The Contenders

Hannah Kearney ’15

When the gold medalist in freestyle skiing decided to enroll at Dartmouth she had to learn a whole new skill: sitting still.

Hannah Kearney has skis on the roof of her car. This isn’t all that surprising, given that she’s a professional mogul skier—and, by the way, Olympic gold medalist—except for one thing: It’s late October in her hometown of Norwich, Vermont, and the temperature is still in the mid-60s. Her class of 2015 classmates have barely finished fall midterms and snow seems a remote possibility.

Why the skis? “Those are for water-ramping,” she explains.

Water-ramping is how Kearney spends her summers: launching herself off enormous, Astroturf-covered jumps into a pool, wearing skis, boots and a wetsuit, to practice the flips and spins she needs to master in order to compete. From May through September she lived at the Olympic training facility in Lake Placid, New York, where the water ramps are located. During that time, she reckons, she splashed into the chilly water more than 1,000 times—1,180, to be exact, which she always is. She logs all her jumps, and even counted the total steps (69,920) she climbed back to the top of the takeoff hill.

She’s just back from Zermatt, Switzerland, where she spent three weeks training on a high-altitude glacier. But the training doesn’t stop. Yesterday she ran up Mount Ascutney. Today she spent the morning in the Dartmouth gym, hit the Co-Op for supplies and went out for a one-hour bike ride, which for an athlete of her caliber qualifies as “recovery.” Her nightlife will consist of stretching while watching her beloved Red Sox in the playoffs.

Starting tomorrow a film crew will be following her for two straight days, producing a commercial for a new sponsor, Liberty Mutual Insurance. Next week she’ll head to New York City to attend the annual Ski Ball, a fundraiser bash for the U.S. Ski Team, and to appear on the Today show in clothes from another new sponsor, Ralph Lauren. In November she flies out to Colorado for more on-snow training, back home to Vermont for Thanksgiving and finally off to Finland for the first World Cup race of the season in early December. There’s not a lot of downtime when you’re the defending Olympic champion.

Four years ago at the Vancouver Games Kearney stunned everyone by defeating the Canadian favorite, Jennifer Heil, in the mogul-skiing event. Now, going into Sochi, she’s the one with the bulls-eye on her ski suit—the reigning World Cup champion, the dominant female mogul skier of her generation and one of the winningest U.S. skiers in history.

“I’m ready,” she says. “Give me a day to train and I could compete tomorrow.”

All this training—thousands of hours, 12 months a year, on the water ramps, in the gym, on the trails, on the slopes, with no time for a boyfriend or any other distractions—is to prepare for two 30-second runs down a steep slope at Rosa Khutor Extreme Park, the Olympic freestyle venue at Sochi. There she will navigate a field of bumps the size of a VW Beetle, punctuated by two aerial tricks off jumps as high as your garden shed. In Vancouver she executed her trademark back layout, followed by a flawless 360-degree spin. Judges take into account her acrobatics, speed and, most importantly, the quality of her turns, which she honed on icy New England slopes, starting at the Dartmouth Skiway.

“I don’t even remember learning to ski,” she says. Her parents do: They put her on skis when she was 2. A few years later her mom, Jill, the recreation director for Norwich, enrolled her in the Ford Sayre freestyle program at the Skiway. There Hannah learned to love rugged terrain. “When you’re a kid the bumps at the side of the trail are the fun part of skiing,” she says. “They just seemed inherently more interesting.”

At 9 she entered her first mogul-skiing competition, at Waterville Valley, New Hampshire, and “didn’t even place,” she says. By 15 she had won a junior world title. At 16 she made the U.S. Ski Team and began juggling an international competition schedule with homework for Hanover High School. At 19 she was standing in the start house for her first Olympics, in Torino in 2006. And she blew it.

She was supposed to be in contention for a medal: She had won the World Championships the year before and had bagged a World Cup win that season. But the pressure proved too much for her. She failed to advance out of the qualifying round. There were tears, followed by a resolution that it would never happen again. “I wasn’t ‘just happy to be there,’ ” she says now. “I let everybody down.”

“Anything she did she did with real intensity, and she always wanted to win—whether it was putt-putt golf or Monopoly or any sport,” says her mother. “She was born with an extraordinary amount of competitive spirit.”

After Torino Kearney trained harder—and then blew out a knee in 2007, causing her to miss the rest of that season. After ACL surgery at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center she came roaring back. Now she was winning World Cups regularly, battling with the older Heil up until their showdown in Vancouver. When she came home to Norwich with gold, the town threw a parade for her. The governor came. Dan & Whit’s General Store hung up a victory banner.

“I think we all floated around for three or four months, sort of on this cloud of heaven,” says her mom. “Then she was like, ‘Okay, what am I gonna do now?’”

Her answer was to keep skiing, of course. But she also entered Dartmouth, the first 24-year-old, gold-medal-winning freshman in the history of the College. Her younger brother, Denny, now a professional hockey player in France, had already graduated from Yale, so it was time to start catching up to him. Dartmouth was the only place she applied: It was the school down the road, so she could live at home in the house her father built and that she shares with Denny when he’s home from hockey season. “I said if I get in, it’s a sign I should go to school,” she says. Bingo: She was accepted to the class of 2015 and showed up on campus in March of 2011.

After several years of traveling the world she found that student life was at least as challenging as training to be a world-class athlete. Maybe more so. She was out of place, for one thing—a female freshman five years older than her classmates, living six miles from campus with no dorm parties or freshman-trip bonding experiences to share. Instead of spending hours in the gym or on the hill, she was spending her days and late evenings in the library or at her desk at home, practicing an unfamiliar skill: sitting still and studying. “It was terrible, to be honest,” she says. “I was really unhappy.”

It wasn’t the lack of a social life that bothered her. She was out of shape when it came to schoolwork. So she approached it the way she did her training: borderline-obsessively. “I’m the person who’s doing, like, 17 drafts of a paper,” she says. “In my mind I’m like, if I just let it go with the schoolwork, it might carry over to my next workout. If you’re satisfied, you’re never gonna get better.”

The hard work paid off with her first A on a paper in “Environmental Justice,” a freshman seminar, where she argued in favor (obviously) of building ski areas on National Forest land. But there always seemed to be more work than hours in the day. “I’m also the idiot who read every single word of everything that was assigned,” she laughs. “It turns out people don’t do that! But I was paying for every single cent of it myself, so I might as well.”

Because Kearney was an older, “independent” student, she was expected to pay full fare. The College determined that she could afford to spend up to 75 percent of her IRA, which she had carefully nurtured since the age of 16, on tuition. Nevertheless, she decided it was worth coming back for a second term in the spring of 2012. This time, things seemed to go better: She found that her favorite course was “Introduction to Biological Anthropology,” taught by professor Seth Dobson. “It was evolution, it was physiology, it was human society, and all that’s interesting to me,” she says. She still hasn’t made up her mind, major-wise, “but I can probably rule out the English-literature-y sorts of things.”

After Sochi, Kearney says she’ll ski for one more year, at which point she’ll be 28—getting oldish for a mogul skier—and then retire. She hopes to then become an oldish college sophomore with two gold medals. She’s already spent hours paging through the Dartmouth course catalogue, which sits on a shelf above her desk. “I’m like, wow, how do you choose?” she says. “It’s all interesting to me. There are a lot of dog-eared pages in that thing.”

—Bill Gifford ’88 (Gifford has written for Outside, Wired and Men’s Health. He is working on a book about the future of medicine.)

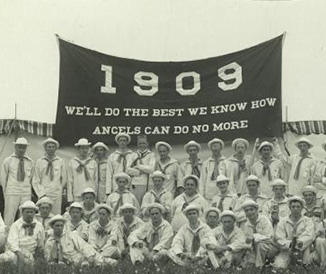

Andrew Weibrecht ’09

He’s called “Warhorse,” but the downhiller and 2010 bronze medalist is really just a speed freak.

When an overnight snowstorm canceled the men’s downhill training runs at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics, Andrew “Warhorse” Weibrecht and some of his American teammates went up higher onto Whistler Mountain to get in a few hours of powder skiing, just for the fun of it—something none of the single-focus European racers would have dreamed of doing. The next day Weibrecht finished 21st in the downhill. New Yorker writer Nick Paumgarten asked him if he planned to do any more free-skiing that week. “Naw,” Weibrecht told him. “My legs are cashed. I overdid it yesterday.”

That an Olympic athlete would go out and exhaust himself having fun just before the biggest race of his career wouldn’t surprise the skiers who came to know Weibrecht at Dartmouth. Nor would it surprise them that, four days later, on a flawless sunlit day, Weibrecht absolutely hurled himself down the hard-ice course in the Super-G competition, the hybrid event that grafts the speed of downhill onto the technical turning skills of slalom. Coming through the 180-degree turn through the heart-stopping, 58-degree slope called “the Fallaway,” Weibrecht caught an edge and nearly caught a gate. He skirted disaster at better than 80 m.p.h., almost losing control twice in the first 60 seconds. The run reminded observers of the stunning edge-of-mayhem World Cup run he made in a snowstorm at Beaver Creek in 2007, when he surged from 53rd to 10th and became a YouTube sensation.

The Whistler race was shaping up as pure Warhorse—a 5-foot, 6-inch, 190-pound cannonball shot of all-or-nothing speed. He held his line—always the fastest, most dangerous line—through the twisting curves into “Boyd’s Chin,” finished off turns 32 and 33 through the final technical section of “Murr’s Jump” and tucked it across the finish line at 1:30.65. He braked hard to stop and pumped his fist skyward, grinning wide. He had been the third, and fastest, racer down the course.

Next he waited and watched while 17 other racers flamed out or skied off course and 42 others flew across the finish line. In the unforgiving world of alpine ski racing, only two of those racers skied the course faster: The Norwegian champion Aksel Lund Svindal, at 1:30.34, and the greatest American alpine skier of all time, Bode Miller, at 1:30.62—just three one-hundredths of a second faster than the bronze-winning Weibrecht. The unexpected result put the unheralded Dartmouth student in fast company with Miller and women’s downhiller Lindsey Vonn on that week’s cover of Sports Illustrated.

It was Vonn’s former husband, downhiller Thomas Vonn—along with teammate Dane Spencer—who gave Weibrecht the name “Warhorse” when he was a rookie with the U.S. Ski Team. The nickname captured the way the new skier attacked the mountain. It stuck.

Almost four years after winning the bronze in Vancouver, following World Cup seasons interrupted by two shoulder surgeries and two ankle surgeries, Warhorse has earned the other definitions of the name: He’s still a charger, but he’s also become a veteran who has endured many struggles and battles.

He’s worked hard to get his strength and fitness back into top form. He’s finally feeling good again. He’s psyched about his new skis made by Head. It’s the first season in 25 years that he’s has raced on anything other than Rossignol. “By Sochi I should have the skis dialed in,” he says from his home in Lake Placid, New York, on a short break between the team’s speed camp in Portillo, Chile, and the final training camp about to start up in Colorado.

Like many top young racers, Weibrecht applied to Dartmouth just as he was starting out on the U.S. ski circuit. As his career progressed he made the decision to stay with the U.S. program and take advantage of Dartmouth’s unique quarter system to pick away at a degree one term at a time. There was some irony in his decision. During a fall term when he was still new to the U.S. Ski Team, long before Vancouver, Weibrecht was questioning whether he still had the fire to continue racing. Doing dry-land training with the Dartmouth skiers (“and just being in that atmosphere,” he says), he felt his passion reignite. Without Dartmouth there would have been no bronze medal.

“About half of the World Cup skiers connected to Dartmouth are like Andrew,” says Chip Knight, Dartmouth’s director of skiing, “especially in the men’s downhill. Many of the best skiers in the country apply here and then defer to see how their careers unfold. After a year or two a lot of them end up falling back on Dartmouth and skiing for us.” The other half typically enter Dartmouth as strong Winter Carnival-level skiers, get faster each year and make the World Cup team after graduating.

Graduating for Weibrecht will have to wait. At 27, he has three terms left to finish his degree but is running out of earth sciences classes to take during the one time of year—spring term—when he can devote himself to his studies. He admits to feeling increasingly old and “a little awkward” when he’s back on campus (though a more focused student). In September 2010 he married Denja Rand, and he is beginning to think he’ll likely finish off the remaining terms consecutively when his racing career is over.

That could be a while. The veteran is still young enough to have a lot of races left in him, perhaps even a third Olympics in 2018—but nothing, he says, left to prove. “The bronze medal gave my career legitimacy. Winning races depends on so much: speed, conditions, luck. There have been so many great racers who never had that result, and it’s something no one can take away from me.” The defending medalist isn’t concerned that he won’t be among the favorites in Sochi. “I’m only worried,” he says, getting to the pure heart of it, “about going fast.”

—Jim Collins ’84 (Collins divides his time between Seattle and Orange, New Hampshire.)

Gillian Apps ’06

The Team Canada veteran, born into a legendary hockey family, can’t imagine going through life without goals.

Midway through an exhibition game on a Thursday night in September, at the nearly empty WinSport Olympic training complex in Calgary, Alberta, Gillian Apps followed a rush up the ice from her familiar spot out on the left wing and slipped into an open space on the near side of the net. Using her long reach she gathered a loose puck and swept across the crease. The goalie, a 17-year-old on one of Calgary’s elite AAA men’s development teams, was caught out of position and frantically shifted to catch up with her. Apps held her course a fraction of a second longer, forcing the goalie to commit. She dipped her front shoulder to cock the lever on a wicked backhand shot—then slid the puck back across the crease to her streaking veteran teammate Hayley Wickenheiser, who buried it in the half-empty net.

The goal, in itself, was unremarkable. The Canadian women’s team long ago established a level of play that is dominant on the world stage, winning 10 of the past 14 world championships and gold medals at the past three Olympics. Today the women had already finished off several crisp sequences that would blur together with countless other well-executed plays on the way to a 7-2 thrashing of the U-18 Calgary Northstars. In the official Team Canada write-up of the game the following day, the Wickenheiser goal at 10:09 of the second period would warrant barely a mention.

For Apps, fighting for a spot on the Olympic roster, those few seconds stood out as symbolic. Once a rising teen star in Canada’s centralized Olympic training camp, Apps was now almost 30 years old—and a two-time gold medal winner. At the 2006 Games in Turin, Italy, she had been the third-highest scorer among all players. She is still a big power forward—at 6 feet tall and 175 pounds, the biggest player on the squad—and still plays the game with what one Canadian sports writer called “controlled recklessness.” But as a veteran her role has evolved. She is now looked to for intelligent, disciplined hockey at both ends of the rink, to forecheck, use her size to control the ice, dig loose pucks out of corners, fight for position in front of the opponent’s net, kill penalties and create opportunities for her teammates. She is one of 13 returning players from the Vancouver gold-medal team, all of them being pushed by an up-and-coming generation that’s faster, better trained and more skilled. With 27 roster spots getting trimmed to 21 by the end of December, none of the veterans’ positions were safe. On that Thursday night in Calgary, Apps’ 21-year-old linemate, Mélodie Daoust, scored two of the team’s seven goals. Apps’ contribution couldn’t be measured by statistics.

After the game she spun her legs for 15 minutes on a stationary bike, drank an energy drink and showered. Two months into the training camp she was feeling the grind of the six-day-a-week conditioning, the push of the 50-game exhibition schedule. Her body felt tired, but strong. “As you get older you need to train harder,” says Apps. “It’s really hard to tell where you stand. There are always younger players trying to take your spot. I’d say I’m not as secure right now as I was when I was 24 years old, but it all depends. Roles change. You just adapt to those changes.”

The fitness and strength of the younger players has forced Apps to become not just a better hockey player but a better athlete. She had added cycling and other cross-training to her year-round regimen. (In a 2010 Nike television ad Apps appears straining through a wind sprint, pulling the resistance of a speed chute behind her. Looking straight into the camera, catching her breath, she says, “Destiny doesn’t push this hard.”) The night of the exhibition game in Calgary she fell into bed after midnight in a modest furnished house five minutes from the training complex and rose at 7:30 the next morning, ready do it all over again.

The camp had reached the point where the coaches were experimenting with different lineups on the ice, trying to get at the intangible sense of a team’s chemistry. Dan Church, the new head coach, was relying on Apps as part of an informal “leadership group” of older players to serve as a bridge between the team and the coaching staff. He appreciated the way that Apps had embraced her changing role, the unusual combination of discipline and joy she brought to the game and her willingness to mentor younger players. For Church, there was more there, too, that was harder to put into words. He was once asked if something distinctive marked the hockey players who came out of the Ivy League. “Yes,” he said. “But not in the way they play. It’s something you see off the ice.”

Apps brings a lineage to the team that goes deeper than Dartmouth. Her father, Syl Apps Jr., was an all-star player in the National Hockey League. Her grandfather, Syl Apps Sr., was a three-time Stanley Cup winner with the Toronto Maple Leafs and a pole vaulter at the 1936 summer Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. She has a cousin who rowed in two Olympics. Her older sister played for a decade on the Canadian national soccer team before retiring, and her older brother skated for Princeton and spent four years in minor league hockey before pursuing a master’s degree.

Apps’ champion bloodlines compensated for her late start in the sport, which she picked up casually at the age of 12. “When I was working hard to make the national team I didn’t consciously think of my hockey as being part of a legacy,” she says. “Now that I’ve competed in the Olympics I feel honored to have contributed to the family tradition.”

Now she’s reached the age where it’s natural to start thinking about what might come after hockey. “I’m intrigued by the idea of getting an M.B.A. and seeing where that might lead,” she says when pushed about her future plans. “But right now I’m not thinking about anything except making this team and getting to Sochi.”

The grueling Olympic training camp came at a personal cost. Of the 27 women in Calgary, all but six had relocated from outside of Alberta. They’d put school or careers on hold and left behind homes, friends, husbands (only a couple of her teammates had married because the lifestyle discourages long-term relationships). They did it for low pay and Spartan living conditions, for the love of the game and for a kind of fame that spreads fleetingly into households across North America once every four years, then settles back into hockey camps and academies and cold ice rinks where young girls dream of Olympic gold.

With the retirement of teammate Cherie Piper ’06, Apps—if she makes it to Sochi—will carry the torch as Dartmouth’s lone representative in ice hockey, keeping alive a tradition that began with the introduction of the women’s event in the 1998 Nagano Games. There’s another Dartmouth player coming up behind her in the pipeline: Laura Stacey ’16, a highly touted member of Team Canada’s U-22 team. “I’ve been texting her a lot,” says Apps, who is savoring the competition and whose age in 2018 (35) wouldn’t automatically rule out a fourth Olympic attempt. “I’m keeping tabs on her.”

—Jim Collins ’84

ADDITIONAL SOCHI HOPEFULS

We caught up with College athletes—alums and undergraduates—as they readied for trials that would determine whether or not they will travel toa Russia for the Olympic Games to be held February 7-23. Interviews by Gavin Huang ’14 and Minae Seog ’14

Martin Anguita ’16

Alpine skiing (Chile)

Santiago, Chile

Engineering major 2011 and 2010 Chile National Champion; winner, two 2013 FIS slalom races

“My goal has always been to be NCAA champ. If I go to the Olympics, cool. I’m not as focused on them as other people would be because I’m taking classes winter term. I’m actually thinking about whether I want to go to the opening ceremony or not, because I’d miss a lot of races here and miss classes. It’s not that I don’t care about it, but I have so many other things going on.”

Dakota Blackhorse-von Jess ’09

Cross-country skiing

Bend, Oregon

Computer science major modified with environmental studies

Winner, 2013, 2nd, 2012 and 6th, 2011 U.S. National Championships

“My coach and I are really excited about qualifying, and things are lining up nicely. I’m think I’m fitter than I’ve ever been, which is sort of scary because if I am, I’m moving from a top-level national skier to a high-level international skier. Ultimately, the start line of a race is the start line of a race. All you can control is doing your very best to ski as fast as you can.”

Rosie Brennan ’11

Cross-country skiing

Park City, Utah

Geography major

Overall champion, 2013 USSA SuperTour; winner, 2013 U.S. National Championship 10K

“I set up the season very well last year by winning overall champion in the 2013 SuperTour circuit and earning start rights to the World Cup races this season. Of course I’m still nervous because I have to follow through and use this opportunity well, but it’s very exciting to have a crazy goal that only comes around every four years.”

Sophie Caldwell ’12

Cross-country skiing

Peru, Vermont

Psychology major

2013 U.S. Nordic Ski Team; 2nd, 2013 Slavic Cup and 2013 U.S. National Championship; 20th, 2013 World Ski Championships

“I had a great summer training and follow-up training and testing has been going well. Obviously, Olympics are my biggest goal, but sometimes that’s sort of overwhelming to think about. Instead I try to focus on the next camp, the next test ahead of me. Everything feels good so far. I hope my results will reflect that.”

David Chodounsky ’08

Alpine skiing

Crested Butte, Colorado

Earth science and engineering major

U.S. Ski Team since 2009; three top-20 2013 World Cup finishes

“I feel like I’m skiing a lot better and much better conditioned than in 2010, when I almost made the 2010 Olympic team. I started racing when I was 7. You have to put all your energy into it. We were off training in New Zealand in August and then Chile in September and all the time in between basically working out. I’d like to get to Sochi—and maybe win a medal while I’m at it. Most people in the United States aren’t sure that skiing really exists as a sport until the Olympics, so that’s the time to shine.”

Kieffer Christianson ’14

Alpine skiing

Anchorage, Alaska

Psychology major (expects to graduate in 2019)

U.S. Ski Team since 2011; Junior World Championships team, 2010-13; winner, 2013 Nor-Am giant slalom, Vail, Colorado, and 2013 Junior National giant slalom; 2013 Golden Ski Award

“When I come to school spring term it’s a total rewiring of my brain. When I go back to skiing I’m totally fired up. Initially I didn’t have that much interest in going to college, but my parents wanted me to go to Dartmouth. When I finally got there I was like, ‘Wow, this is awesome.’ Freshman orientation was the best week of my life. Now the tables are turned because, despite pressure to ski year round, I’ve made it a priority to enroll at Dartmouth at least one term a year.”

Hannah Dreissigacker ’09, Th’10

Biathlon

Morrisville, Vermont

Engineering major modified with studio art

2013 U.S. Biathlon and World Championship teams

“When you race in the United States, skiing—biathlon especially—is a tiny sport, but in Europe it’s huge. At the world championships last year there were 20,000 fans. The Olympics has a different feel. Our race will definitely have fewer than 20,000 spectators, but being part of something where all sports are in the same place will be cool. It gives you an understanding of everyone else and all the different sports. That’s what’s special about the Olympics.”

Susan Dunklee ’08

Biathlon

Barton, Vermont

Biology major with ecology focus

2013 U.S. Biathlon and World Championship teams; 5th, 2012 Biathlon World Championship

“I divide my summer between Craftsbury, Vermont, where I work at the Outdoor Center, and Lake Placid, New York, where the national biathlon team is based, and I always look forward to seeing my friends. Both communities feel like family. The big difference between the Olympics and world championships is more external pressure to do well.”

Erika Flowers ’12

Cross-country skiing

Bozeman, Montana

Geography major; premed track

8th, 2013 U.S. National Championship; 4th, 2012 U.S. National Championship and USSA SuperTour finals

“The Dartmouth ski program really fosters the ability to grow over the long term, rather than just focusing on the NCAAs. By being encouraged to attend international racing trips and U.S. national competitions, we are constantly exposed to a whole new level of racing. Cross-country skiing is definitely an individual sport, but the Dartmouth ski team provides a team atmosphere. We have everyone from the development team to people racing in the World Cups all working together to make each other better.”

Nolan Kasper ’14

Alpine skiing

Warren, Vermont

Undeclared major (expects to graduate in 2020)

U.S. Ski Team since 2008; 2010 U.S. Olympic team (24th, slalom, in Vancouver); 10 top-10 World Cup finishes, 2011-12

“U.S. skiing is very team-oriented, but when you race it’s you and no one else. Your best training partners are your biggest enemies. Spring term is a time to get my head going in a different direction and keep myself hungry for getting back into skiing in summer. After a pretty significant knee injury last year, I’m excited to get back to racing.”

Keith Moffat ’13

Alpine skiing

Berkeley, California

Engineering major (expects to graduate in 2016)

U.S. Ski Team since 2010; winner, 2012 South American Cup; 7th, 2012 U.S. National Championship; 4th, 2011 Junior World Championships

“Ski careers—especially for downhill—usually go well into your 30s, and longevity is really important if you want to succeed as any professional athlete; it just builds on itself. But it can be a bumpy road. I have dealt with some serious setbacks, but my education allows me to continue to pursue my skiing goals, knowing I have other options. I’m grateful Dartmouth’s Thayer program has enabled me to pursue both engineering and skiing.”

Patrick O’Brien ’10

Cross-country skiing

Putney, Vermont

Environmental studies major, geography minor

8th, 2013 USSA Distance National Championships; 6th, overall, 2013 USSA SuperTour ranking

“There’s so much momentum in cross-country skiing in the United States right now. In that sense the competition is cutthroat, but it’s encouraging to see that the sport is growing nationally. I would love to go to the Olympics, but even if I don’t I’m happy to know that the bar has been raised in our sport in the United States.”

Eric Packer ’12

Cross-country skiing

Anchorage, Alaska

Engineering (Phi Beta Kappa)

7th, freestyle sprint, 2013 U.S. National Championship; 3rd, classic sprint, 2012 National Championship; three-time NCAA All-American

“My approach to getting to the Olympics is focusing on the process and not on the results—on doing everything right along the way in order to make sure that when I show up on race day, I’ll be as prepared as possible. This is certainly something I learned at Dartmouth. If you focus on all the little things along the way in the process of excelling in a course, developing relationships with a professor or anything else, the results will show by themselves.”

Ida Sargent ’11

Cross-country skiing

Barton, Vermont

Biology major, psychology minor

U.S. Nordic “A” team since 2010; five top-10 finishes, 2013 World Cup; 4th, U-23 2011 World Championship

“Dartmouth helped me to balance skiing with academics, and I’m still seeking balance in my life. Recently I’ve been doing a lot of Rosetta Stone to keep my brain from rotting. Competing in the Olympics is something I always thought about. It’s a really exciting time for me because it’s finally coming together.”

Sophia Schwartz ’13

Freestyle mogul skiing

Sun Valley, Idaho

Neuroscience major, biology minor (expects to graduate in 2016)

U.S. Mogul Ski Team; winner, 2013 U.S. Freestyle Dual Mogul Championship; winner, 2013 Nor-Am Cup events, Telluride, Colorado, and Apex, Canada

“At first I was nervous that it would be hard to meet people at Dartmouth, since I would be gone for skiing so often. But luckily I’ve found a home in the ultimate Frisbee team. It’s a very warm and proactive community on campus. With other friends pursuing LSAs and off-term internships, I don’t feel unique when I come back to campus after skiing.”

Michael Sinnott ’07

Cross-country skiing

Sun Valley, Idaho

Psychology major, neuroscience minor

Overall champion, 2013 USSA SuperTour; silver medals, 2013, 2012 and 2011 U.S. Cross-Country championships

“My junior ski coach told me I would have a great time anywhere, but that I should find a place that fit me. Dartmouth people just fit with me. There’s an intensity and excitement and happiness about Dartmouth students. Every single person has passion of an incredible caliber. The idea and task of trying to be great without it becoming overwhelming—this is what I found to be the unifying force of the people that I encountered and enjoyed at Dartmouth.”

Trace Cummings Smith ’15

Alpine skiing (Estonia)

Dedham, Massachusetts

Economics major, government minor

Estonia Alpine Ski Team; 36th, 2013 World Championship; two top-10 finishes, 2013 EISA races

“I skied for the United States when I was younger but had the opportunity with dual citizenship to change the country for which I compete. I can represent Estonia on the world stage, which is a really cool thing. It’s definitely a part of my family’s past that I’m proud of. On the alpine side of the Estonian ski federation there are only a couple of guys who are competing at a really high level vs. about 50 guys in the States. Estonian skiers don’t really train together. We’re on our own.”

Sara Studebaker ’07

Biathlon

Boise, Idaho

Government/International relations major, Latin American, Latino & Caribbean studies minor 2010

U.S. Olympic team (34th in Vancouver); U.S. Biathlon Team since 2007; U.S. World Championship team, 2011, 2012 and 2013; 15th, 2012 World Cup, Kontiolahti, Finland; 14th, 2011 World Cup, Presque Isle, Maine

“Going to the Olympics the second time, I’m a lot less nervous. In 2010 I was in awe. Dealing with that level of pressure and attention from the media was all very new. Now I think I can focus on the race and compete better than I have ever before. Confidence is really key.”

Sam Tarling ’13

Cross-country skiing

Cumberland, Maine

Environmental studies major, geography minor (expects to graduate in 2014)

2013 U-23 World Championship team; 2013 national training group; 3rd, 2012 NCAAs; winner, 2011 NCAAs

“I loved the day-in-and-day-out at Dartmouth, showing up to practice and training. It might not seem special or fancy, but those workouts were really important to me. I’m the age of the ’12s, the class of the ’13s and am graduating with the ’14s. Being committed to skiing, I’ve had to space my academic courses out. Thankfully I have enjoyed all of my classes. I’m very interested in environmental studies and plan to work with GIS mapping software.”