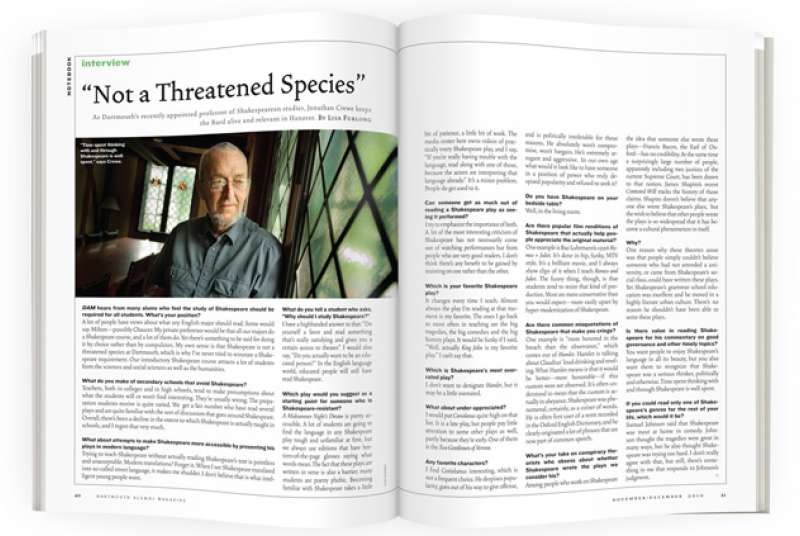

“Not a Threatened Species”

DAM hears from many alums who feel the study of Shakespeare should be required for all students. What’s your position?

A lot of people have views about what any English major should read. Some would say Milton—possibly Chaucer. My private preference would be that all our majors do a Shakespeare course, and a lot of them do. Yet there’s something to be said for doing it by choice rather than by compulsion. My own sense is that Shakespeare is not a threatened species at Dartmouth, which is why I’ve never tried to reinstate a Shakespeare requirement. Our introductory Shakespeare course attracts a lot of students from the sciences and social sciences as well as the humanities.

What do you make of secondary schools that avoid Shakespeare?

Teachers, both in colleges and in high schools, tend to make presumptions about what the students will or won’t find interesting. They’re usually wrong. The preparation students receive is quite varied. We get a fair number who have read several plays and are quite familiar with the sort of discussion that goes around Shakespeare. Overall, there’s been a decline in the extent to which Shakespeare is actually taught in schools, and I regret that very much.

What about attempts to make Shakespeare more accessible by presenting his plays in modern language?

Trying to teach Shakespeare without actually reading Shakespeare’s text is pointless and unacceptable. Modern translations? Forget it. When I see Shakespeare translated into so-called street language, it makes me shudder. I don’t believe that is what intelligent young people want.

What do you tell a student who asks, “Why should I study Shakespeare?”

I have a highhanded answer to that: “Do yourself a favor and read something that’s really satisfying and gives you a certain access to theater.” I would also say, “Do you actually want to be an educated person?” In the English language world, educated people will still have read Shakespeare.

Which play would you suggest as a starting point for someone who is Shakespeare-resistant?

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is pretty accessible. A lot of students are going to find the language in any Shakespeare play tough and unfamiliar at first, but we always use editions that have bottom-of-the-page glosses saying what words mean. The fact that these plays are written in verse is also a barrier; many students are poetry phobic. Becoming familiar with Shakespeare takes a little bit of patience, a little bit of work. The media center here owns videos of practically every Shakespeare play, and I say, “If you’re really having trouble with the language, read along with one of those, because the actors are interpreting that language already.” It’s a minor problem. People do get used to it.

Can someone get as much out of reading a Shakespeare play as seeing it performed?

I try to emphasize the importance of both. A lot of the most interesting criticism of Shakespeare has not necessarily come out of watching performances but from people who are very good readers. I don’t think there’s any benefit to be gained by insisting on one rather than the other.

Which is your favorite Shakespeare play?

It changes every time I teach. Almost always the play I’m reading at that moment is my favorite. The ones I go back to most often in teaching are the big tragedies, the big comedies and the big history plays. It would be funky if I said, “Well, actually King John is my favorite play.” I can’t say that.

Which is Shakespeare’s most overrated play?

I don’t want to denigrate Hamlet, but it may be a little overrated.

What about under-appreciated?

I would put Coriolanus quite high on that list. It is a late play, but people pay little attention to some other plays as well, partly because they’re early. One of them is the Two Gentlemen of Verona.

Any favorite characters?

I find Coriolanus interesting, which is not a frequent choice. He despises popularity, goes out of his way to give offense, and is politically intolerable for those reasons. He absolutely won’t compromise, won’t bargain. He’s extremely arrogant and aggressive. In our own age what would it look like to have someone in a position of power who truly despised popularity and refused to seek it?

Do you have Shakespeare on your bedside table?

Well, in the living room.

Are there popular film renditions of Shakespeare that actually help people appreciate the original material?

One example is Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 Romeo + Juliet. It’s done in hip, funky, MTV style. It’s a brilliant movie, and I always show clips of it when I teach Romeo and Juliet. The funny thing, though, is that students tend to resist that kind of production. Most are more conservative than you would expect—more easily upset by hyper-modernization of Shakespeare.

Are there common misquotations of Shakespeare that make you cringe?

One example is “more honored in the breach than the observance,” which comes out of Hamlet. Hamlet is talking about Claudius’ loud drinking and reveling. What Hamlet means is that it would be better—more honorable—if this custom were not observed. It’s often understood to mean that the custom is actually in abeyance. Shakespeare was phenomenal, certainly, as a coiner of words. He is often first user of a term recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary, and he clearly originated a lot of phrases that are now part of common speech.

What’s your take on conspiracy theorists who obsess about whether Shakespeare wrote the plays we consider his?

Among people who work on Shakespeare the idea that someone else wrote these plays—Francis Bacon, the Earl of Oxford—has no credibility. At the same time a surprisingly large number of people, apparently including two justices of the current Supreme Court, has been drawn to that notion. James Shapiro’s recent Contested Will tracks the history of those claims. Shapiro doesn’t believe that anyone else wrote Shakespeare’s plays, but the wish to believe that other people wrote the plays is so widespread that it has become a cultural phenomenon in itself.

Why?

One reason why these theories arose was that people simply couldn’t believe someone who had not attended a university, or came from Shakespeare’s social class, could have written these plays. Yet Shakespeare’s grammar school education was excellent and he moved in a highly literate urban culture. There’s no reason he shouldn’t have been able to write these plays.

Is there value in reading Shakespeare for his commentary on good governance and other timely topics?

You want people to enjoy Shakespeare’s language in all its beauty, but you also want them to recognize that Shakespeare was a serious thinker, politically and otherwise. Time spent thinking with and through Shakespeare is well spent.

If you could read only one of Shakespeare’s genres for the rest of your life, which would it be?

Samuel Johnson said that Shakespeare was most at home in comedy. Johnson thought the tragedies were great in many ways, but he also thought Shakespeare was trying too hard. I don’t really agree with that, but still, there’s something in me that responds to Johnson’s judgment.