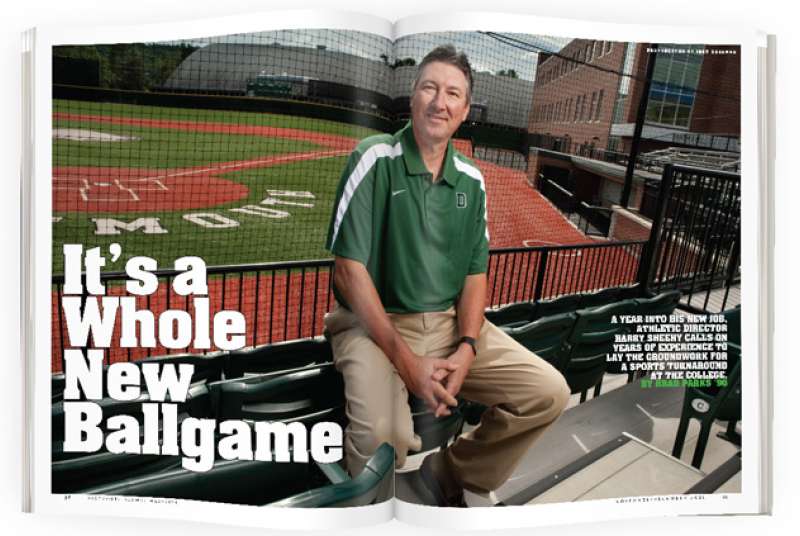

It’s a Whole New Ballgame

The kid was already walking down the hill, in plain sight. Harry Sheehy, then a 31-year-old first-year basketball coach at Williams College, didn’t care. He had told the players the bus was leaving at precisely 1 o’clock. He had warned them he was a stickler for time. And it was now 1. He told the driver to pull out.

The kid started running. The driver asked if he should stop. No, Sheehy told him, keep going.

The kid borrowed a car, one that belonged to a woman he had been dating for all of a week. The kid followed the bus for three hours—through a blizzard, no less—up to New England College in New Hampshire. The kid dressed for the game, went through warm-ups, sat in on the pre-game talk, everything.

And Sheehy didn’t play him a minute.

“The funny thing is, I actually had my stuff on the bus,” laughs John McCarthy, the kid who graduated from Williams in 1984. “I had just run back to my dorm room to get my Walkman. Harry still left me.”

McCarthy is now the director of the Institute for Athletic Coach Education at Boston University. He teaches coaching for a living. When he needs to give his students an example of a coach having principles and sticking to them, he recalls that bus episode.

Sheehy remembers it, too.

“Like it was yesterday,” he says. “And let me tell you something else about that night. We lost by one point. It ended up costing us a tournament berth. I have no doubt that had John played we would have won. But you know what? I would do it again. I’ve always felt the lessons are so much greater than the W’s and L’s.”

Sheehy, 59, is now 28 years removed from that night. He spent 17 of those as Williams’ basketball coach, compiling a 324-104 record and taking two teams to the Division III Final Four. He logged 10 more years as Williams’ athletic director, winning 10 straight Directors Cups for having the best overall program in Division III. Now he is completing his first year as Division I Dartmouth’s athletic director.

The people who have known him all that time say he’s changed only so much. He’s still a stickler for time. He’s still got his principles. And he abides by them, no matter what. It’s the formula that helped bring him all that success at Williams. The only question echoing around Alumni Gym now: Will it work at Dartmouth?

If Sheehy had one thing going for him when he was hired in the summer of 2010, it was that he couldn’t have made things much worse. Long accustomed to success, Dartmouth athletics had fallen into dark times during the first decade of the new millennium.

It wasn’t just the football team, which hadn’t recorded a winning season since 1997. There seemed to be a malaise that spread to nearly all corners of Hanover’s fields, rinks and courts. By 2009-10 it had gotten so bad that Dartmouth’s 34 varsity sports won exactly one Ivy League title, in baseball. The four highest profile sports—football, men’s and women’s basketball, and men’s hockey—had a combined 28-67-3 record, a grim .285 winning percentage.

The common culprit cited was recruiting: Dartmouth’s academic index—a combination of class rank and SAT scores used by all Ivy League schools to determine whether an athlete can be admitted—had risen so high it was now fighting for the same student-athletes as Harvard, Yale and Princeton, and it had neither the financial aid resources nor the facilities to compete consistently.

But that was scarcely solace when popular, well-respected coaches—football’s John Lyons or basketball’s Dave Faucher, men who had successful teams throughout the 1990s—were fired after their 2004 seasons. Or when a letter from then-admissions director Karl Furstenberg leaked the same year. The administrator ultimately responsible for admitting athletes called football and other sports “antithetical to the academic mission of colleges such as ours” in a letter to the president of Swarthmore, setting off a howl of protest from alums who felt they had learned some of their best lessons from their coaches.

Sure, there was a building boom—started by athletic director Josie Harper and continued by interim athletic director Bob Ceplikas ’78—that was transforming much of the school’s physical plant, giving many sports new homes and improved practice facilities. But no one went to games to cheer for shovels and backhoes.

Don Mahler, the irascible Valley News sports columnist, put it best when Sheehy was announced as the school’s eighth athletic director: “I will tell you,” Mahler wrote, “that if the new athletic director can ever have the same success he did at Williams, he may have to change his name from Harry Sheehy to Harry Houdini.”

The man being brought in to work magic with Dartmouth athletics is a 6-foot-5 former college basketball star. But if there’s one thing important to remember about Sheehy, it’s that he didn’t start out like one. As a high school sophomore growing up on Long Island he was still 5-foot-2. As a senior he was only barely being recruited and his grades were only so-so. His father packed him off to Cranwell, a Jesuit prep school where the monks spent a year beating him into shape. He also grew several inches and suddenly had colleges interested in him. “That year,” Sheehy says, “was a miracle for me.”

He chose Williams, because that’s where his father went, and made basketball his unofficial minor, often joining his coach, Curt Tong, on scouting trips. On the court Sheehy was a small-college Larry Bird: A player with the skills of a guard but the size of a forward; a player who could score, rebound and distribute with equal skill. “His basketball IQ was off the charts,” says Fred Dittman, a former teammate and classmate. “He was brilliant in terms of understanding the game and how all the moving parts came together.”

He became the school’s all-time leading scorer, averaging 22 points a game. After graduation Sheehy had a brief tryout with the Philadelphia 76ers, then caught on with Athletics in Action (AIA), a team of evangelical Christians who barnstormed against college and international squads. He played eight years with AIA, once dropping 35 points on the Soviet Union’s national team. When Sheehy broke his ankle in his final season, he became an assistant coach. It proved to be a fortuitous move when Tong, his old coach, contacted him to say he was leaving Williams at the end of the 1983 school year.

Sheehy immediately applied for the job. He made it to the final round of interviews and was crushed when Bob Peck, Williams’ athletic director, informed him he had lost out to Reggie Minton. Sheehy flew back home, only to get a message halfway across the country that Minton had turned down the job to accept another head coaching position—at a place called Dartmouth College.

“I still have Reggie’s letter to Bob Peck framed in my office,” Sheehy says. “It’s on Dartmouth basketball stationery. That’s why I tell people I’ve always loved Dartmouth.”

Sheehy wasted little time reshaping the team. “There was this attitude at Williams that we were nice kids, we were good students and we were going to get great jobs on Wall Street someday—so who cares what we do on the basketball court?” says Dave Paulsen, who played for Sheehy at Williams, later became his replacement as head coach and now is the head coach at Bucknell University. “Harry completely transformed that culture. He wanted us to have a real lunch-pail mentality.”

Sheehy was friendly and approachable with his players, but he also didn’t spare their feelings. If a kid was soft defensively, he’d say, “You were so bad last night, Connie would have scored 20 on you.” (Connie is his wife.)

“I can remember him telling us, ‘I find for myself I’m motivated when people get on me and tell me I’m not doing a good job.’ And that’s how he coached us,” says Jim Frew, a Williams ’99. “He was good at pushing buttons.”

Despite Sheehy’s success, the grind of coaching wore on him, affecting his health and happiness. When Williams’ athletic director position opened up in 2000, Sheehy was 47. He says he applied in part because he was terrified he’d still be coaching at 65.

“My last year of coaching I went 20-4,” says Sheehy. “It was a great group of kids who played as close to their potential as any team I had ever had. It should have been one of the best years of my coaching life. Instead, all I could think about was the four [losses]. I was miserable. Finally I just said, ‘This is wacky.’ I’m coaching Division III. It’s not like they’re going to put my win-loss record on my tombstone.”

Sheehy the administrator proved to be very similar to Sheehy the coach. He was competitive. He was demanding. He was unwavering in his principles. He was successful.

And when Dartmouth came calling 10 years into his time on the job, he was inclined to decline. As a coach he had opportunities to leave Williamstown, Massachusetts, for Division I programs—Brown and Colgate—and turned both of them down. He didn’t figure this time would be any different.

“Connie and I had a great situation at Williams,” Sheehy says. “I was basketball coach and then athletic director. She was associate director of admissions. We lived in a nice house, and the checks cleared every two weeks. We were living in the same town where we both went to college. There was a lot to hold us there.”

Two conversations with President Jim Kim—one on the phone, the other in person—changed that. “I came away from those talks thinking I had a chance to do something really special at Dartmouth,” Sheehy says.

The pieces, he says, were all in place. The facilities had improved greatly under his predecessors. The institution was hungry for success after a decade of struggle. And unlike previous athletic directors, who reported to the dean of students, Sheehy would be reporting directly to the president, a man who happened to be a former high school quarterback and understood that athletics were not, in fact, antithetical to the academic mission of a college. It proved to be one of the difference-makers in Sheehy’s decision to accept the job.

“Let’s face it, who you report to in any organization matters,” Sheehy says. “And I think that was particularly important here from a symbolic point of view, because we had been coming off a pretty mediocre decade. That was one of the signs that things were going to be different.”

After accepting the new job last August he immediately set a new tone. “We are now officially in a no-whining zone,” he announced during his introductory press conference. And he made it clear he expected to win at every sport—just as he had at Williams. Everyone was on notice.

“If you polled the 30-plus head coaches here and asked them, ‘Are the expectations higher than they’ve ever been?’ The answer, across the board, is going to be, ‘Yes,’ ” says cross-country coach Barry Harwick ’77. “But then if you also ask, ‘Are you okay with that?’ The answer will be ‘yes’ as well.”

Go further and ask those same people what they think about the new athletic director and what you’ll hear is how personable, positive and energetic the guy is—and how much they like him. “Harry has taken the department by storm,” says women’s basketball coach Chris Wielgus. “He’s the right person at the right time. And the thing is, he’s not just a cheerleader. He backs it up with his own hard work.”

At his desk by 7 most mornings, Sheehy is a fixture at games played in the afternoon and evening. He runs his department meetings like team huddles, with a clear agenda and a brisk pace. And, yes, they start on time.

His first year has been a busy one, with Sheehy tackling everything from fan behavior at games to a series of new fundraising endeavors, including the endowing of several coaching positions and an increased emphasis on friends-group giving.

He’s also focused on services for student-athletes, rolling out the Dartmouth Peak Performance initiative this fall. DP2, as it’s known, focuses on all aspects of a student-athlete’s experience, from academics to training to nutrition. It not only adds new forms of assistance for varsity athletes, it also brings under one umbrella a variety of functions that had heretofore been separate—almost like adding a menu at a restaurant that never had one before, then padding it out with a few extra pages.

Although DP2 has been Sheehy’s most visible project, his coaches say his most important work has been behind the scenes, in admissions and financial aid. Sheehy knew that if recruiting woes were to blame for the College’s decade-long athletic swoon, recruiting was also the key to its recovery. This was one area where reporting directly to Kim—and Sheehy says he has open access to the president and talks to him at least once a week, if not more frequently—proved critical.

“President Kim said to me, ‘Tell me what’s in the way of success and I’ll remedy it,’ ” says Sheehy. “And [admissions and financial aid] was one area where I said, ‘Jim, here’s one that if we don’t fix it, we’ll never be successful.’ And we’ve really made some remarkable improvements in that area.”

Some of the work had been done before Sheehy came to campus, under a series of reforms instituted by admissions and financial aid dean Maria Laskaris ’84 after she took over the job in 2007. Sheehy has worked to further streamline communications. “They’ve taken some of the mystery out of it,” Wielgus says. “You used to have to wait so long to get feedback. Now they’ll look at a transcript for you a lot more quickly and at least give you some direction. That way, if it’s yes, I can go ahead and recruit a kid. If it’s no, I move onto the next one.”

Sheehy has been even more active in improving the financial aid picture. Ivy League schools cannot offer athletic scholarships, only need-based aid. But they can have surprisingly different definitions of what “need” is—and they can compete fiercely over who offers the best package. Athletes and their families often make decisions quickly, so being able to respond to another school’s counteroffer rapidly can make a difference. So is being willing to match another school’s package. And in the new Kim-Sheehy financial aid paradigm, Dartmouth has been more willing to do that.

“I’ve been here 20 years and my interactions with admissions have literally never been better,” Harwick says. “And we’ve made some extraordinary progress in the last six or seven months in financial aid. Harry’s attitude is: If a kid is considering Dartmouth, Harvard, Yale and Princeton, he’s going to make sure that kid’s family is making the decision based on something other than the cost of attending the school.”

Of course, for all the complexity of the academic index, admissions decisions and financial aid packaging, this is still sports, where the measuring stick remains quite simple: Did you win? In that area Sheehy has been the beneficiary of some immediate success that—whether he had anything to do with it—has made for a nice honeymoon. In 2010-11, 13 sports achieved national rankings, 9 appeared in the NCAA tournament and 2 (women’s lacrosse and women’s tennis) won Ivy League titles.

And, yes, the football team finally had a winning season, shellacking Princeton to finish at 6-4. For as much as Sheehy says he’s the kind of athletic director who will celebrate an Ivy League championship in field hockey just as much as he will in football, he’s also not naive about the importance of the school’s most visible program. “I have a saying to the staff that everything matters, but everything doesn’t matter the same,” Sheehy says. “There are very few places on this campus where five to eight thousand people are going to gather and all feel the same way about something—they all want to beat Harvard or Brown or whoever we’re playing.”

Football coach Buddy Teevens ’79 calls Sheehy “a wonderful addition” who has given him “total support,” but is also quick to say Sheehy hasn’t been the only savior, pointing to improvements that were already under way. “There is a lot of stuff that Jim Wright, Josie Harper and Bob Ceplikas had put into place that was starting to make an impact. It just wasn’t showing up yet in the bottom line in athletics,” Teevens says. “I think Jim Kim and Harry Sheehy have been able to take all that and add an energy level that has allowed us to spring forward.”

Sheehy’s hopes for the future include the building of an indoor practice facility to take some of the pressure off Leverone Field House, which can be bedlam in the winter as track, football, lacrosse, soccer, softball, golf and rugby vie for access. And fundraising looks to remain an important part of his job. But more than any one construction project or fundraising initiative, his real goal for Dartmouth athletics is less material: He wants the College to get its swagger back.

“There was probably a time when Dartmouth didn’t feel comfortable in its own skin, when it was trying to be something it wasn’t,” Sheehy says. “When you look back at when it was successful, it’s because it had a good handle on and was very self-possessed about what it was and what it wasn’t. I always say, ‘Dartmouth is not a good Harvard in the woods.’ The alums know that. And I think we’re getting back to the place where those of us working here know that, too.”

Brad Parks is a novelist whose next book, The Girl Next Door, will be published by St. Martin’s Press in March.