Despite its fame and popularity as a tourist attraction, the Great Wall of China remains a mystery. For centuries much of its history has been buried in books or hidden in remote areas of the wall itself.

If there’s one person who might change that, it’s likely to be David Spindler.

Spindler has been studying the Great Wall for more than a decade and is now one of the world’s preeminent scholars on the subject. “He knows more things about the wall than anybody else working in the English language,” says Pamela Crossley, a Dartmouth history professor who specializes in Chinese history. “Even in Chinese, there are only a couple of lifelong scholars who might know as much about the wall.”

Although Spindler has a master’s on top of his A.B. in Asian studies—and a law degree from Harvard—he does not have a Ph.D. and has never had an academic post. His expertise has been acquired from independent research funded by speaking engagements.

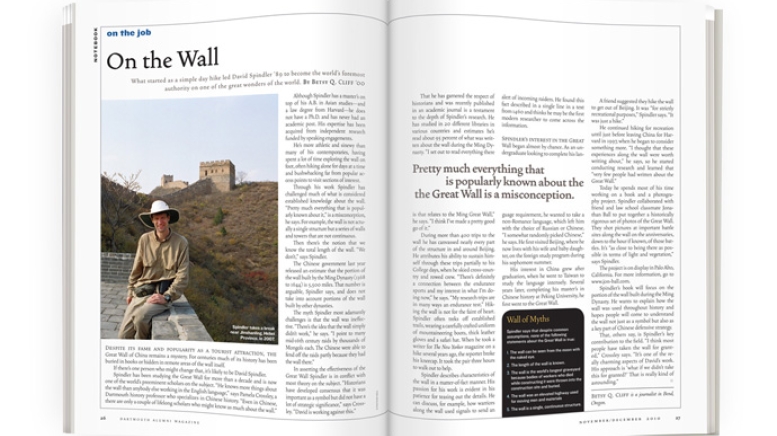

He’s more athletic and sinewy than many of his contemporaries, having spent a lot of time exploring the wall on foot, often hiking alone for days at a time and bushwhacking far from popular access points to visit sections of interest.

Through his work Spindler has challenged much of what is considered established knowledge about the wall. “Pretty much everything that is popularly known about it,” is a misconception, he says. For example, the wall is not actually a single structure but a series of walls and towers that are not continuous.

Then there’s the notion that we know the total length of the wall. “We don’t,” says Spindler.

The Chinese government last year released an estimate that the portion of the wall built by the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644) is 5,500 miles. That number is arguable, Spindler says, and does not take into account portions of the wall built by other dynasties.

The myth Spindler most adamantly challenges is that the wall was ineffective. “There’s the idea that the wall simply didn’t work,” he says. “I point to many mid-16th century raids by thousands of Mongols each. The Chinese were able to fend off the raids partly because they had the wall there.”

In asserting the effectiveness of the Great Wall Spindler is in conflict with most theory on the subject. “Historians have developed consensus that it was important as a symbol but did not have a lot of strategic significance,” says Crossley. “David is working against this.”

That he has garnered the respect of historians and was recently published in an academic journal is a testament to the depth of Spindler’s research. He has studied in 20 different libraries in various countries and estimates he’s read about 95 percent of what was written about the wall during the Ming Dynasty. “I set out to read everything there is that relates to the Ming Great Wall,” he says. “I think I’ve made a pretty good go of it.”

During more than 400 trips to the wall he has canvassed nearly every part of the structure in and around Beijing. He attributes his ability to sustain himself through these trips partially to his College days, when he skied cross-country and rowed crew. “There’s definitely a connection between the endurance sports and my interest in what I’m doing now,” he says. “My research trips are in many ways an endurance test.” Hiking the wall is not for the faint of heart. Spindler often treks off established trails, wearing a carefully crafted uniform of mountaineering boots, thick leather gloves and a safari hat. When he took a writer for The New Yorker magazine on a hike several years ago, the reporter broke his kneecap. It took the pair three hours to walk out to help.

Spindler describes characteristics of the wall in a matter-of-fact manner. His passion for his work is evident in his patience for teasing out the details. He can discuss, for example, how warriors along the wall used signals to send an alert of incoming raiders. He found this fact described in a single line in a text from 1460 and thinks he may be the first modern researcher to come across the information.

Spindler’s interest in the Great Wall began almost by chance. As an undergraduate looking to complete his language requirement, he wanted to take a non-Romance language, which left him with the choice of Russian or Chinese. “I somewhat randomly picked Chinese,” he says. He first visited Beijing, where he now lives with his wife and baby daughter, on the foreign study program during his sophomore summer.

His interest in China grew after graduation, when he went to Taiwan to study the language intensely. Several years later, completing his master’s in Chinese history at Peking University, he first went to the Great Wall.

A friend suggested they hike the wall to get out of Beijing. It was “for strictly recreational purposes,” Spindler says. “It was just a hike.”

He continued hiking for recreation until just before leaving China for Harvard in 1997, when he began to consider something more. “I thought that these experiences along the wall were worth writing about,” he says, so he started conducting research and learned that “very few people had written about the Great Wall.”

Today he spends most of his time working on a book and a photography project. Spindler collaborated with friend and law school classmate Jonathan Ball to put together a historically rigorous set of photos of the Great Wall. They shot pictures at important battle sites along the wall on the anniversaries, down to the hour if known, of those battles. It’s “as close to being there as possible in terms of light and vegetation,” says Spindler.

The project is on display in Palo Alto, California. For more information, go to www.jon-ball.com.

Spindler’s book will focus on the portion of the wall built during the Ming Dynasty. He wants to explain how the wall was used throughout history and hopes people will come to understand the wall not just as a symbol but also as a key part of Chinese defensive strategy.

That, others say, is Spindler’s key contribution to the field. “I think most people have taken the wall for granted,” Crossley says. “It’s one of the really charming aspects of David’s work. His approach is ‘what if we didn’t take this for granted?’ That is really kind of

astounding.”

Wall of Myths

Spindler says that despite common assumptions, none of the following statements about the Great Wall is true:

1. The wall can be seen from the moon with the naked eye.

2. The length of the wall is known.

3. The wall is the world’s longest graveyard because bodies of workers who died while constructing it were thrown into the construction site and buried.

4. The wall was an elevated highway used for moving men and materials

5. The wall is a single, continuous structure.

Betsy Q. Cliff is a journalist in Bend, Oregon.