The Dartmouth Caucus

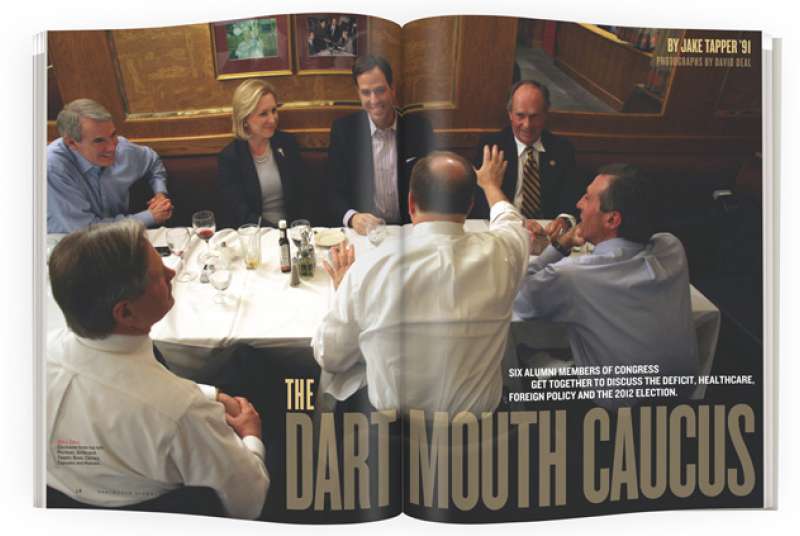

We meet at The Monocle, a posh restaurant on the Senate side of the Capitol. The six members of the Dartmouth caucus pile into our back table, one after the other, on the evening of March 29: First comes the feisty liberal former mayor of Somerville, Rep. Michael Capuano ’73 (D-Mass.), then comes a former governor, freshman Sen. John Hoeven ’79 (R-N.D.).

Rep. Charlie Bass ’74 (R-N.H.) enters in his absent-minded-professor way. Swept out of office in the Democratic wave of 2006, he returned to Washington, D.C., in the GOP wave of 2010. Next is freshman Rep. John Carney ’78 (D-Del.), the only Democrat to win an open House seat last year. The class’ most high-profile member, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand ’88 (D-N.Y.), brings an aide. Uncharacteristically last to the table is Sen. Rob Portman ’78 (R-Ohio), who served previously in the House, then as George W. Bush’s director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) after a stint as U.S. trade representative.

Three congressmen, three senators. Three Republicans, three Democrats. Our alumni run the political gamut. Three of them were part of DAM’s alumni caucus roundtable 11 years ago: Portman, back when he was a congressman, Capuano and Bass. Three are newer to the nation’s capitol. This time the conversation started with memories of Dartmouth and eventually turned to policy, partisanship and the ways of Washington, where the following edited transcript begins.

DAM: Congressman Capuano, is your job the best you’ve ever had?

CAPUANO: No. Mayor was.

DAM: Why?

CAPUANO: You’re the executive.

HOEVEN: I’d agree with that. I was a governor for 10 years and it was a great thing—you set out to do something, you can go after it.

DAM: Was that a consideration when you ran for Senate? Going from an executive job, where you run the state, to being one of 100?

HOEVEN: You know, it has been a transition. I’m still trying to get through separating activity from really focusing on things that I think will make a difference. I’m still kind of working through that part of it. But, you know, as governor I got to work with U.S. Trade Rep. Rob Portman. And OMB director Rob Portman.

DAM: What does North Dakota trade?

PORTMAN: Everything.

HOEVEN: We lead the nation in 14 different major commodities. As a matter of fact, we’ve had the fastest growth in trade for about two or three out of the last five years. North Dakota also has 3.5-percent unemployment, the lowest unemployment rate in the country.

PORTMAN: I was in the House, and then these two administration jobs where I was at the U.S. trade representative’s office, as Sen. Hoeven says, and I had about 250 to 300 people working there and then about 500 or so people at OMB. And I loved those jobs, because you’re managing people and focus a little more on results, rather than trying to pull together a consensus on the legislative side. On the other hand, the issues that we’re dealing with in Congress right now are I think the most pressing issues we face as a country. So for all of us it’s a time to serve, to try to make a difference.

DAM: How bad is partisanship these days? Is the tone in the country getting worse?

GILLIBRAND: I think the tone in the country has declined over the last decade. And one of the goals I have in serving is to really focus on bipartisan efforts, trying to create consensus, bring the different views together.

DAM: Why is it getting worse?

GILLIBRAND: Because the politics of division, the politics of hate, the politics of fear are effective. And I think too often the parties use those politics because of their effectiveness. My goal is to really put partisan politics aside and to try to bring people together on issues we can all agree on. For the last Congress I worked really hard on two issues that ultimately succeeded because they were bipartisan: repealing Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, and the 9/11 health bill for our first-responders who climbed up the towers, looked for survivors, then remains, and did the hard work of cleanup, who are now dying of these awful cancers caused by toxins released from the towers. So I think you can make a difference and it can lead to consensus on issues that don’t need to be ideological.

DAM: Congressman Capuano, you’re more of a pugilistic progressive. You’re not necessarily always talking consensus—you’re fighting for the principles you believe in. Do you think that the tone is worse?

CAPUANO: I think the divide is getting broader because the people who come here are significantly different philosophically. I don’t think the tone has changed. I don’t think the tone matters. What matters is what people believe in. And that has very significantly changed.

GILLIBRAND: The House is different from the Senate. My experience in the House was that the parties more often than not were voting lockstep. In the House the politics is really driven by caucuses, by collective action, by large groups voting the block. That’s how you use power and influence outcomes. I think we’re seeing that with the Tea Party movement today, how they’re trying to influence outcomes by voting in a block. In the Senate people have an opportunity to work on issues over years and create compromise and build consensus. It’s a different body, a different time horizon, so it allows for more consensus-building.

DAM: Congressman Carney, what was your job before you were elected to Congress?

CARNEY: In the year-and-a-half from the time that I lost the primary for governor in 2008 till the election in 2010, I worked for a green technology company. Prior to that I was in public service, after my football coaching days ended. I realized one day that I didn’t really want my future to depend on how 22 young men performed on a given Saturday afternoon. So I got into a business where your future depends on how a couple hundred-thousand people vote on a given Tuesday in November. I’m not sure that was a good tradeoff.

DAM: Or a couple thousand, as the case may be.

CARNEY: Or 1,700 [the margin of his defeat in Delaware’s 2008 gubernatorial primary].

DAM: What do you think about the tone in today’s politics?

CARNEY: My experience in Delaware is probably very different, because we’re so small, not very partisan. I’m used to working with Democrats and Republicans, just trying to get things done. We don’t have the extremes as much as you see in the Congress.

DAM: Congressman Bass, is it fair to say that you’re a moderate Republican? Or you were, at least, 11 years ago.

[Laughter]

BASS: Thank you for that introduction.

[Laughter]

DAM: Your party has changed a bit in the House with this influx of the Tea Party.

BASS: Well, I would suggest that the party is more conservative than it has been in the past. My father [Rep. Perkins Bass ’34, R-N.H.] used to complain to me all the time, saying, “You guys don’t know how to get along with each other. You fight all the time” and “When I was there everybody got along. My roommate was a Democrat” and all that stuff. I said, “Well, Dad, you were in Congress for eight years and Sam Rayburn [D-Tex.] was the speaker. During that eight-year period how many bills did you introduce that were passed?” And he looked at me and he said, “None.” Well that’s not my definition of bipartisanship.

I was somewhat unique in that I was elected as a freshman the year the Republicans took over in 1995, and I was elected again as a freshman the year the Republicans took over in 2011. My one observation about the differences is that Republicans in 1995 had no idea how to be a majority, and Democrats hadn’t a clue how to be a minority. The Republicans were terrified of presiding, frankly, and running the Congress, because they didn’t know how to do it. And the Democrats were just incensed that 40 years of rule had come to an end. It’s different now. I think that the Republicans are a more professional majority and the Democrats understand because they’ve been in the minority and in the majority. And I find the relationship better now than it was in 1995 and 1996. As far as political philosophy is concerned, there’s nothing I can say or do to pigeonhole myself as a moderate or a conservative. I happen to believe that the social agenda is not a big priority for the U.S. Congress, but fiscally I believe we’ve got to get spending and debt under control.

PORTMAN: I came in just before Charlie, in 1993, and I actually had a different experience than those who say that the House is so partisan. I guess I sort of disagree—I think you can still get things done, even in an environment that might be more partisan at the leadership level. Thinking about you and your dad, Charlie, I got 12 bills signed into law by Bill Clinton when I was in the House, bills that I wrote. I’m a pretty conservative guy, but I’ve always been able to get stuff done. Let’s see how it works in the Senate. So far, so good.

DAM: Were the bills all economic?

PORTMAN: We had two things with the Contract with America. One was unfunded mandate reform, which I guess is economic. The others were expanding 401(k)s and IRAs. [Maryland Democratic then-Congressman, now Sen. Ben] Cardin and I did three bills on retirement savings and then three bills on substance abuse and drug prevention. So it’s a mix. But the point is [to Carney] you did it. I look back at your career in Delaware, and you’ve always worked across the aisle. Even Capuano has voted for my Republican stuff. He won’t admit it.

CAPUANO: It was a mistake.

[Laughter]

DAM: We’ll edit out what Portman said. We don’t want that being used against you in a primary.

[Laughter]

PORTMAN: But you can still get stuff done in this town, I think. I agree the Senate is an easier place to get things done, because it’s a smaller body and we’re elected for a longer period of time.

GILLIBRAND: I think fiscal issues and economic issues are not ideological—it is a playing field where we can have common ground. I have no doubt that if we focus our efforts in this Congress on the economy and good pro-growth job ideas, some of those ideas are just plain-old good ideas. They’re not Democratic, they’re not Republican, they’re just good ideas.

CARNEY: But they are ideological to a degree, because we just spent two weeks in the House cutting out mortgage foreclosure mitigation programs.

GILLIBRAND: We’ll have different preferences.

HOEVEN: There are different philosophies, and different people have different ideas, but I think you still have to try to find a way to work with people. A good example, [West Virginia Democratic Sen. and former Gov.] Joe Manchin’s a very good friend of mine, and for six years we crossed over as governors, and we’re already cosponsoring legislation.

DAM: What do you think is the biggest threat facing this nation?

HOEVEN: I think No. 1, we’ve got to create a pro-business environment and get people back to work. We’ve got to remember that job creation and jobs—that’s the engine that drives this country. Second, we’ve got to get a grip on spending. We’ve got a great opportunity in energy and we should get out there.

DAM: Congressman Capuano, what’s the biggest threat facing our country?

CAPUANO: The deficit.

DAM: I’m surprised to hear you say that.

CAPUANO: There’s some commonality right there. It’s how you fix it where we’re not going to find very much common ground. I want to clarify something about partisanship. I have never once cast a vote because of a Democrat or against a Republican, but I have strong philosophical beliefs that generally fall on party lines. Parties mean something, and they have general philosophies. It’s not about personalities, because I like most of the members of the House. And I probably like as many Republicans as I do Democrats. But that’s not the point. The point is why did I come here? I came here to change the world, and not just “to get something done.” I don’t want to get something done if the something is bad. If the something is bad then my job is to stop that from getting done. Party affiliation is circumstantial. I have never voted along party lines for the simple purpose of voting for my party.

DAM: There’s so much talk about the 12 percent of the budget that is discretionary domestic spending, whether it’s NPR or Planned Parenthood or whatever. But everybody knows that the real issue with the debt and the deficit is Medicare and Medicaid and the Pentagon. That’s where the money is.

CAPUANO: All of those items are off the table. How are you going to get serious about taking care of this if you take those items off the table for serious discussion? Every one of them was not allowed to be touched in the House.

DAM: And it’s always this way, whether it’s the Democrats in charge or the Republicans in charge, and nobody wants to say, “If you make more than $150,000 a year you shouldn’t have….”

CAPUANO: Social Security?

DAM: Well, Social Security or Medicare.

CAPUANO: Until we put those things on the table for serious discussion, nothing will change and we will end up with worse partisanship. You know, here we are balancing the budget; what’s the first thing we do? Cut fuel assistance. What’s the next thing we do? Cut WIC [the federally funded health and nutrition program for women, infants and children]. That’s the way we’re going to balance the budget? Then the answer is yeah, now you’re into partisanship, a philosophical partisanship, because there’s no way in the world that I’m going to start with that.

I may end with that. But you throw those issues on the table as the only thing we can talk about? We can’t even discuss whether we should change the age for Social Security, whether we should change some of the criteria for Medicare? We can’t touch anything in the defense budget, but we can slash heating, fuel assistance and WIC? That’s not a basis for bipartisanship or cooperation, it’s a partisan statement that is the beginning of the conversation. Fine, that’s the conversation we’ll have, but I don’t want to be part of it.

DAM: Here’s where I wonder if the Tea Party movement will actually change matters. Mississippi GOP Gov. Haley Barbour said anybody who thinks there’s no money to cut out of the Pentagon has never been to the Pentagon.

CAPUANO: He’s right.

BASS: And it’s interesting, because the other guy who said that was Rep. Sam Johnson (R-Tex.), who was a POW in Vietnam for God knows how many years. And he said you can get $100 billion out of the defense budget.

HOEVEN: Well, the ramp-down in the war in Afghanistan alone will reduce about $40 billion based on the current plan. So there are reductions that are anticipated from that.

BASS: Yeah, when does that ramp-down happen?

HOEVEN: Over the course of next year, according to [Defense] Secretary Robert Gates.

CARNEY: The reality is we’re going to have to do it all. And the 10,000-pound gorilla is healthcare. And guess what, not many people have any good ideas about how to fix it. A Dartmouth Medical School study a few years ago showed that geographic areas that spent the most didn’t get any better results. The unfunded liability of Medicare is seven times the unfunded liability in Social Security. There are not many good ideas about how to bring down healthcare costs, and that’s really what we have to do.

DAM: Sen. Portman, this is your wheelhouse.

PORTMAN: John just said it: The biggest problem is healthcare. And it’s partly because healthcare impacts the economy by having costs that are double what other developed countries are paying. But it also is because healthcare drives the cost increases in Medicare and Medicaid. So this year healthcare costs are going to increase 9 percent, Medicare and Medicaid are going to increase just under 9 percent. That’s unsustainable. We’re talking about three, four times inflation. So I agree, those are areas that have to be addressed, but everything has to be addressed. Nothing is sacred now. Everything has to be considered

DAM: But who’s actually willing to say, “If you make a certain amount of income you can get back what you paid into Social Security, but that’s it? If you make this amount, you don’t get Medicare?”

CAPUANO: You’ve got to throw everything on the table, which is why it amazes me that when you talk about budget deficits we can’t talk about any tax issue. We can only talk about one-half of the ledger. There isn’t a business in the world that only looks at one-half of the ledger. I think it’s legitimate not to do certain things, but there’s no legitimate economic argument for what we just did in December [extending the lower tax rates for higher-income earners pushed by President Bush in 2001 and 2003]. None. Yet we did it. Why? Because it was politically expedient, it was easy, it fit everybody’s vote.

There’s no economic reason why we did what we did. None. And yet we did it. And everybody loves their talking points and uses them, and that’s all well and good, but you can’t find me five economists at Dartmouth or any other college who will tell you what we did was necessary for the economy. You can’t find them.

DAM: Congressman Bass, do you want to weigh in….Well, you don’t have to fight with Congressman Capuano….

BASS: [Smiling] No, no, I’m not going to fight with Mike.

GILLIBRAND: [Laughing] I think you’re egging them on.

DAM: You don’t have to physically fight with him.

BASS: The biggest issues facing this country are Medicaid, Medicare and Social Security. Social Security and Medicare are programs that are essentially owned by the American people: They’re financed by employers and employees, and for the most part they’re supposed to operate independently. The question is how we will reform, preserve and protect—whatever terminology you want to use—Medicare and Social Security when the American people want us to and they support it. And the only way you’re going to find out about that is to give them a chance to have a choice.

Now suppose you took the blue-ribbon commission on deficit reduction and presented it to the American people and asked them if they supported it. We’ve never had a national referendum in this country on anything, but if you took an independent commission, put together a plan for Social Security that might include tax increases, and you put it to the American people and said, “This is your retirement plan. If you support it, send it to us and we’ll pass it in Congress.” People get up in town meetings and they say, “When are you guys going to have the courage to do…” and it’s usually something that nobody supports—

CARNEY: “…to do what we don’t want you to do.”

[Laughter]

BASS: …and I think, “As soon as you guys have the courage to say you want it.”

DAM: Congressman Carney just said, “To do what we don’t want you to do,” because the American people think, according to polling, that all you have to do is eliminate waste, fraud and abuse, and foreign aid—which they think is 25 percent of the budget, as opposed to 1 percent of the budget—and then the budget will take care of itself. People complain to me about what network news puts on TV, what networks put on TV, and I say, “Then tell people to stop watching the crap. Tell people to start watching Frontline in numbers in the tens of millions, and that’s all you’ll get, excellent documentaries every night on television.” But until then you’re going to get….

CAPUANO: I want Dancing with the Politicians.

CARNEY: I heard some commentator the other day say that what it’s going to take for Social Security is for the leaders, the president, Speaker Boehner, somebody in leadership on the Republican side to do like Tip O’Neill and Ronald Reagan did in the mid-1980s: put their hands on the hot griddle at the same time. I mean there are only a few things you can do. Because of various factors people are getting more benefit than was expected in the agreement around 1986, presumably because of life expectancy and other factors. I mean think about life expectancy and what that’s going to do to healthcare costs. Healthcare is where the money is, and there are precious few ideas about how to bring those costs down. I had a great conversation on the train recently with my old high school football coach. He’s got two artificial hips now, and I asked, “How are those artificial hips?” He said, “Oh, they’re great. You know, I had them checked out.” Think about it, did you know anybody when we were in college who had an artificial knee or hip? No.

BASS: Forty years ago the therapy for a heart attack was bed rest and glycerin pills, that was it.

CAPUANO: I don’t know anybody who says, “No, I don’t want that extra MRI. Nope, I do not want that heart transplant.” Well I’ll say this: My father needs a cataract operation. He’s 98 and he said, “Forget it.” [Laughter] But that’s the exception. At the same time, my mother passed away last year. Last six months of her life I have no idea what it cost, a small fortune.

CARNEY: Rob probably knows the number. It’s a huge percentage of the healthcare dollar that’s spent on the last six months of life.

BASS: It’s hard to die.

DAM: It’s like 25 percent, isn’t it?

PORTMAN: If you add the last two years it’s about 50 percent, sometimes 70 percent. Last six months at a rate of 25 to 30 percent.

DAM: And there’s no guarantee that this is actually making these individuals live longer.

CARNEY: There is a guarantee that you’re going to die.

DAM: The dying is the only guarantee, but you’re not necessarily making their last two years more comfortable.

CAPUANO: But the minute you talk about it, the minute you even throw it on the table, what do you get in return? Death panel. “You’re trying to kill my mother.” So you know what that does? Everybody stops talking. Okay, we’re not going to talk about this anymore, which is a great recipe for disaster.

DAM: The demagoguery goes both ways.

CAPUANO: I totally agree.

GILLIBRAND: Last year alone we paid more than $400 billion of interest on the debt. But the quickest way to reduce the debt and the deficit is to create a growing economy, and that’s one part of the equation that we have not spent any time in this Congress talking about. That’s the part where I think we can have vast agreement, creating pro-growth policies to create a growing economy. But four things have to be on the table at the same time: a pro-growth economy, tax policy, discretionary spending and retirement spending. If you’re not willing to discuss all in a holistic approach you’re never going to be able to reach a consensus. If you’re not willing to take each of the four components and put them on the table together, you’re just talking about the edges, and you won’t solve the problems.

DAM: Here’s the challenge: You can get a bill to reduce the debt and you will like 50 percent of it. But you will hate the other 50 percent. It will be against what you stand for. For instance, it will raise taxes, Sen. Hoeven. Or it will cut benefits, Sen. Gillibrand.

GILLIBRAND: Right, for early childhood education or all the things that I support.

CARNEY: It’s the only way to get home.

DAM: And everybody knows that’s the only way it can be done.

CAPUANO: But I can’t support it if it’s 10-percent yes, 90-percent no. And that’s the problem. I mean when you piecemeal it out and you come at people like me, first off cutting fuel assistance, WIC and on and on and on. No discussion of anything else, we just passed a tax bill that is obscene. And the next thing is should we go after another tax bill? By the way, I probably have the wealthiest district of anybody here, so my constituents actually would’ve benefited more than anyone else’s.

DAM: [Pointing to Gillibrand] She actually represents Wall Street.

CAPUANO: She has Wall Street, but she has upstate New York as well. So on a per-capita basis I’m guessing my district is the wealthiest district.

DAM: Fair enough. Congressman Carney comes from the corporate state. The entire state is owned by credit card companies.

CAPUANO: Yeah, but they don’t make the money. They just allow them to make the money and ship it out.

DAM: They don’t even have a sales tax.

GILLIBRAND: You don’t have a sales tax?

CARNEY: We do not have a sales tax.

BASS: We don’t have a sales or income tax.

DAM: I want to switch gears for a second. As we are sitting here, Tomahawks are falling upon Libya, and this whole Libya debate has brought up the idea of what the role of the United States is in the world. What is our responsibility? What is the Carney doctrine?

CARNEY: We just had a long discussion about budget deficits. And part of the reason we’re in this fix is that we had two wars that weren’t paid for. How much have we spent, $1 trillion? $1.5 trillion?

DAM: Do you think the United States has an obligation to intervene to prevent a massacre?

CARNEY: I think there are times when the United States has an obligation to step up as the world power, but there have got to be limits to that. I’m not convinced that the president has drawn boundaries around this current engagement. I’m not convinced, frankly, that Libya meets that test of national interest.

BASS: I think it depends on where it is. You know, a massacre occurring in our sphere of influence is more significant. Libya is, or was at least in modern times, a colony of Italy. The oil goes to Europe. The Europeans have to take a bigger role in this. I’m weary of Afghanistan. I think that we as a country need to assess the path that we’re following in that we have to keep peace and stability everywhere. We may be better than anybody else in our military capability and our resources and so forth, but that isn’t going to last. Oil is at stake in Libya. Libya has a stronger air force. We didn’t lift a finger in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, and now here we are, putting everything on the line for the 1.5 million barrels of oil that go out of Libya, primarily to Europe. And the Germans may be involved, but they can’t even fight. You know, other people can’t fight at night, other ones can’t do this or that. We’re the only ones who do everything. And I just think that’s wrong.

DAM: What do the people of Fargo think about what our role should be?

HOEVEN: Qaddafi is a dictator. He’s a terrorist. He’s not only killing his own people to stay in power, but he’s killed Americans, as in the Lockerbie bombing. And I think with our allies and with the support of the Arab League, with the support of the North African countries, we should find a way to do everything we can to help the Libyan people remove him from power. I think that is in our interest, as Secretary Gates said, and doing it with our allies is something we should do.

DAM: This is such an interesting issue because it really has nothing to do with partisanship. Sen. Hoeven, the Obama administration could bring you out tomorrow to make that argument, but Democrats are making different arguments.

HOEVEN: We’re a big oil-producing state and we can get by without Libya’s oil. But I think you should also look at this as an opportunity to remove somebody—to help the people of that country, who want self-determination, remove somebody who is a thug and a terrorist and is killing people.

DAM: But there are thugs and terrorists and killers all over the world.

HOEVEN: We are about freedom. We are about liberty. We are about a world where there is self-determination and human rights.

CARNEY: Wasn’t that the argument in Iraq? A thug.

BASS: Well, weapons of mass destruction. I was on the intel committee during that period.

CAPUANO: I’m a traditional Republican on this issue. I’m non-interventionist unless we have a vested interest in it. I don’t see that adventurism works. Qaddafi’s a jerk. The world’s better off without him. No question about that. I’ve got a whole list of people like that. Honestly, I’m not against military intervention. I called for military intervention in Sudan in the middle of the genocide. Not now, but in the middle of the genocide I called for it, and nobody wanted to hear it then. And at least 500,000 people were slaughtered by their own government in an oil-producing state. It’s not a matter of can we do it, it’s a matter of should we do it. And no, in Libya I don’t think that we should. Again, there are exceptions to every rule, and I may make an exception to this case if I knew more about it. But I agree with Charlie, if it was going to be done, it should’ve been done by the Europeans. They’re the ones with the vested interest.

PORTMAN: I’m more in the Capuano and Bass pool probably. I just think that America’s ability to send forces is limited, partly because of our fiscal condition. We have to acknowledge that.

DAM: Joint Chiefs Chairman Admiral Mullen has called the debt the single biggest threat to our national security.

PORTMAN: If you think about it, every Tomahawk missile that’s being launched [in Libya] costs about $1 million. We’ve launched I think 191 of them. It’s on the credit card.

GILLIBRAND: We would all want to protect innocent lives in a humanitarian crisis. It’s a core American value. But we do not have unlimited resources, and when Secretary Gates made his determination early on that this particular engagement was very difficult in light of our commitments in Afghanistan and Iraq, that’s a very sobering comment, and one we have to weigh very carefully. Obviously President Obama felt the circumstances of this were unique because the Arab League asked for our engagement, because of NATO’s approval, because of the UN request and the allies’ participation in France and the United Kingdom. Qaddafi is a horrible terrorist. I mean he’s responsible for Pan-Am Flight 103, which killed many students from Syracuse in my state. It was a terrorist act that we are now learning was not only directed by the government, but by Qaddafi particularly. He is heinous and committing awful acts of terrorism against his own people. But we have to weigh each and every engagement carefully because of all of the concerns that have been expressed around the table.

DAM: Let’s look ahead to 2012. It’s going to be an interesting race.

GILLIBRAND: Well, I think the most important issue in the race will still be the economy, and the candidates, if they’re smart, will focus their time and attention on ideas for economic growth. I think the issue people are struggling most with is that the unemployment number in this country is still too high. You have to recognize even though stated unemployment is close to 9 percent, real unemployment is closer to 15 or 20 percent in some parts of this country. And we have pockets of unemployment, young veterans, for example, one in five unemployed right now, a 20-percent unemployment rate. That’s untenable. So I think the presidential election will be largely about different views of how you create an economy and how you address the worries that families are facing. When a family can’t meet the basic needs of paying its bills, whether it’s medical bills for aging parents or education for children or food bills or heating bills, the family is in crisis, and that is what drove the last election cycle. I think it’s what drove participation in the Tea Party. People just don’t know where else to go to voice their anger and concern and worry about their future.

DAM: Sen. Portman, do you hear any Republican presidential candidates out there—you don’t have to name names, if you don’t want to, although we’d love to hear them—talking about this in a way that you think will appeal to voters?

PORTMAN: Yeah, I do. [Speaking to Gillibrand] I actually agree with you—although we may disagree on some of the ways to get the economy moving—but I think if there is a Republican focus on how to deal with the jobs and economy issue and deficit issue, the Republicans are likely to be more successful. I think that’s one place where we sort of get off track sometimes as Republicans, because of listening to folks who have a specific concern. We mentioned the birthers and social issues earlier, but ultimately for most Republicans the top issue by far is jobs and the economy. And we do have a different philosophy from President Obama. He talks about the government playing a very active role, including the government in effect making decisions about which technologies ought to be supported or shouldn’t. And Republicans would take the view that instead of investing and spending more of the government money and choosing which technology, we should free up the private sector to do it through money market forces. That’s a legitimate debate.

DAM: Sen. Hoeven, the reality is that getting the fiscal house in order requires sacrifices, but nobody wants to be the one to propose to voters, “Well, you can’t get this medical treatment” or “If you make more than this, you’re not going to get the same Medicare benefits that you would’ve gotten five years ago.” Do you think Republican primary voters want to hear actual solutions?

HOEVEN: I’d go to a couple things. One is—Kirsten starts in the right place—we’ve got to get the economy going. From a Republican standpoint, that really does come down to creating the legal tax and regulatory certainty, a pro-business climate if you will, that encourages private investment and job creation. The Republican view is that private investment will get the economy going, not our government spending. Combine that with the fiscal discipline that Rob’s talking about, okay. Of course it’s got to be bipartisan, and then it’s got to be discretionary spending, entitlements, and tax reform to truly get on top of this thing. And I think the candidates will get traction. I may come from a governor’s perspective, but candidates like Mitch Daniels from Indiana, and Haley Barbour from Mississippi, who has tremendous broad-based experience and is very intelligent, understand government very well. [Editor’s note: In April Barbour said he will not run for president; in May Daniels said the same.] Tim Pawlenty from Minnesota has some good ideas. Romney will be back. I think you’re going to see a whole group of Republicans who are going to bring forward ideas in all these areas that will stimulate this debate in a very exciting and interesting way that will make for a great campaign.

DAM: Congressman Capuano, how was Mitt Romney as a governor?

CAPUANO: He was terrible.

DAM: You hear President Obama talk about “RomneyCare” as the model for “ObamaCare.”

CAPUANO: That’s all well and good, but unfortunately I happen to know Romney had nothing to do with the healthcare bill except vetoing the provisions to pay for it. Then his veto was overridden. Now we’re happy to call it RomneyCare in the primary because that’ll beat him.

CARNEY: Sounds like you’re about to hit the campaign trail for him.

CAPUANO: I’m looking forward to it.

DAM: The way you beat Romney is by praising RomneyCare, not disparaging it?

CAPUANO: Yeah, well, that’s—I can’t. I don’t lie very well.

DAM: As an early Obama supporter are you as disappointed as the progressive wing is?

CAPUANO: The progressive wing is never going to be satisfied with anything, as the Tea Partyers will never be satisfied with any Republican. I mean that’s the nature of life. But they will all universally vote for them for reelection. The question is how enthusiastic they will be.

CARNEY: On the Republican side the winning candidate has to go through Ohio, and based on something I read in one of the Hill newspapers, that means going through Sen. Portman, who might make a nice vice presidential candidate.

GILLIBRAND: You ready?

PORTMAN: No.

GILLIBRAND: Come on. Are you ready?

PORTMAN: No. No. Not at all.

CARNEY: And by the way, just listening to him tonight and knowing what I do of him, I think he’s the kind of person who would make a good vice presidential candidate for the Republicans, because the election, in my opinion, will be decided, as so many are, by that vast middle of the political spectrum, not the far right, not the far left. The decision-makers will be those people in the middle, which I think any Republican candidate with Sen. Portman on the ticket could have a shot at.

DAM: You think Portman’s a king-maker. What about Bass?

CARNEY: Well, he is too.

HOEVEN: Bass could run for president.

DAM: Are they already treating you as a king-maker? Are you already getting calls?

BASS: Yes.

DAM: I like that, an honest answer.

BASS: The Republican, if I can be a little parochial, who always says, “I agree” doesn’t do particularly well, at least where I live. You have to be willing to be a little like Mike Capuano and me and Rob Portman and say things that sound credible, that give you a unique mission that’s not just the Republican platform. We have had candidates on the Republican side, one after another, who have all the experience in the world, are great people and everything else and all they do is say, “I agree.” To be president you have to have something that people don’t necessarily agree with—they can disagree with you, but they understand why and they respect it. Those are the people who really catch on with the American people—they don’t tell the voters everything they want to hear. Obama didn’t tell the Democrats everything that they wanted to hear, but he gave them a feeling of hope and expectation. So the Republican candidate who can communicate that kind of unique mission will be the one who wins this election next year.

***

DAM: Let’s talk about Dartmouth. Congressman Bass, you’re the congressman from Dartmouth’s district. What does Dartmouth mean to you?

BASS: When I left Dartmouth I didn’t really think that I was significantly different than when I arrived.

DAM: What was your major?

BASS: Government and French, but I dropped the French major because I realized the best I could do with French was be an interpreter in the UN or something.

HOEVEN: Was Professor Rassias there then?

BASS: Rassias was there.

HOEVEN: Wasn’t he something?

BASS: And Jim Wright was teaching “Cowboys and Indians.”

DAM: You were not in a fraternity?

BASS: No. I lived across the street from Casque & Gauntlet at 9 South Main. It was better than any fraternity on the campus. I pulled out a couple of yearbooks maybe two or three years ago and I looked at what I was when I came there and what I was when I left, and there was no comparison at all. I learned how to write, I learned how to communicate, and I learned a lot about dealing with other people, which has been with me ever since. Four years is a long time to be in Hanover. The scope and breadth of the learning experience was vast. I learned an enormous amount about the world and about academics, but I didn’t realize it until after I’d left.

DAM: Congressman Carney, you were an athlete?

CARNEY: I got into Dartmouth because I played football. I went in as a quarterback and a defensive back and ended up playing defensive back for four years. I played lacrosse as well. So I was going to college to play sports.

DAM: How was the team that year, the four years?

CARNEY: We were good. But we never won the championship, which was a great disappointment for me. We should’ve won it my last two years.

HOEVEN: In 1979 they won.

CARNEY: Two seasons after I graduated. I was actually coaching the fall of 1978.

HOEVEN: You played with all the guys who won in 1979.

CARNEY: Yep. [Current coach] Buddy Teevens ’79 was a roommate of mine.

BASS: Did you play with Reggie [Williams] ’76?

CARNEY: I was a sophomore when Reggie played. He was incredible. And we had a good team that year. We tied Brown 10-10 on a fluke play at the end of the game. I remember as a sophomore playing at Harvard, and in those days we’d get 45,000 fans in the stadium, which was a mind-blowing experience. I was the kick returner, and being in the closed end of the stadium for the opening kickoff was quite an experience. But later in that half the guy that I played behind, who is an attorney in Boston, John Reidy ’76, got hurt. So I had to go in the game. And we were getting our butts kicked in the first half. They scored like two touchdowns right in a row. And I go into the huddle and there’s a guy by the name of Skip Cummins ’76, a linebacker who was meaner than Reggie Williams, and Kevin Young ’77, who was crazy.

PORTMAN: Skip’s girlfriend lived in my dorm.

CARNEY: Anyway, they were screaming at me, you know, “Don’t you mess up.” Fortunately, I didn’t. When I was being recruited by Tubby Raymond, head coach at University of Delaware, he’s sitting in my living room. I was starry-eyed. And I remember what he said to me that day: “If you want to be big in Delaware you’ll go to the University of Delaware.” I told that story to one of the Dartmouth alumni who was helping recruit me. He said, “Well, you know, if you want to be big anywhere in the country, you’ll go to Dartmouth.” I decided to go to Dartmouth. By the way, Tubby was right, if I’d gone to Delaware I wouldn’t have lost that primary for governor. Raymond actually ran a TV spot for my opponent. [In 2008 Delaware state treasurer Jack Markell defeated then-Lt. Gov. Carney 51 to 49 percent in the Democratic primary for governor.] But Dartmouth opened up a whole world. I was 12 years Catholic school, you know, old Irish-Catholic upbringing. Dartmouth opened up worlds that I had never known about or experienced. I made great friends there and actually could go back to Delaware and get elected to Congress. Not to governor, but to Congress.

DAM: Congressman Capuano, what did Dartmouth mean to you?

CAPUANO: Dartmouth made me a progressive. I came from my own working-class, urban area: Nobody was supposed to go to college, everybody was supposed to work. No one ever thought about an Ivy League education. Dartmouth made me realize the possibilities of life, made me realize that there are ways to make the world a better place to live in and helped me learn how to do it. It also opened my eyes to the barriers that entails: Most of the kids who went there had no clue what a tough life was like. None whatsoever. They thought they did, because they only had one maid and, you know, four cars in the family. It helped open my eyes. It gave me the impression that, committed, you can change the world. My freshman year was the year we shut down all the universities in the country.

DAM: Over Vietnam?

CAPUANO: Yeah. And we did it. And that meant a lot to me. It also opened my eyes as to the differences, the inequalities of the world. My classmates were smart, they were capable, but they were no smarter or no more capable than most of the people I knew [growing up], yet they were there. And other kids I knew never had the opportunity to do it. Nobody ever told them they could. I was told that I couldn’t. I was laughed at when I applied to Dartmouth early acceptance.

GILLIBRAND: By whom?

CAPUANO: Everybody in my city at the time, because nobody ever got there. I’ve got 34 colleges and universities in my district. I talk to college kids all the time. And I tell them all one thing: They’re smart, God gave them a brain, they should use it and they should appreciate it. But that doesn’t make them any better than the guy who’s coming in to clean up their coffee cups when they’re done in the room. That guy may not have the brain that they have, because God didn’t give it to him, God didn’t give him the opportunity, just didn’t have the breaks, whatever it might be. But that doesn’t make them better. I don’t know that if I had gone to a college in Boston at the time that I would’ve been able to see beyond what was effectively a conservative upbringing, that “it’s just all about me—go to a college, make money, be successful, move forward, if you can’t make it on your own, too bad.” Dartmouth opened my eyes, so I think Dartmouth therefore, in that case, was probably a miserable failure. [Laughter] Because I graduated more progressive than I ever thought that I would be.

DAM: Sen. Hoeven, you came from North Dakota….

HOEVEN: Talk about geographic oddity. How many North Dakota kids went to Dartmouth? For me it was a chance to meet people from all over, not only all over the country, but other countries as well. The diversity was tremendous to me, people from different places with different ideas and different talents and strengths. The other thing was the tremendous caliber of instruction. We had outstanding professors and small class sizes, so you really had a chance to learn adult problem-solving skills. I think Dartmouth did a remarkable job of preparing young people to go into challenging situations and decide what they wanted to do and how they wanted to do it. And I think each person here tonight has talked about that a little bit in different ways. That may be Dartmouth’s greatest gift.

DAM: Sen. Portman?

PORTMAN: This is more interesting to talk about than politics and policy. [Laughter] I was, you know, born and raised in Ohio, so my exposure to Dartmouth and all these different people, particularly East Coast people, was a great eye-opening experience for me. I got to know my professors. A lot of college kids just don’t get that opportunity because of big classes and their teachers doing a lot of research. I was an anthropology major and I knew all the professors.

HOEVEN: I thought you were a history major?

PORTMAN: I was everything. I was government, history, ended up anthropology. So that was unusual. I took five years because I just really liked this idea….

HOEVEN: [Smiling] I didn’t know they had a five-year plan.

PORTMAN: Well, my dad didn’t either. [Laughter] I took full advantage of the Dartmouth Plan and I always had to work when I wasn’t there. I worked for my congressman when I was a sophomore. And I never would’ve ended up in Congress probably without having that exposure. I didn’t know anybody in politics.

HOEVEN: Who was your congressman?

PORTMAN: Bill Gradison. I succeeded him 16 years after I interned for him.

GILLIBRAND: Wow.

HOEVEN: That’s remarkable. That’s pretty quick.

GILLIBRAND: That’s amazing. How many years were you in Congress?

PORTMAN: Twelve years. So Dartmouth gave me that opportunity. Ledyard Canoe Club had this Spirit of Exploration program, so we used Ledyard’s name and Dartmouth’s name to get a grant from Chrysler Co. for a truck, the Kayak Co. for big kayaks. National Geographic sponsored our trip and we spent six months kayaking down the Rio Grande from source to sea. I mean, only at Dartmouth can you do that. [Laughter] And we got credit for part of it.

DAM: No wonder it took five years.

BASS: Now that’s creative.

PORTMAN: It broadened my perspectives, but it also gave me just a lot of different experiences. I did go into private practice, the law, for about 10 years. But I always knew from the Dartmouth experience that public service was going to be in my future somewhere.

DAM: Sen. Gillibrand, you’re the first female Dartmouth alum to be elected to Congress. Was there anything that you experienced at Dartmouth that made that happen?

GILLIBRAND: Well, I found that Dartmouth really fostered debate. It didn’t tell you what position to have on any given issue, but it really fostered that individual growth by each student to not only form opinions, but then be comfortable to advocate your views.

DAM: Were you a government major?

GILLIBRAND: I considered government. But Dartmouth had a requirement that you take one class of a non-Western subject. I thought, “I’ll take Chinese and learn how to write my name in Chinese.” And I loved it so much that I decided to be an Asian studies major.

HOEVEN: Do you speak Mandarin?

GILLIBRAND: I did very well at one point. I went to China, I went to Taiwan, I studied in Asia for about seven months. And then I went back to India as a senior fellow and did more on China and Tibet. But what I loved about Dartmouth is it encouraged students to explore the world. Even in our song it says, “’round the girdled earth they roam,” and it’s all about us getting into the world and having an impact on the world, and I think that’s unique about Dartmouth. When I was looking at schools, that’s the reason I chose Dartmouth, because it encouraged more study abroad. I traveled a lot as a high school student to many countries, which is highly unusual. I wanted to continue that experience, because I learned so much about other cultures, other people, other priorities by traveling. It made me not only want to be part of this world, but also to be engaged in the issues of the day. And I think that fundamentally helped me move toward public service over the years.

Jake Tapper is the White House correspondent for ABC News.

Roll Call

A primer on Dartmouth’s Congressional caucus.

Rep. Charles Bass

Republican from New Hampshire’s 2nd Congressional District

House Energy and Commerce Committee, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing and Trade, Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, Subcommittee on Environment and Economy

Personal: 59; married to Lisa; two children

Professional: Field worker for Rep. William Cohen (R-Maine), 1974; chief of staff for Rep. David Emery (R-Maine), 1975-79; N.H. House of Representatives, 1982-88; N.H. Senate, 1988-92; N.H. businessman, Columbia Architectural Products and High Standards Inc., 1980-93, and board of managers, New England Wood Pellet, 2007-09

Contact: (202) 225-5206; www.house.gov/bass

Rep. Michael Capuano

Democrat from Massachusett’s 8th Congressional District

Committee on Financial Services, United States House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

Personal: 59; married to Barbara; two children

Professional: Somerville, Massachusetts, alderman, 1977-79; chief legal counsel, Massachusetts Legislature Taxation Committee, 1978-84; attorney, 1984-90; alderman-at-large, 1985-89; mayor, Somerville, 1989-98

Contact: (202) 225-5111; www.house.gov/capuano

Sen. Rob Portman

Republican from Ohio

Ways & Means Committee, Standards of Official Conduct Committee

Personal: 55; married to Jane; three children

Professional: Lawyer-lobbyist, 1984-88; associate counsel at the White House, 1989; deputy assistant and White House legislative affairs director, 1990-91; alternate, U.S. representative to UN Human Rights Committee, 1992; U.S. trade representative, 2005-06; U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio’s 2nd District, 1993-2005; Director of the Office of Management and Budget, 2006-2007; United States Senate, 2011

Contact: 202-224-3353; www.portman.senate.gov/

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand

Democrat from New York

Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry, Committee on Armed Services, Committee on Environment and Public Works, Committee on Foreign Relations, Special Committee on Aging

Personal: 44; married to Jonathan; two children

Professional: Attorney, 1991-2005; worker for Hillary Clinton’s Senate campaign, 2000; U.S. House of Representatives, 2007-09

Contact: (212) 688-6262; gillibrand.senate.gov

Rep. John C. Carney Jr.

Democrat from Delaware’s At-large District

Committee on Financial Services

Personal: 54; married to Tracey; two children

Professional: Lieutenant governor of Delaware, 2001-09; president and CEO of Transformative Technologies, 2009-10

Contact: (202) 225-2291; johncarney.house.gov

Sen. John Hoeven

Republican from North Dakota

Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forest, Committee on Appropriations, Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Committee on Indian Affairs

Personal: 54; married to Mikey; two children

Professional: President and CEO of the Bank of North Dakota, 1993-2000; governor of North Dakota, 2000-10

Contact: (202) 224-2551; hoeven.senate.gov

FROM THE ARCHIVES

To read Jake Tapper’s interview with the Dartmouth Alumni Caucus from the March 2000 issue of DAM (featuring Bass, Portman, Capuano and Don Sherwood ’63, click here.