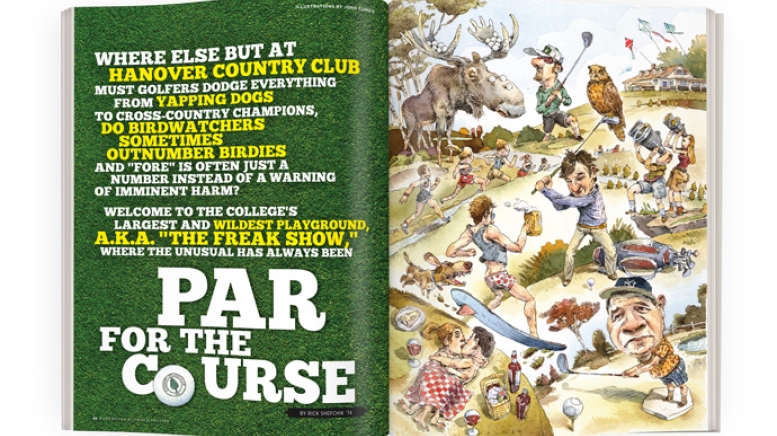

There is a 123-acre parcel of green space on the north edge of campus where students picnic, fly kites and sleep overnight in tents. It has been the scene of ski jumping, snowboarding and legendary—perhaps apocryphal—daredevil stunts. Cars sometimes find their way there, as do couples pushing baby strollers. It’s a place where moose wander and where the date of a future U.S. presidential candidate went surfing. There are even bodies buried there.

The land in question is the venerable, quirky, beloved Hanover Country Club (HCC). Since shortly after its establishment at the north end of Rope Ferry Road in 1899, HCC has provided the College with an idyllic wooded setting for golf.

But it has been so much more than just a golf course.

“Our group of guys affectionately refers to HCC as ‘the freak show,’ ” says Scott Peters, a former club champion who grew up playing HCC with his brother Mike, while his father, Seaver Peters ’54, was Dartmouth’s athletic director. “There are walkers, joggers, the cross-country team, sledding in winter—there’s always something walking or running past you on the golf course. I’ve been there so long I don’t even notice it anymore. That’s part of the charm of a college course.”

Izzy Johnson, who pulled regular shifts when her late husband, Bill, ran the course and coached Dartmouth’s men’s golf team from 1967 to 2001, has her own memories.

“One time when Bill wasn’t there somebody came running into the clubhouse and said, ‘We’ve got a problem here,’ ” says Johnson. “I looked up and saw a young couple with children who’d put out a picnic basket in the middle of the third fairway. I looked over another hill and somebody was flying a kite, and there were people walking dogs down the first fairway. I didn’t know where to start, except to tell the golfers to hold back until we got things cleared out. It was just that kind of place—never a dull moment and always a lot of fun.”

“It’s kind of a zoo,” says Steve Lyon, the club’s superintendent from 1981 to 2009. “A lot of dog walkers get irate every spring when the course opens.” Lyon also recalls that birdwatchers from as far away as Pennsylvania used to walk out onto the course with oversized binoculars to catch glimpses of a pair of nesting merlins. Deer are plentiful, and golfers sometimes discover fawns lying in the tall grass. Every two or three years a moose is spotted in the early morning fog. At one point woodchucks seemed to be running all over the place, until Lyon discovered that the animal control officer in Norwich, Vermont, was trapping the critters and releasing them near the ski jump. “That’s been taken care of by neighbors walking their dogs,” Lyon says.

Predictably, the course attracts more visitors in warmer months, but it is hardly dormant in winter. Sledders and skiers alike patrol the grounds, and Howl at the Moon, an annual local restaurant sampling event, takes place on a February evening timed to coincide with the full moon. Organizer Mike Silverman, manager of the DOC’s cross-country ski center, says he’s had anywhere from 400 to 700 people moving on foot or snowshoe along paths lit by tiki torches among seven food stations. “We don’t recommend that people do it on skis,” Silverman says. “The lines become awkward.”

Until 1993 the College’s ski jump, located on the hillside behind the 13th green, was the draw—and not just for skiers. Animal House coauthor Chris Miller ’63 mentioned it in his 2006 memoir: “There was a story that in the early ’50s an [Alpha Delta Phi brother] went off the ski jump when there was no snow. In a baby carriage. And lived.”

“I’ve heard that story and believe it to be true,” says Scott Peters. “It’s part of the folklore of HCC. The ski jump was a huge part of the course, socially. Students would climb up and have a few beers.”

Students have long enjoyed other course activities that give “twosome” a new meaning. Miller wrote about them in his memoir: “Of all Dartmouth big weekends, Green Key was the sweetest. You could go picnicking, hiking or swimming.…Best of all, it was warm enough to get laid on the golf course.”

Even Hillary Clinton has a ski jump story: In 1967 the future first lady, U.S. senator and secretary of state (Wellesley class of ’69) visited the golf course with her Winter Carnival date, a homesick Californian.

“I don’t know what he thought was going to happen, climate-wise, when he went to Dartmouth,” Clinton told tablemates in a dinner-party conversation that was videotaped and is posted on YouTube. “He was so miserable. All he did was talk about surfing.…We went to some parties, the bonfire, all of that. Then he went and said, ‘No evening of fun is complete without me surfing.’ He puts on his swimming trunks, he gets his surfboard and he heads down to the golf course…drunk out of his mind, and he’s trying to surf down this little, tiny hill. We were all watching this in amazement. We thought he’d freeze to death. He was in these little, tiny swimming trunks. And finally, you know, he dropped out of Dartmouth and went back to California.”

Other students continued to enjoy the course’s unusual feature. “We used to talk every once in a while about going up the ski jump, and one time after an all-nighter we went out there about 6 in the morning, ready to give it a go,” recalls John Penberthy ’74. “When we got there we all took one look at how high the damn thing was and decided it was time to go to bed.”

Not everyone has been restrained by such last-minute attacks of common sense, however. Snowboarders love the new 14th hole. After heavy snows, Lyon says, they’ll build a jump from which they can get 30 to 40 feet of air.

Students have long enjoyed other course activities that give “twosome” a new meaning. Miller wrote about them in his memoir: “Of all Dartmouth big weekends, Green Key was the sweetest. You could go picnicking, hiking or swimming.…Best of all, it was warm enough to get laid on the golf course.” Lyon says that in those days, before women were admitted to Dartmouth, the course was a tent village on Green Key weekend, when students would camp out with their imported dates.

He says he used to find couples at the jump when he made his early-morning sweeps of the golf course. Come spring he’d find them on greens and fairways. “I made the first tour every day at sunrise,” Lyon says. “Twenty or 30 times I had to wake couples up on the third or fourth green. Once somebody drove a Triumph out there and I found a couple asleep in it. Those were the days before automatic irrigation. Now [the sprinklers] come on at 4 a.m., so they’re forced to move.”

The club shares fringes of its land with Pine Park, a 90-acre tract of land jointly overseen by the Town of Hanover and the College. The park includes maintained jogging trails around and through the course, leading to numerous close calls between oblivious joggers and flying Titleists. “It’s a multi-use facility, and sometimes it creates a little confusion for golfers,” says HCC head pro Alex Kirk. “That’s a fine line we walk, where the golf course ends and where the park begins.”

“It is an issue,” says Brian Kunz, president of the Pine Park board of trustees. “Runners and people who are not golfers don’t appreciate what a golf ball can do if you run into it. We use signage to tell people that they need to take care and take responsibility, but not to fear going into Pine Park. We hope golfers will pause to let walkers go by.”

Despite the distractions, serious golfers find a lot to like about HCC. When it underwent a $3-million renovation in 2000, golf course architect Ron Prichard was asked to stretch it out from a sporty 5,876 yards to a demanding 6,472. While planning the new par-3 12th hole at the highest point on the property, Prichard was surprised to learn that the woods to the right of the tee were used as a burial ground for medical school cadavers—a practice that ended in the 1960s. Prichard’s first plan was to situate the tee so that shots would have to carry the cemetery, but zoning rules didn’t allow for it.

The new holes—6, 11, 12, 16 and 17—were configured in such a way that the clubhouse (currently a barn that dates to 1820) could eventually be relocated to Lyme Road, allowing for two nines that both returned to the clubhouse. That remains a dream: There are no plans—or funds—to build it. “It’s hard to walk back in after nine holes,” says Kirk. “But there is a nice view from the current clubhouse.”

That view is something Izzy Johnson still treasures. “The clubhouse is very welcoming, the least stuffy clubhouse you’d ever find anywhere,” she says. “The porch looking out over the course has one of the prettiest views in all of Hanover. It’s so peaceful. You can look out over the course before you play, then come and sit on the porch, have a few beers and talk about how the golf course got you.”

Some members say the HCC course was more fun to play before it was lengthened and toughened. The 17th hole—which can be played as a tight 280-yard par 4 or as a long, target-style 517-yard par 5—has proven controversial, but many of the changes were obvious improvements. The green on the uphill par-3 14th is now more visible from the tee. Previously, golfers on the tee below had to wait for the group ahead to ring a bell when they were leaving the hidden green.

“It used to be a fun thing when kids—who shall go unnamed—would run down, throw the ball in the hole and disappear into the woods to make people think they got a hole in one,” says Scott Peters.

When Andrew Sigler ’53, Tu’56, opened the private, upscale Montcalm Golf Club in Enfield, New Hampshire, in 2004, a number of HCC players made the move to the new club, perhaps tired of putting up with all the quirks at Hanover. Most have found their way back. “That’s where our friends are,” says Roger McWilliams, a former HCC club president. “It is probably one of the best melting pots in the Upper Valley. You see everybody—physicians at the hospital, incredibly bright professors, high-tech people who work at Centerra and regular guys who run all the businesses.”

There seems no pressing need to make the golf course self-sustaining. “As with all of our athletics facilities that bring in revenue, the golf course operates at a deficit,” says Rick Bender, director of varsity athletic communications. “The money that is brought in helps offset the costs and reduces the impact on the budget.”

Club members have long been concerned, however, that the College administration doesn’t love the course as much as they do. Jim Kim was the first president in decades to play golf—and he was somewhat of a fanatic, frequently teeing off at dawn. President Philip Hanlon ’77 has a personal connection to the game, too. He not only played on his high school golf team in Gouverneur, New York, but he also met his wife, Gail Gentes, during a round. He speaks highly of the course. “The HCC is a treasure, even for those of us who don’t get to play as much as we’d like,” says Hanlon. “It’s about community and fellowship. It was that way when I was a student and it’s the same today. You don’t have to nail a 250-yard drive down the middle to feel like your day was a success. You might watch a doe and her fawns amble through your shot or share a laugh with colleagues and friends back at the clubhouse. That’s a good day in my book.”

Lyon hopes that Hanlon’s interest in golf will benefit a course that hasn’t always been high on the College’s priority list. “If you have a president who enjoys playing golf, you may get the nod to do a few more things,” Lyon says. “They’ll never let it run down, but they could make a decision to abandon it. There’s been talk about building it somewhere else—Etna or up near the hospital—but building something else here would require rezoning and that would be up to the town.”

Would Dartmouth someday plow up its backyard golf course to make way for more buildings? The current value of HCC—land and clubhouse—is $6,463,100, according to Hanover’s tax assessor, but realtor Ned Redpath of Coldwell Banker Redpath & Co. of Hanover says it’s hard to put a value on land that close to a growing college, particularly in the wake of a real estate slump. “For a number of years the talk has been HCC is far and away the best option for expansion of the campus,” Redpath says. “That’s the only direction they can go—north—but I really don’t think they need to do too much more out in that direction. And if they do, they’d have to spend $10 million on a new golf course. What’s accomplished?”

Redpath suggests the College could buy Montcalm (“Andy [Sigler] is a little older, and I don’t know if it has the same buzz for him that it used to”), but that’s an inconvenient 12-mile drive from campus. Moving off-campus would be a detriment not only to golfers but also to the Dartmouth men’s and women’s cross-country teams. Both teams practice at HCC and both went to the NCAA championships last fall. Men’s coach Barry Harwick ’77 calls the course a great place to run because of its ideal turf and varied elevation, where his team can climb the steep hills or do speed work along the flats near Lyme Road. Former women’s coach Mark Coogan says Dartmouth has better practice grounds than any of its competitors. The proof would be Abbey D’Agostino ’14, the 2013 NCAA national cross-country champion. She’s even won over the golfers, Coogan says: “She’s considered the best athlete on campus. They’ll ask, ‘Which one’s the superstar?’ ”

There appears to be no immediate threat that the College would use the HCC site for any other purposes. Tim McNamara, associate director of real estate for the College, cites the significant investment made in the course’s 2001 renovation, as well as ongoing improvements. The 18-hole course and the practice holes on the east side of Lyme Road are zoned as part of Dartmouth’s institutional district. Very few College activities can take place outside that district, McNamara says.

“Before the College did anything on the golf course itself, which would require relocating it, my guess is they’d dig up the practice holes for institutional use,” McNamara says.

Even those who never played golf at HCC and have no emotional attachment to the course see it in a different light when they return, says Kirk. “I see a lot of alumni who came back in their 60s and 70s who thought Hanover Country Club was where they went sledding or maybe they had some fraternity activity out there,” he says. “It was a park to them. They were not thinking golf. But as they move on in life, as they retire, they see prestigious golf courses around the world and they almost wish they’d got to play here earlier.”

Rick Shefchik is a newspaperman-turned-novelist—and avid golfer—who lives in Stillwater, Minnesota. His books include Amen Corner, Green Monster and Frozen Tundra.

Shotmakers

Hanover Country Club has hosted an impressive list of notables in its 115-year history.

President Woodrow Wilson, referred to in the August 1913 issue of American Golfer as the “first player in the land,” made several trips to Hanover during his presidency. Wilson and his playing partner were unable to find caddies, so Wilson’s chauffeur and his Secret Service bodyguard carried the bags. Wilson, a Princeton grad, found HCC “a test for his skill and possibly knows now why the Dartmouth College team occasionally proves such a tough customer for the Princeton representatives in intercollegiate play,” the magazine reported. Undaunted, Wilson returned to play in 1914 and 1915.

President Woodrow Wilson, referred to in the August 1913 issue of American Golfer as the “first player in the land,” made several trips to Hanover during his presidency. Wilson and his playing partner were unable to find caddies, so Wilson’s chauffeur and his Secret Service bodyguard carried the bags. Wilson, a Princeton grad, found HCC “a test for his skill and possibly knows now why the Dartmouth College team occasionally proves such a tough customer for the Princeton representatives in intercollegiate play,” the magazine reported. Undaunted, Wilson returned to play in 1914 and 1915.

Glenna Collett, a six-time U.S. women’s amateur champion, came to Hanover at the peak of her career in October 1925 to visit her brother Edwin, class of 1929. With partners, she and the club’s first professional, Tommy Keane, squared off in a best-ball match. Collett shot a 79 and won the match with a tough par putt on the 18th green.

Glenna Collett, a six-time U.S. women’s amateur champion, came to Hanover at the peak of her career in October 1925 to visit her brother Edwin, class of 1929. With partners, she and the club’s first professional, Tommy Keane, squared off in a best-ball match. Collett shot a 79 and won the match with a tough par putt on the 18th green.

Francis Ouimet, who popularized golf in America when he defeated British stars Harry Vardon and Ted Ray in the 1913 U.S. Open, attracted a large gallery when he played HCC on October 10, 1931, less than a month after winning his second U.S. amateur title. He shot a 76, disappointing the crowd, according to The Dartmouth.

Francis Ouimet, who popularized golf in America when he defeated British stars Harry Vardon and Ted Ray in the 1913 U.S. Open, attracted a large gallery when he played HCC on October 10, 1931, less than a month after winning his second U.S. amateur title. He shot a 76, disappointing the crowd, according to The Dartmouth.

Gene Sarazen, the first professional golfer to win all four major golf championships, entertained a crowd of 400 with a shotmaking demonstration at HCC in 1936, the year after he won the Masters. Sarazen returned in 1971 to play a round with Bill Johnson.

Babe Ruth, the Yankees slugger, was once a guest at the Hanover Inn, and club lore indicates he played a round at HCC in 1941. In retirement Ruth said, “I played 365 rounds of golf last year. Thank God for whoever invented golf. I’d be dead without it.”

President Dwight Eisenhower did not have time for a full round the morning of his 1953 Commencement speech, but he played the first five holes, with a different caddie on each hole—each of whom received a silver dollar. In his speech later that day he mentioned the satisfaction of playing golf by the rules.

President Dwight Eisenhower did not have time for a full round the morning of his 1953 Commencement speech, but he played the first five holes, with a different caddie on each hole—each of whom received a silver dollar. In his speech later that day he mentioned the satisfaction of playing golf by the rules.

Jackie Robinson, who had retired from the Brooklyn Dodgers after the 1956 season, visited HCC in 1959, when he played a round with Tommy Keane and his son Tommy III.

Jack Nicklaus and his son Jackie, a prospective student, spent an October 1979 weekend touring campus, attending the Holy Cross football game and playing HCC. Nicklaus and head pro Bill Johnson played a 10-hole match for a beer, won by Johnson with an eagle putt on the 18th hole. “It was the best-tasting beer I have ever had,” Johnson said. Jackie eventually chose to attend the University of North Carolina. In 1989 his father’s design company redesigned the 7th and 10th holes.

—R.S.

A Course History

Formed in 1896 by 14 professors, students and townspeople—including President William Jewett Tucker, class of 1861—Hanover Country Club established its permanent home in 1899 with a nine-hole course.

The College, which had been fielding golf teams since 1904, bought the club and grounds for $12,000 in 1914. The land on which the first hole had been located was sold for home sites along Rope Ferry Road, and additional land was acquired from the Pine Park Association. The course was extended northward to the Vale of Tempe, now referred to as “The Gully.” A relocated barn became the clubhouse.

In 1922 the College hired Orrin Smith to expand the course to 18 holes, and Tommy Keane became the club’s first head professional. A decade later, Ralph Barton, class of 1904, who had worked on the grounds crew and taught math at Dartmouth, returned to Hanover to design an additional nine holes, donating his work to the College. It would remain in play until 1970, when Lyme Road was upgraded and pressure for more housing began to consume some of the holes. The most recent tweaks occurred in 2001 when Ron Prichard added almost 600 yards to the layout.

At one time HCC was administered by the College’s business office, but former athletic director Seaver Peters successfully advocated to have the course run by the athletic department. In 1967 Bill Johnson replaced Keane as head pro and Dartmouth golf coach. In his 36 years as coach Johnson brought Dartmouth golf to prominence, winning two Ivy League team championships, the 1970 Eastern Championship and coaching four All-Americans. His wife. Izzy, a fine golfer in her own right, put together Dartmouth’s first women’s golf team in 1981. Two years later her team won the ECAC championship behind All-American Sue Johnson Bower ’85, who grew up in Hanover.

Other notable HCC golfers include Austin Eaton III (son of Austin Eaton ’62), who won the U.S. Mid-Amateur in 2004, Jeff Julian and current men’s golf coach Rich Parker, both of whom played on the PGA tour. More recently Hanover native Peter Williamson ’12 won the North-South Amateur and was the eighth-ranked amateur in the world before turning pro.

—R.S.