Catch and Release

Wild trout are delicious. In a rustic camp, pan-fried is the way to go. Butter and pepper in a cast-iron skillet and a little lemon if you have it. The meat is delicate, flaky, and mild, and it melts in your mouth. With a little practice, you can deftly peel off the fine, colorful skin and remove the pinkish-gray flesh by flicking the fork parallel to the tiny bones. You get boneless morsels and leave nothing but a dainty skeleton.

Wild trout are delicious. In a rustic camp, pan-fried is the way to go. Butter and pepper in a cast-iron skillet and a little lemon if you have it. The meat is delicate, flaky, and mild, and it melts in your mouth. With a little practice, you can deftly peel off the fine, colorful skin and remove the pinkish-gray flesh by flicking the fork parallel to the tiny bones. You get boneless morsels and leave nothing but a dainty skeleton.

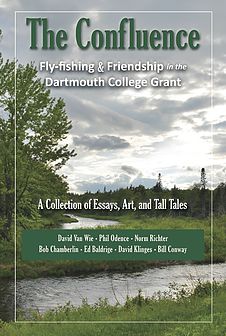

The Boys—Bob Chamberlin, Th’83, Norman Richter ’79, Edwin Baldridge ’79, William Conway Jr. ’79, David Klinges ’79 and the two of us—all love trout, but we almost never eat them in the Grant. Maybe once every few years. Seriously. Some may assume that our catch is for consumption, but that’s not how we roll.

Rather, we are proponents of the catch-and-release ethic, doing our best to return the fish unharmed to the river, to watch them dart off and hide in the waters from whence they came. We like to think of our excursions as “visiting the fish” and that we are simply seeking to have a brief interlude with them before we go back to our business and they to theirs. Sort of like visiting a piscine Oracle or the Dalai Lama with fins.

On the few occasions we have kept a fish it is usually because we have inadvertently injured it and realize that the poor creature has suffered too much trauma to return it to the water. The best way to honor the fellow’s memory, we’ve determined, is to sauté and share him as a special hors d’oeuvre.

Fortunately, injuries to fish are infrequent, and the odds of the fish being sizable enough to share are small, so when you multiply them together….Well, we don’t keep many, and it’s been a few years since we haven’t put one back.

The Boys aren’t left-wing radical fish huggers. It’s a question of circumstance. Many of us are happy to eat plentiful saltwater fish. When Guy lived in Wyoming years ago, he would catch a chunky rainbow trout for dinner about once a week from the Shoshone River down behind his office. And Phil likes to tell the tale of a fatal trout encounter he and Billy had years before that, which we’ll share in Phil’s own words:

In September of 1977, Billy and I set out from Philadelphia in my Toyota Corolla Liftback aimed for points west. We would drive 23,000 miles in eleven weeks. Our drive would take us from the depths of gambling tables in Las Vegas and dive bars in Pojoaque, New Mexico, to the summits of Nob Hill and various 14,000-foot peaks. We would encounter drug addicts, Mexican hustlers and imaginary Swiss women (long story), as well as nuclear scientists, future senators and Olympic silver medalists.

It’s an epic tale, and the full scope of those adventures is sufficient fodder for another written work, not this one.

In early October, a few weeks into our journey, we found ourselves with packs on our backs, slogging through deep snow atop Montana’s Sperry Glacier. Sperry extends into Gunsight Pass in the central northern part of Glacier National Park, just south of the Canadian border. On the western side of the pass was Snyder Lake, beside which we would lay our heads that night. Perhaps we were a little out of shape from two weeks of driving. At any rate, we were exhausted and starving when it came time to make camp after that first day of hiking. It was to be a several-day trip, and we had stocked up on your normal crappy camping food. But, while not hunter-gatherers, we were guys ready to chomp on some real live protein.

For years I carried, in one of the outer pockets of my old frame pack, a rudimentary fishing kit. It comprised a black and gray plastic 35-mm film canister (a container that someone rifling through my pack might have thought contained something else), a wine cork wrapped in monofilament, a small paper packet containing a half-dozen hooks and several split-shot lead sinkers.

Once our tent was pitched and our bags were pulled from their stuff sacks to fluff up, we decided, with no great hopes, to see if we could pull a fish from Snyder Lake. We fashioned a crude drop line rig on a fat stick using the cork bobber, a couple of sinkers and a hook. Having no luck finding a patch of soil rich enough to support worms, we were able to scrounge a hunk of medium sharp cheddar from our meager larder. From the shore, the weight of the sinkers allowed us to swing the end of the line back and forth enough to get a good toss, maybe fifteen or twenty feet out into the lake.

It seemed a long shot, but soon—it might even have been the first “cast”—we had a bite that turned into a beautiful ten-inch trout. In all we caught six or eight equally good-sized fish. And then we stopped, because we had enough. Billy cleaned the catch while I fired up the same one-burner compact Coleman stove I use to this day. We pan-fried the fish in some canola oil from a small squeeze bottle. The fry pan was half of a Boy Scout mess kit that I’d bought at an Army-Navy store (and which also continues to accompany me to the backwoods). I also travel with small vials of salt and pepper, enough to season a terrific meal. It’s called catch and chow down.

That hike and that meal are among my fondest backwoods memories. I am less fond of the memory of the eight-inch snowfall that night, our collapsed tent and our frigid retreat. That, too, is a story for another tome.

———

Catch and release is not a new concept, although relatively so given fishing’s ancient history. The caveman who first figured out how to get a fish out of a stream had only one thing in mind. In those days before taxidermists and digital cameras, the best recognition he might receive was a grunt from his wife at the size of his catch and the size of the meal. But today, in the developed world anyway, few people fish our lakes and streams to feed the family, even here in New England, although it does happen. Billy and Phil’s circumstance was a clear exception. For most fishermen, it’s really about the sport. Catch-and-release fishing is the logical extension.

The concept was pioneered in England in the nineteenth century. That little country was on the cutting edge of sport fishing and the modern-day problem of bumping into constraints in natural resources (which is why they went off and started an empire). With the human population outstripping the kingdom’s fish population, early conservationists realized that limiting the take was the only way to preserve fish stocks.

In those days, our land was still a great wilderness and virtually all resources were in great abundance. You could dump whatever you needed to dump from the sparsely populated shores of a river, and the water would purify itself before it reached the next dumper. Plus, there was no shortage of fish. Around about the early part of the twentieth century, however, the burgeoning population led to more people with leisure time and, so, more fishermen. Combined with the shrinking miles of healthy fish habitats, inevitably the curves crossed such that there were more fishermen than fish to support them, and U.S. conservationists began to advocate for catch and release here as well.

An early proponent was Lee Wulff, the fishing icon, who in 1938 wrote, “A good gamefish is too valuable to be caught only once.” How concisely the laconic Wulff captures our philosophy.

Bernard “Lefty” Kreh, the great southpaw caster and one of the best-known fishing guides, was also a big proponent, including saltwater fish. He advocated for catch and release among fellow guides in South Florida, where he resided in the 1960s. Through research, Lefty demonstrated that the fish his clients were catching had been getting smaller over time. Eventually he was able to convince many guides that, in the long run, catch and release would be better for business. Explaining this to people, Lefty was known to quip, “Do you cook up your golf balls after playing golf?” Kreh turned 90 this year and is still a vocal catch-and-release advocate.

Kreh and many others have written how-to guidelines. Fish are delicate and don’t do well out of water. Releasing one in an unhealthy state is hardly more effective than shoot and release, which, obviously, has never caught on with hunters. So, the guidelines are all about keeping fish healthy and uninjured. It starts with not playing the fish to the point of exhaustion. Actually it starts with selecting tippet that’s strong enough to allow you to haul a resisting the fish in without breaking. Ideally, the fish never comes out of the water and you are able to remove the hook quickly.

Fly-fishing inherently lends itself to catch and release as it utilizes a single hook. Generally, the fly hook pierces only the trout’s cartilaginous lip, so the hook comes right out with no harm done. But sometimes an enthusiastic trout will get hooked a little too well. Most of us use a hemostat or small pliers to rotate the hook point out. Barbless hooks are required in some waters, and bending down the barb makes for easier removal. We also use special nets that are fairly soft, fine meshed and forgiving, so that fish aren’t injured by the net.

When removing fish from the water or the net, we wet our hands to go easier on the mucus coating that protects the fish (trout are a little slimy). Finally, when the fish is tired, it’s good practice to hold it gently facing upstream to “catch its breath” until it squirms loose and scoots away.

———

Not all frequenters of the Grant subscribe to the catch-and-release philosophy, including a certain professor we run into from time to time. Phil likes to tell it this way:

At Hellgate now and then, I run into one of my favorite Dartmouth professors. At the end of his extremely popular freshman history seminar, he told me, “Well, you’re no genius, but I think you’ll get through Dartmouth.” How’s that for a vote of confidence?

The guy is a character—an alum, born and raised in a Maine mill town and you couldn’t miss it in his accent. It’s not way out on a limb to say the guy knows more about his field than anyone on the planet and is an extraordinary storyteller.

Thus, it was a delight to bump into my old prof that first time in the pools just above Hellgate Gorge. He was kind enough to feign remembering me. Evidently he and his wife (who always seemed to be back at the cabin cooking) had been regulars at the Grant for decades. They liked the fishing around Hellgate, but his practical streak kept him on the road side of the river in the Gorge Cabin, where our group has yet to stay. We talked about getting together for drinks, though that never happened. Still, it was always nice to see him on the river and chat him up briefly, which seemed to happen every couple of years.

Here’s the thing about the good professor: He’s a worm fisherman and has no use for the idea of catch and release. He uses a rig like you’ve never seen. A fly rod with some kind of attractor, a fly I think, below which hangs a 6- or 12-inch leader weighted down with some split shot (lead, of course) and a hook with a live worm. Typically, he uses the length of the rod to dip the bait into various likely holes at the head of pools, below little falls and along a foam line. Sometimes, though, I saw him bumble the worm along the bottom, using a technique not unlike nymphing.

And, he would slay them. And I do mean slay. On a day when The Boys were having moderate luck, I recall him pulling a string of trout out of a stream-side pool where he was keeping them cold. There must have been six or eight, all more than ten inches, very unusual that far upstream.

In all our years of going to the Grant, I’ll bet that, collectively, the seven of us Boys have kept fewer than a dozen fish. Total. We even feel funny having barbs on our fly hooks. How seemingly incongruous that a highly educated, supremely thoughtful nature lover such as the good professor would have such apparent disregard for the tragedy of the fishing commons, especially in this unstocked, wild trout water. Okay, we wouldn’t object to keeping a few, but it’s been years since “catching your limit” was an admirable goal.

I know I sound elitist when I say, “You can take the boy out of the North Woods, but…,” But I believe he is actually the elitist, of the Maine woods kind. He, at least implicitly, must feel that because he grew up fishing this way, it remains his right to continue to do so. It’s no business of the invading flatlanders, the cause of all that fishing pressure anyway (by Gawd), to tell him what should or shouldn’t be on the end of his line. He’s that kind of guy.

I wish he’d do differently, but I actually buy the squatter’s-rights argument. It’s a disposition I share, one that prompts me to disregard the decade-old one-way sign on Sea Street in Cotuit, the little village on Cape Cod where I spend much of my time. I grew up traveling from Main Street to Oceanview by way of Sea Street, and I will continue to travel that way (Gawdammit) even though a one-way sign now points in the other direction. At least my old professor isn’t breaking the law.

———

But The Boys are all about catch and release and have a great rule to facilitate the practice: If we bring a fish within a rod’s length and it spits the hook, we can consider it caught and released. We call it a long distance release, or LDR.

One of us: “How did you do, Bob?”

Bob: “Well, I hooked and lost a nice one, landed two about ten inches, and had a couple LDRs, both thirteen or fourteen inches.”

Statistically speaking, fish that are long distance released are about 2.5 inches longer than those we get to see up close. Go figure.

We also have a term for when the fish hits your fly but you miss the hook-up altogether. We call it low-impact fishing. When the fish are falling short of even hitting your fly, we call that “unproductive waters.” There are days when we go really easy on the trout population, especially Klingon.

To discourage their keeping smaller fish, we tell our occasional male guests another of our rules: “You can only keep fish that are bigger than your pecker.” It is entertaining to see the look on their faces while they try to decide whether this is a good thing or a bad thing.

Today, organizations ranging from the National Park Service to Trout Unlimited strongly encourage catch and release. A Park Service brochure says:

“Catch and release fishing improves native fish populations by allowing more fish to remain and reproduce in the ecosystem. This practice provides an opportunity for increasing numbers of anglers to enjoy fishing and to successfully catch fish. Releasing all native fish caught while in a national park ensures that enjoyment of this recreational opportunity will last for generations to come.”

The Boys agree, but we recognize that there are different strategies for managing fishing waters that may be under more or less fishing pressure from the masses. Waters closer to population centers are heavily stocked with hatchery trout in what are called “put and take” fisheries—the idea being that many people do, in fact, want to catch their limit for the table or freezer. Essentially, instead of delivering to the store, a state hatchery delivers them to the local stream. In rural New England, where incomes are low and jobs are scarce, the local population may rely on fish, venison and wild turkey to help feed the family. It’s a good way to accommodate the consumptive fishing pressure, thereby relieving the pressure in wilder places, such as the Grant.

Some lakes and rivers, believe it or not, may be over-stocked with certain species or size classes of game fish. Fishery managers may encourage anglers to take and keep some species to benefit others (e.g. taking lake trout from Maine’s Sebago Lake to help the salmon population) or may have a “slot limit” that allows anglers to keep only a certain size (say, six to nine inches) while releasing the rest to allow the larger fish to grow even bigger.

In most of the Grant, catch and release is voluntary, as a brochure published in 2012 by the College explains:

The following provisions are voluntary at this time. Persons fishing in the Grant are strongly encouraged to:

A. Practice “catch and release” of all trout and salmon.

B. If you keep fish, follow a voluntary two fish per person per day limit.

C. Use single barbless hooks on all flies, lures or bait hooks.

Only the waters in the southern part of the Grant are regulated as catch and release, artificial lures only:

From the confluence of the Dead Diamond and Magalloway River near the southerly end of the airstrip, upstream to the confluence of the Swift Diamond and Dead Diamond rivers near Peaks Cabin, and on that portion of the Magalloway located in New Hampshire upstream of its confluence with the Dead Diamond, only single barbless-hook lures or flies may be used. No worms or bait are allowed. All trout must be released unharmed.

In Lamb Valley Brook, Loomis Valley Brook and Alder Brook, wild trout regulations apply. Only single barbless-hook lures or flies may be used. No worms or bait are allowed. All trout must be released unharmed. These waters are open to fishing January 1 to Labor Day only.

It’s always bugged and bewildered us that the proverbial “they” don’t just make all the waters of the Grant compulsory catch and release or, better, fly-fishing only. Why not? Perhaps revealing our elitist prejudice, we have been inclined to speculate that this is a consequence of the Great Unwashed, less forward thinking than we are, pressing the College to maintain the status quo.

Not so, it turns out. According to the master plan for the Grant, the College feels that more restrictions could actually be worse for the fish population. The argument is that the rivers and fish are technically public resources, so stricter regulations would require public hearings that would draw unwanted attention to the wild fishery. Furthermore, officially designated catch-and-release waters must be marked as such on maps of the area and therefore might act as a bulls-eye for clever fishermen. The College calculates that the lesser evil is to keep the waters on a daily limit while educating visitors and encouraging conservation practices. This also allows visitors who want to enjoy a trout dinner, after traveling all this way, to do so at their discretion. As we’ve told our kids, everything is okay in moderation.

There is one, very exclusive group of fish that must be released everywhere in the Grant. Fish tagged and equipped with antennae must be returned to the water and fishermen are asked to report the catch to New Hampshire Fish and Game. Although we have never caught one of these high-tech trout, we have had some interesting encounters with wildlife biologists conducting fascinating studies. One woman we spoke with, who was operating a radio receiver above the Gorge, excited us with the discovery that there was a twenty-inch trout downstream, within a hundred feet. None of us has ever caught a twenty-inch trout in the Grant. The radio researchers have discovered that the trout of the Grant are much rangier than they had believed. Some tagged fish regularly head to the Magalloway, Rapid and Androscoggin rivers in the low-water warmer months and come back in the fall.

Whatever the regulations, The Boys will continue to release as many fish as we can. The more we release, the happier we are. And why eat fresh sautéed trout when there’s Veg-All?

We like to think that on occasion we encounter fish we’ve met in the past and released as manifestations of Lee Wulff’s chestnut about the value of a game fish. Guy puts it another way: “I like watching them swim away as much I like catching them.”

We all do.

“Catch and Release” from The Confluence: Fly-fishing and Friendship in the Dartmouth College Grant (Peter E. Randall Publisher, 2016) is reprinted here with permission from the publisher. Image by Bob Chamberlin, Th’83.