books to be sold at the second-hand store.

“Where you going?”

“I’m leaving. I got a job.” Kristal could see she was pretty bad.

She rolled over and sat up, her bare feet enormously veined and swollen. “Wait till your dad finds out. He’ll belt you good.”

“Not any more he won’t.”

The mother took a book from the floor, leaning down heavily, almost toppling to the side. “You want this one? It’s pretty good, I just got done with it.” Kristal and her mother had shared these books for years, the romances.

“Thanks Ma.”

“Tell me if you like it.”

“I will.”

A cunning conspiratorial look came into her mother’s eyes. “You’re cuttin’ out, aren’t you. Wait till your dad finds out.”