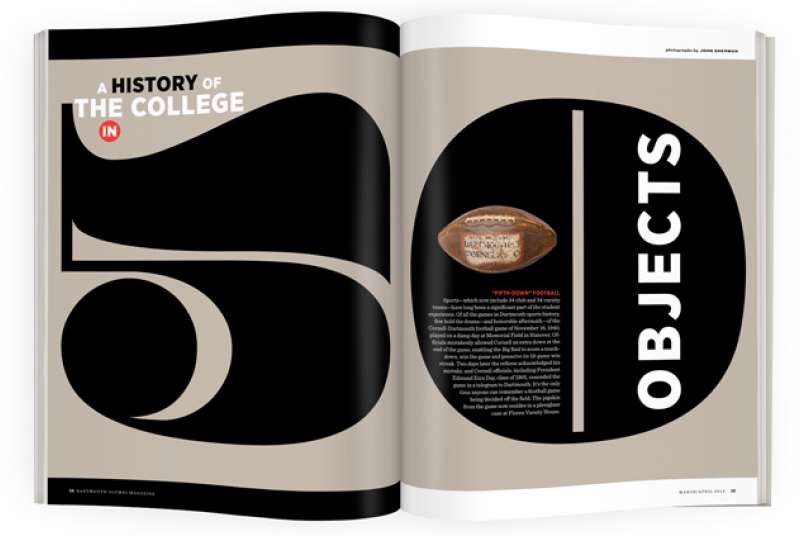

A History of Dartmouth in 50 Objects

You can click here to view a photo gallery of all the objects.

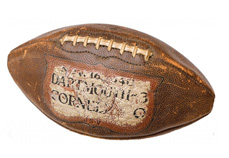

“Fifth-Down” Football

“Fifth-Down” Football

Sports—which now include 34 club and 34 varsity teams—have long been a significant part of the student experience. Of all the games in Dartmouth sports history, few hold the drama—and honorable aftermath—of the Cornell-Dartmouth football game of November 16, 1940, played on a damp day at Memorial Field in Hanover. Officials mistakenly allowed Cornell an extra down at the end of the game, enabling the Big Red to score a touchdown, win the game and preserve its 19-game win streak. Two days later the referee acknowledged his mistake, and Cornell officials, including President Edmund Ezra Day, class of 1905, conceded the game in a telegram to Dartmouth. It’s the only time anyone can remember a football game being decided off the field. The pigskin from the game now resides in a plexiglass case at Floren Varsity House.

Senior Cane

Senior Cane

The tradition of customized senior canes began when A. Herbert Armes, class of 1885, asked his friends to carve their initials in his walking stick before graduation. This evolved to more elaborate carvings, and in the late 1890s Charles Dudley, class of 1902, designed this popular Indian head cane. Commercial production and a patent on the design followed, and Dudley’s design became the most common cane carried by seniors. These days you’re likely to find more canes carved with a cobra or sphinx than an Indian head: Members of various senior societies carry such canes at Commencement as symbols of their organizations.

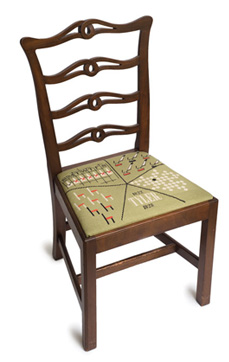

Presidential Seat Cushion

Eighteen presidents have served the College, but only after they retire do they attain a true seat of power at the president’s mansion. Sixteen custom seat cushions adorn the chairs used in the dining room there, each representing a past president. (Jim Kim’s is currently in the works.) The cushion of Bennet Tyler, president from 1822 to 1828, symbolically depicts (clockwise from upper left quadrant) his discontinuation of daily chapel, his four years in the red and two in the black, the admission of the College’s first black student and an increase in the number of professorships during the Tyler administration. The cushions originated in 1958, thanks to an idea from College designer John Scotford ’38, needlework by descendants of John Sloan Dickey ’29, among others, and chairs crafted in the student woodworking shop. Scotford also designed the Dartmouth flag.

Queen of the Snows Tiara

Can a monarch be a monarch without being crowned? At Dartmouth the answer was yes—from 1923 to 1946. In 1947, however, this dazzling headgear was presented to the weekend date chosen as Winter Carnival Queen of the Snows, a tradition that lasted 50 years, until coeducation began. The queen was selected annually from a bevy of candidates marching in the Carnival’s midnight costume parade, and presentation of this silver-and-stainless-steel tiara, which makes Miss America’s look like a mere headband, formalized the title. Winners need not possess talent, noted one observer, only “a beautiful face and a good costume.”

Wood and Canvas Canoe

Wood and Canvas Canoe

“The canoe continues to link generations of Dartmouth students; to evoke something true and essential about the College,” wrote Jim Collins ’84 in this magazine 10 years ago. “I hope the canoe will endure as a symbol of Dartmouth, not just for what it is but for what it says about the character of our students.” From the exploits of John Ledyard, class of 1776, who canoed his way out of Hanover more than 200 years ago, to his namesake Canoe Club, which hosts the annual Trip to the Sea in his memory, paddling on the Connecticut River has always been part of the Dartmouth experience. This 1950s-era canoe belongs to head of outdoor programs Dan Nelson ’75.

Piece of Wood from Molly Blackburn Hall

When student-built shanties on the Green were destroyed in the early morning hours of January 21, 1986, Dartmouth found itself in the national spotlight. The protest over College investments in companies operating in South Africa featured one shanty named for the anti-apartheid activist; a piece of that structure, above, is held in Special Collections. Although President David McLaughlin ’54, Tu’55, had determined that the shanties—erected the previous November—could remain on the Green as long as they were “educational,” a group of 12 students (nine were staffers at The Dartmouth Review) calling itself the Dartmouth College Committee to Beautify the Green Before Winter Carnival demolished three of the structures with sledgehammers, claiming they had been built illegally. One shanty, occupied by sleeping students, was left standing. In the wake of coverage that decried the incident as an example of racism at Dartmouth, the College suffered a 25-percent drop in applications from black students for the class of 1990. Not until 1989 did the College divest itself of holdings in South Africa.

Black Ball Box

Black Ball Box

Greek life has been a staple of the student experience at Dartmouth since 1841, an outgrowth of the student literary societies of the late 1700s and early 1800s. With 16 fraternities, 9 sororities and 3 coed houses, the College offers many choices for those inclined to join—which more than 60 percent of eligible students do. But not everyone gets into the house they desire. Conceived as an anonymous means of dinging or admitting potential members, and as a way to perpetuate houses’ exclusivity, boxes such as this one belonging to Delta Kappa Epsilon were common. Placing a white ball in the covered box signified a “yes” vote; black signified the opposite. The term “blackballing” originates from this practice. Today members of sororities and fraternities vote on new members in a variety of ways that no longer involve the use of boxes.

Wheelock’s Conch Shell

Dartmouth founder Eleazar Wheelock brought this ocean artifact with him to Hanover, where it was used as a horn. When students heard its call they came running, as glorified in a 19th-century College song by E.E. Parker, class of 1869, and Addison Andrews, class of 1878: “It called the students from their play, to work, to prayers, with potent spell; Ill fared he who dared disobey the summons of the Old Conch Shell.” Freshmen were tasked with blowing the conch horn, but some were better than others. When the job fell to John Ledyard, class of 1776, he sounded the call with “reluctance and in a manner corresponding to his sense of degradation,” according to College historian Frederick Chase, class of 1860.

Robert Frost’s Suitcase

Robert Frost’s Suitcase

Rauner Library houses 1,500 items in its Frost collection, one of the largest and richest in the world. It includes 44 of Frost’s 48 surviving notebooks, 2,000 images and a large body of correspondence and manuscripts. After Frost, class of 1896, died in 1963, his longtime secretary delivered a number of his manuscripts to Dartmouth’s Special Collections library in this suitcase, which features the poet’s initials in gold above the handle. One of the College’s more famous alumni—and dropouts—Frost won four Pulitzer prizes before returning to Dartmouth in 1943 as a guest lecturer and resident poet. He is the only person to receive two honorary degrees from the College.

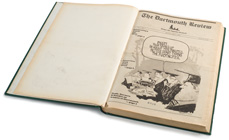

The Dartmouth Review

Say what you like about its brand of provocation (and we know you will), for more than a quarter century the student paper has undoubtedly been the most controversial conservative newspaper in the Ivy League. “The editors of The Dartmouth Review have been a public embarrassment, willfully so, to the good name of Dartmouth’s liberal administrators, faculty and trustees,” according to a 2006 history of the publication. No kidding. The first issue rolled off the presses in June 1980, and still publishes—somewhat erratically—to always polarized reviews.

Vintage Wooden Skis

Vintage Wooden Skis

When America’s interest in skiing took hold in the 1930s, Dartmouth was well ahead of the curve. Students organized ski trips in the 1880s, and in 1896 they started a “skee” club. The 40-meter ski jump built in 1921 was the biggest in the East. The first overhead-cable ski lift in North America was built on Oak Hill, and in 1956 the Dartmouth Skiway opened. The ski jump is now gone, but its former location on the golf course doubles as part of a cross-country ski center in the winter. Small wonder, then, that the College has sent a skier to every Olympics since 1924, with more than 40 student and alumni skiers having competed since then.

John Rassias’ Egg

Egg-cellence in teaching? For the fifth consecutive year Dartmouth has earned the top spot for “Strong Commitment to Teaching” and remains in the top 10 national universities in U.S. News & World Report’s “Best Colleges 2014.” The faculty’s commitment to teaching is exemplified by legendary professors such as John Rassias, the father of the Rassias method of language instruction. “The air [in his] classroom is filled with more than French adjectives. Very often there are flying desks or eggs or raw meat,” wrote an Associated Press reporter in 1978. “If I’m animated as a teacher then my students will be animated,” the professor explained to the reporter. “If I get up there and sleep, they will sleep.” A signature part of the Dartmouth experience, says dean of the faculty of arts and sciences Michael Mastanduno, “is to take extraordinary undergraduates and give them close, working access to a faculty that is both dedicated to teaching and mentoring and distinguished in research.” More recently, President Phil Hanlon ’77 expressed his commitment to undergraduate teaching excellence during his first major address to faculty last November.

Webster’s Top Hat

Webster’s Top Hat

Daniel Webster, class of 1801, was the original cat in the hat when he donned this beaver-fur top hat custom-made for him in Boston in 1852. A famous orator, Massachusetts senator and U.S. statesman, Webster failed to win the presidency as a candidate three times, but he argued more than 200 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and won about half of them. In Dartmouth College v. Woodward in 1819, he argued for nearly four hours in front of the justices, ending his presentation with perhaps the most famous words in Dartmouth history: “It is, Sir, as I have said, a small college, and yet there are those that love it.” He won the day, ensuring that his alma mater did not become a public university. Webster’s name appears across the campus, and Rauner Library’s vast Webster collection includes his hat, silk socks, a hat rack made of antlers, and his open carriage.

1894 Faculty Report on Coeducation

Women had to wait a long time before gaining College acceptance. A faculty committee favored coeducation 120 years ago, following a debate over interpretations of the terms “English youth and others” in the College charter. A penciled dissent, signed by professor J.B. Richardson, seems to have halted the idea. In 1963 faculty and students petitioned for the admission of women, leading to—of course—the formation of another committee. As is often the case in higher ed, things took a while. Trustees finally allowed women to matriculate in 1972.

Dartmouth Cup

Dartmouth Cup

The ninth earl of Dartmouth brought this ornamental silverware to campus in 1969 as a gift to the College during its bicentennial. Made in 1848 by a company that made fine silver for British royalty, it was purchased by the fourth earl of Dartmouth, then passed along. Since 1983 the College usher—usually the dean of libraries—carries the cup at Commencement to honor the College’s namesake.

Wentworth Bowl

John Wentworth, royal governor of New Hampshire, presented College founder Eleazar Wheelock and “his Successors in Office” a silver bowl intended to mark Dartmouth’s first commencement in 1771. Due to delays in its production in Boston, however, the silverware didn’t arrive until the second graduation ceremony. One of only three known colonial-era silver monteiths, this symbol of the Dartmouth presidency is passed from president to president during inauguration ceremonies. It has also seen less-glamorous duty, serving as a punch bowl for events at the President’s House.

Flude Medal

Flude Medal

In 1785 a London pawnbroker named John Flude, about whom little is known, gave a medal to College President John Wheelock, class of 1771. Its origins remain a mystery—it might have been pawned by one of Flude’s customers and never redeemed. Engraved on the medal are the words “Unanimity is the Strength of Society” and a depiction of one of Aesop’s Fables, “The Old Man and His Sons.” The meaning is unclear, but no matter: Dartmouth’s president wears the Flude Medal as part of his academic regalia during ceremonies such as inauguration, convocation and commencement.

College Seal

The first order of business for College trustees at their August 1773 meeting was to vote on a Dartmouth seal. Today its designer remains unknown, although speculation abounds that founder Eleazar Wheelock drew it up. “The result is a piece of late-colonial kitsch,” according to an article about the seal’s history that appeared in the Dartmouth College Library Bulletin in 1997. In 1957 someone noticed a major error on the seal: It featured the year 1770, as shown in the die above, but the College was founded in 1769. This led to the formation of a committee and much hand-wringing before it was decided to fix the date with a new version of the seal. For official use only, it is not the same seal as the one commonly found on T-shirts and stationery. That is a simplified version that came out in the mid-20th century.

Edward Tuck’s Pocket Watch

Edward Tuck’s Pocket Watch

This Tiffany timepiece, an 1886 gift from his wife, Julia Stell Tuck, could easily have been lost in the deep pockets of its owner, a member of the class of 1862. Tuck, one of the most generous alumnus of all time when his gifts across 40 years are adjusted for inflation, donated $300,000 to endow a business school named for his father, Amos, class of 1835. In 1900 the Tuck School of Business opened its doors as the first such graduate school in the country. The significance of Tuck’s generosity was frequently noted in The New York Times, which wrote of his underwriting of faculty salaries, Tuck Drive, the President’s House and much of the rebuilt Dartmouth Hall.

Nails from Dartmouth Hall

Out of the ashes of the burning of Dartmouth Hall in 1904 came these handmade nails—and a whole new sense of urgency in alumni giving. After the fire Melvin O. Adams, class of 1871 (and famous for his defense of ax murderer Lizzie Borden), appealed to Boston-area alumni for reconstruction money. “This is not an invitation,” he wrote. “It is a summons.” As a result, alums raised $100,000 to rebuild. The successful campaign was the culmination of a decade of alumni cultivation by President William Jewett Tucker, class of 1861. The College rode this wave of alumni support into the modern era by starting three new alumni ventures in three years—the Association of Class Secretaries, the predecessor to the Alumni Fund, and the alumni magazine. Today among Ivy schools, only Princeton (61 percent) leads Dartmouth (49 percent) in participation rate of alumni giving.

Occom’s Diary

Occom’s Diary

Samson Occom was a reverend and Mohegan Indian who studied theology under Congregational minister and Dartmouth founder Eleazar Wheelock. In 1766 and 1767 Occom traveled to Great Britain to solicit money for Wheelock’s Indian Charity School, a predecessor to Dartmouth College. His diary details the 18-month trip, during which he delivered between 300 and 400 sermons—and raised 12,000 English pounds for Wheelock’s school. His legacy remains in Occom Pond, Occom Ridge, Occom Commons of the McLaughlin dorm cluster, and the Samson Occom Professor of Native American Studies position.

Indian Symbol Felt

In the 1920s Boston sports writers nicknamed Dartmouth sports teams “the Indians.” This felt prototype, created in 1932 by Walter Beach Humphrey, class of 1914, was one of several unofficial mascots used for years. It made its way onto everything from neckties and T-shirts to key chains and other knickknacks. Humphrey, who found fame as an illustrator, also painted the politically incorrect Hovey murals in Thayer dining hall in the late 1930s. In 1972 the trustees declared the use of the Indian symbol “in any form to be inconsistent with present institutional and academic objectives.” (The murals have been covered since 1983.) The banning spawned outrage as many alums clung to their old symbol for years.

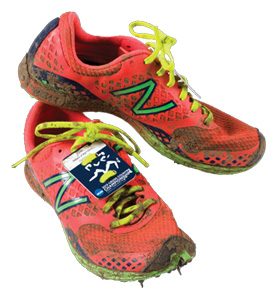

Abbey D’Agostino’s Racing Spikes

Abbey D’Agostino’s Racing Spikes

D’Agostino ’14, perhaps the greatest female athlete in Dartmouth history, wore her size 7 New Balance spikes at the 2013 NCAA Cross Country National Championship, where she won it all by running a 6-kilometer course in 20:00.3. The shoes were only a week old for the event—a coach overnighted them to D’Agostino between regionals and nationals after she realized one of her older shoes had developed a hole. The most decorated student athlete in Ivy League history, D’Agostino has won five national championships and has the most individual titles of any Ivy League student athlete in any sport. In 2013 alone she won four championships, two more than any other Ivy League track athlete has ever won in a career. She’s the latest in a long line of female athletes since the arrival of coeducation in 1972. Aggie Kurtz launched five teams that year, all on a budget of $500: field hockey, squash, basketball, tennis and lacrosse. “We had limited money so we were given the choice of uniforms or equipment,” says Ann Fritz Hackett ’76, a member of the inaugural field hockey and tennis teams. “We used the money for equipment. The field hockey team was the most motley-looking crew. We all had to wear white tennis skirts—of course, none of them matched.” Women now participate in 16 NCAA Division I women’s sports and on two coeducational teams.

Freshman Beanie

Although the derivation of the word “beanie” is debated—it’s either a nod to “bean” as slang for head or a reference to the felt-covered button atop gathered triangles of fabric—the iconic cap was variously viewed as a charming or annoying tradition, an invitation to haze freshmen or a means of identifying fellow classmates. Until 1967 wearing one was mandatory for freshmen for part of the school year—unless first-year students won the annual tug-of-war against upperclassmen on Dartmouth Night. Freshmen in 1963 burned their beanies that night, perhaps signaling the looming end of the tradition.

Time-Sharing Punch Cards

Time-Sharing Punch Cards

Computing pioneers John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz designed the Dartmouth Time Sharing System (DTSS) and the BASIC programming language to be “very easy to learn” because they wanted students beyond the math and science departments to use computers. At its peak, DTSS, which ran from 1964 through 1999, depended on punch cards such as these to host 300 simultaneous users. It was the first successful time-sharing system ever. The work of Kemeny and Kurtz put Dartmouth in the forefront of computer access and networking technology through the 1980s.

Pong Paddles

Whether the game of beer pong originated at Dartmouth is debatable. That just about every student in recent memory has played the drinking game isn’t. Remember: It’s not really Dartmouth pong unless you break the handles off your paddles.

Copper Horn

Copper Horn

In the latter half of the 19th century students didn’t suffer in silence when professors doled out less-than-glowing grades. As many as 200 masked students would vent their ire by assembling outside a prof’s home at night to blow copper horns and toss rocks at windows. President William Jewett Tucker demanded an end to the practice in 1896, when he expelled 10 students for “horning” and forced students to sign an agreement to end what he called “clumsy, ungentlemanly” behavior.

Plea to Admit Edward Mitchell, Class of 1828

A group of students wrote the board of trustees after it refused to accept Edward Mitchell. Mitchell had been admitted to the freshman class by the faculty, but the board rejected his admittance. C.D. Cleveland, class of 1827, was a dark-skinned Caucasian who argued on Mitchell’s behalf, saying that if skin color excluded Mitchell from the College, then Cleveland himself would not have been admitted. The trustees reconsidered their decision, and Mitchell was admitted to the College in 1824, 40 years before any other Ivy admitted a black student. He became the first black graduate of Dartmouth.

Elm Tree Leaf

Elm Tree Leaf

Images and drawings dating back to 1840 depict the Green edged with a magnificent canopy of American elm trees, earning Dartmouth the nickname “The College of a Thousand Elms.” But the trees’ close proximity to each other led to disaster when Dutch elm disease arrived in the 1950s. The College cut 11 diseased elms in 1951, and by the 1980s Dartmouth had lost more than 200 elms. Roughly 150 remain on campus and town streets. Last year a 140-year-old giant elm succumbed to root rot, and the Collis elm was taken down in 2012 because of decay in the trunk. In 2011 the Parkhurst elm was also removed due to an insect infestation. Since the 1990s the oldest elms have been treated with preventive fungicide injections, and several dozen young, disease-resistant elms are added to the College’s tree nursery each year. According to campus arborist Brian Beaty, Dartmouth continues to plant elm trees because, in addition to their historical significance, desirable form and superior architecture, American elms are usually tolerant of urban growing conditions.

Swatch of Green Silk Grosgrain Ribbon

“Green was adopted as the Dartmouth color at a mass meeting of students held in the Old Chapel in the autumn of 1866 at the instance of a group of seniors. This sample is from the original ribbon selected to establish the shade of green,” reads the inscription on the framed piece of the remnant, now housed in Rauner Library. Although the inscription suggests green was an inspired choice, in reality it was the fallback option. “Indeed, it was the only decent color not taken already,” wrote Frederick G. Mather, class of 1867.

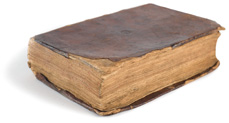

Wheelock’s Fulfilling of the Scripture

Wheelock’s Fulfilling of the Scripture

Before Eleazar Wheelock started Dartmouth College he was a formidable itinerant minister who greatly helped propagate the Great Awakening, an American religious revival of the 1730s and 1740s. His personal copy of Fulfilling of the Scripture, published in 1743 and inscribed with his signature on the last page in 1766, is part of the Wheelock collection at Rauner Library. The founder, who died in 1779, is buried on campus in the Dartmouth cemetery, where his epitaph reads, in part: “By the Gospel he subdued the ferocity of the savage, and to the civilized he opened new paths of Science. Traveler, go if you can and deserve the sublime reward of such merit.”

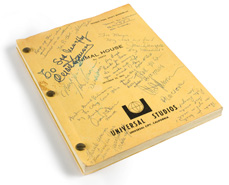

Signed Animal House Screenplay

There’s no need to wonder which movie is the most reviled by Dartmouth administrators. The 1978 comedy Animal House, penned in part by Chris Miller ’63, based many of the onscreen shenanigans on Miller’s days at Alpha Delta. Right or wrong, to this day the reputation of the College remains inextricably entwined with the screwball farce. A screenplay autographed by the cast and crew—including Karen Allen, director John Landis and self-described “Head Animal” John Belushi—found its way to Special Collections a few years back. It was originally owned by a policeman who helped keep Belushi out of trouble while filming the classic in Oregon. Whomever obtained it without permission of the administration has been on double-secret probation ever since.

Sealed Files

Sealed Files

In 2003 President Jim Wright decreed a new institutional records policy that keeps plenty of recent history under wraps for decades. Anything created by the board of trustees and all corresponding documents remain sealed for 50 years after the date of creation. Presidential records receive the same treatment, but only for 25 years after an administration ends. Relevant files are boxed in Rauner and sealed with a little sticker that reads: “Record of the Board of Trustees: Restricted for 50 years from date of creation.”

Lone Pine

Nothing symbolizes Dartmouth’s history, mythology, poetry and traditions better than the Lone Pine (originally known as the Old Pine). The tree—which stood on the hill behind the observatory—became known as a gathering place for graduating seniors by 1828. Around the same time stories circulated about American Indians singing at the same spot. It became the location of Class Day in 1854. After suffering damage in an 1887 lightning strike and an 1892 windstorm, the tree was cut down in 1895. Experts counted rings and dated it to 1783. This remnant is kept in a locked storage room at Special Collections. The pine’s reputation continued to grow posthumously: It was admitted into the American Forestry Association National Hall of Fame in 1922 and was cited by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a “Famous Tree” in 1938. In 1967 the class of 1927 planted an homage to the Lone Pine: This Dartmouth Pine grows at the entrance to the Bema.

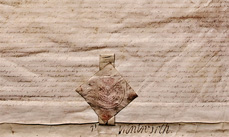

College Charter

College Charter

Handwritten on two large sheets of vellum, the charter founded Dartmouth “for the education & instruction of Youth of the Indian Tribes in the Land…for civilizing & christianizing Children of Pagans….” College founder Eleazar Wheelock drafted the charter, though the original version incorrectly spells his name “Eleazer.” Royal Governor of the Province of New Hampshire John Wentworth granted the charter on December 13, 1769, making Dartmouth’s the ninth and last royally granted charter before U.S. independence. The charter also holds legal significance. In the 1819 U.S. Supreme Court case Dartmouth College v. Woodward, the New Hampshire legislature attempted to force the College to become a public institution. The Supreme Court ruled to uphold the charter, thanks in part to a compelling argument by Daniel Webster, class of 1801.

Baker Tower WeatherVane

Early architectural sketches of Baker Library included a generic weathervane. President Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, ordered that it incorporate a Dartmouth theme. Library architect Jens Fredrick Larson asked his assistants to compete for a final design. The winner, Stanley Orcutt, was given a Dunhill pipe. His design hit all the high points of Dartmouth iconography—the founder, the education of American Indians and the Lone Pine. Made of copper, the weathervane was made in 1928 by A.N. Merryman of Maine. It is nearly 9 feet long, stands 6 feet 8 inches high and weighs 600 pounds.

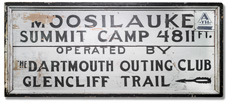

Mount Moosilauke Trail Sign

Mount Moosilauke Trail Sign

Dartmouth’s connection with Mount Moosilauke began with an alumni donation. The owners of the hotel at the mountain’s summit, E.K. Woodworth, class of 1897, and Charles Woodworth, class of 1907, gave the property to the Dartmouth Outing Club in 1920. Additional donations brought the College’s total holdings on the mountain to 4,537 acres, making it the largest privately owned tract inside the White Mountain National Forest. Today nearly all freshmen are introduced to Dartmouth’s traditions via freshman trips that culminate at the mountain. This old trail sign, circa 1920, now hangs at the Canoe Club restaurant in Hanover.

Sundial

A surveyor named Samuel Holland gave Dartmouth its first scientific instrument. The sundial stood on a post in front of the Wheelock mansion (where Reed Hall stands today) from 1773 until the 1850s, greeting every visitor to the College coming up from the river. Many of those visitors were likely setting their pocket watches to match the only precision dial in western New Hampshire. Richard Kremer, a professor of the history of science, considers the sundial “one of the central icons of natural philosophy at Dartmouth.” It’s on display at the Fairchild Center.

Warner Bentley Bust

Warner Bentley Bust

Decades of students have rubbed Bentley’s nose for good luck, removing its brown patina to reveal the bronze underneath. Much more was revealed when a 1996 April Fool’s prank involving tarnish remover stripped the patina covering the rest of the statue. Kellen Haak ’79, then registrar at the Hood Museum of Art, painstakingly restored the statue with a Q-tip, calling it a “labor of love, having rubbed Warner’s nose on more than one occasion as an undergraduate.” Bentley was a professor of English, the first director of the Hopkins Center and director of the Dartmouth Players. During his 41 years at Dartmouth he oversaw the creation of the Hopkins Center for the Arts. The bust was commissioned by the College trustees, sculpted by artist-in-residence Thomas Bayliss Huxley-Jones and presented to Bentley at his

retirement party in 1969. It rests on a pedestal at the Hopkins Center.

Outing Club Pin

Fred Harris, class of 1911, in 1909 started the nation’s first collegiate outing club, establishing Dartmouth’s reputation for embracing the outdoors. By 1917 more than 700 people had joined, and some of them helped launch similar clubs at Yale, Tufts, Colgate and the University of Vermont. Few schools, however, boast the outdoor resources here: a downhill ski area, a ski-touring center, 4,800-foot Mount Moosilauke, the Ravine Lodge, the Second College Grant with its 19 cabins and eight shelters, a canoe club, three ropes courses and the Appalachian Trail running through the center of campus. The club distributed pins from 1936 to 1954, and a collection of them can be found in Special Collections.

Orozco Murals

Orozco Murals

José Clemente Orozco first came to Dartmouth for a two-week stay in 1932 under a newly established artist-in-residence program. After catching sight of “the walls of my dreams” in the Baker Reserve Reading Room, Orozco drafted a letter to President Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1901, proposing the history of the Americas as the topic for a 14-panel fresco, The Epic of American Civilization. Hopkins agreed, and Orozco spent the next two years on the murals, for which he was paid approximately $7,000. The artist, who lost his left hand to fireworks as a child, relied on assistants and a plasterer to help him create the masterwork, named a national historic landmark in 2013. At right, the Anglo-America portion of the murals that depicts what a Hood Museum brochure describes as a “tall, stern-faced schoolmarm.”

Halden Calculex Circular Slide Rule

This intricate measuring device, three inches in diameter, belonged to Robert Fletcher, the first director and dean of Thayer School of Engineering. He was also the only Thayer instructor for five years. Founded in 1867 by Brig. Gen. Sylvanus Thayer, class of 1807 and the so-called “Father of West Point,” the school was originally known as the Thayer School of Civil Engineering. The school has grown from its first class of three students to a current enrollment of more than 350, thanks in part to the building of its own facility in 1938.

Broken Clay Pipes

Broken Clay Pipes

The Class Day tradition of smoking clay “peace pipes” before smashing them on the Lone Pine stump began in the 1880s. It ended in 1992 because the tradition was seen as offensive to Native American students, who explained that the pipes were considered sacred objects in their culture. In 1993 the tradition was revived, somewhat, with students drinking a toast from clay mugs before smashing them at the base of the Lone Pine. Several students suffered injuries and required stitches when they were bombarded with shards of the clay cups. Nowadays, students simply hold a candlelit vigil with no pipes, mugs or smashing of any kind.

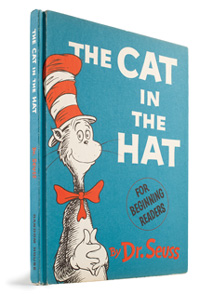

The Cat in the Hat

Theodor Seuss Geisel ’25 wrote The Cat in the Hat in response to a challenge to write a book using only a list of 348 words deemed important for first-graders to recognize. The book contains 236 of the words. This first trade edition, published by Random House in 1957, was an instant success, and more than 10 million copies—in 12 languages—have been sold since, making it one of the most recognizable from the Seuss canon. The prolific author, one of the College’s more favored sons, has sold more than 600 million books overall but never let his popularity go to his head. “My animals look the way they do because I never learned to draw,” he once admitted. In 1955 Dartmouth legitimized the “Dr.” in his pen name by awarding Geisel an honorary doctorate. And in 2012 Dartmouth renamed its medical school “The Audrey and Theodor Geisel School of Medicine.”

Peavey Head

Peavey Head

In 1806 the College was on the ropes financially. Former New Hampshire congressman and Dartmouth trustee Jonathan Freeman lobbied the state to grant Dartmouth 27,000 acres in the northern part of the state. Trees, not crops, were the Second College Grant’s economic engine. For more than a century the harvesting of softwoods brought in cash. Around 1930 the College began managing the land for selective cutting and multiple uses, which continues at the Grant under the management of forester Kevin Evans. He found this logging tool, dating to the 1850s and used to slide or rotate large logs, in Squeeze Hole Brook 13 years ago. When he stopped to take a break while laying out a clearcut, he looked down and there it was. Evans estimates the Grant pumps about $700,000 into the North Country economy, providing jobs to about 20 local contractors. The Grant is also valued by students and alumni as a place for research, hiking, hunting and camping.

First Medical X-Ray

Hanover local boy Eddie McCarthy slipped into medical history by breaking his wrist while skating on the Connecticut River. Several days later, on February 3, 1896, the fracture was immortalized in the first medical X-ray. The experiment, an early example of Dartmouth’s interdisciplinary approach to research, took place in the physics lab, where professors from the Medical School, Thayer School and the astronomy department proved the diagnostic potential of the X-ray. The exposure lasted 20 minutes and revealed a fractured ulna.

Campaign Buttons

Every four years students get a up-close look at presidential politics when the New Hampshire primary brings White House wannabes to Hanover. The first modern primary in the state was held in 1952. Since then the College has also hosted nationally televised debates. The first was held in 1984, and the most recent—for Republican candidates—in October of 2011.

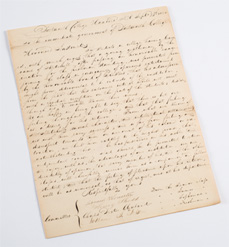

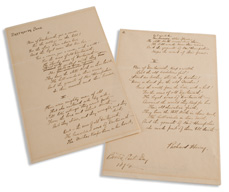

Revised “Men of Dartmouth” Poem

Revised “Men of Dartmouth” Poem

The wording of the alma mater has been in flux since the beginning, as indicated by a copy of the lyrics originally created by Richard Hovey, class of 1885. Dated “Boston, Easter Day 1894,” it shows some of the author’s handwritten changes. For example, he crossed out part of the line: “For burning altar-flame” and penciled in “And guards their altar-flame.” The words eventually became the alma mater after Harry Wellman, class of 1907, put them to music in 1910. When women arrived in 1972 a kerfuffle ensued over the opening words, “Men of Dartmouth,” which had also become the title of the song. Protests, committee meetings and another row over the old vs. the new ensued until 1988, when the song became known simply as “Alma Mater” and the opening words were changed to “Dear old Dartmouth.”

Keggy

An unofficial mascot conceived by Nic Duquette ’04 and Chris Plehal ’04 during their senior year, the world’s most famous anthropomorphic beer keg has made a variety of campus appearances since then, from football games to mingling with voters on the Green during presidential debates, all to mixed reaction. His schedule is unpredictable: Just when you think he’s gone for good, Keggy arrives on the scene to stir things up. “Some people think I’m a bad influence,” he told DAM in a 2004 interview. “I’m poking fun at Dartmouth’s ineptitude at finding a mascot.” The barrel-chested beer dispenser also scoffed at the notion that he was an imbiber. “Drinking beer would be cannibalism,” Keggy explained.

Senior Fence

Senior Fence

Construction of the Senior Fence had nothing to do with seniors. It was built to keep cattle off the College-owned Green. By 1893 free-range cattle were no longer a concern. Students responded to plans to dismantle the fence by asking that a portion be left intact. They were adamant that fence sitting was a seniors-only perk. Here, seniors carve their canes on the fence circa 1900. Underclassmen caught on the fence were dunked in a water trough. In response to changing community standards (and the lack of a water trough), anyone can now loiter on the fence, which runs along the southwest corner of the Green.