In his seminal work on corporate strategy, United States of Advertisement: How Cars, Computers, and Cola Shaped a Nation, Jeremy Turnbull posits that PanCola’s “secret ingredient” ad campaign was the first modern use of marketing in America. “Not only did Houghton Forster provide a compelling—one might even say ‘viral’—narrative by which to interest customers in his product,” Turnbull writes, “but he also created, during that process, the concept of CEO-as-a-household-name, predating Lee Iacocca by over half a century.” Public engagement with Forster’s life story began on November 12, 1927, when Forbes published an interview with the inventor of Panola Cola. In the interview, he spoke of what he would leave behind, noting that his product belonged to the customers but that its creation, a singular moment alchemized into a singular taste, would forever and always belong to his family.

In his seminal work on corporate strategy, United States of Advertisement: How Cars, Computers, and Cola Shaped a Nation, Jeremy Turnbull posits that PanCola’s “secret ingredient” ad campaign was the first modern use of marketing in America. “Not only did Houghton Forster provide a compelling—one might even say ‘viral’—narrative by which to interest customers in his product,” Turnbull writes, “but he also created, during that process, the concept of CEO-as-a-household-name, predating Lee Iacocca by over half a century.” Public engagement with Forster’s life story began on November 12, 1927, when Forbes published an interview with the inventor of Panola Cola. In the interview, he spoke of what he would leave behind, noting that his product belonged to the customers but that its creation, a singular moment alchemized into a singular taste, would forever and always belong to his family.

“I’m just a soda jerk at heart,” Forster told Forbes. “I got to do by me and mine.”

His claim later in the interview to have discovered the secret ingredient during childhood did little to narrow the range of clues by which to identify it. As a child the world for Houghton Forster was one of myriad flavors. He would cringe at the pungency of tobacco cud hocked by farmers onto the board sidewalk. He would grin at the piquancy of his own sweat dribbled from the dirty brim of his woven flop hat. Over corn bread he liked to pour redeye. Into gumbo he liked to crumble saltines. With a biscuit he liked to sop molasses. He cooled off with Neapolitan ice cream during the summer. He warmed up with Old English wassail during the winter. Beneath a walnut tree he savored his first kiss from Annabelle, those crinkles in her lips, that down on her ears, tinged with the scent of honeysuckle, mellow and cool and buoyant, latticing the damp soil beneath them. He sneezed from dandelion at age ten. He chewed on birch bark at age four. He inhaled of rosemary at age nine. He teethed with sarsaparilla at age one. Near his mother’s dressing screen he could almost taste the eau de toilette, “A Smell Fresh from the Rhine,” that she bought by the quart from a perfumer based in Knoxville, and near his father’s medicine chest he would often smell the chicle lozenges, “Taste the Orient in Every Chew,” that he ordered from a circular sent by the T. Eaton Co. Limited. He preferred banana cake to monkey bread for breakfast. He preferred hush puppies to fried catfish for dinner. With confusion he sampled a piece of saltwater taffy. On a dare he took a whiff of a lady’s discarded underthings. After misspeaking he had to gnaw on a hunk of soap.

“What makes Panola Cola the sweetest thing around?” asked one of the first print ads for the secret-ingredient campaign. Under the sketch of a man glugging at a bottle of soda appeared the answer, “Our lips are sealed. Yours aren’t.”

Less than a year after the debut of such advertisements the initial wave of cola hunters arrived in Mississippi. Who they were varied as much as where they looked. At the schoolhouse where Houghton had been taught, a retired beekeeper made a rubbing of algebraic formulas etched into a desktop, clapped yellow dust from chalk erasers, and sifted through a pile of pencil shavings with a yardstick. A mother of five staked out the police station. A father of two cordoned off the fire department. Over an extended period of months, a team of experts, including a horticulturist, biologist, geologist, landscaper, chemist, and even an archaeologist, studied the lot where, decades earlier, Fiona Forster had tended a garden, its tilled rows of squash, collards, tomatoes, okra, and snap peas surrounded by various flowers: four-o’-clocks and verbena, old maids and phlox. The cartoonist for a syndicated gazette drew sketches of every show window in the business district. A subscriber to Popular Mechanics posed as an electrician in order to ransack the Avalon Cinema one town over. The coach of a champion basketball team kept a playbook of all train routes into the nearest depot. No matter who comprised the cola hunters or where they chose to search for clues, a raconteur panning a cakewalk, an asthmatic panning an orchard, a hypocrite panning a bait shop, what drove them to Panola County was the very same emotion felt by Houghton Forster on the day when, after finally discovering the sweet or savory or bitter or salty or sour taste of his secret ingredient, he combined a prototype of the syrup with carbonated water.

“Not a doubt in my mind,” he once said. “It was love at first sip.”

Although the concept of a secret recipe, ingredient, or formula would later be used to market everything from baked beans to fried chicken, few people realized how revolutionary it was at the time. What made the particular campaign so unique, J. Mumford Simms of Simms & Powell claims in Mum Is Not the Word: An Ad Man Tells All, wasn’t its sense of intrigue but rather of intimacy. “Prior to my agency’s work with PanCola, nothing was personal to the consumer,” writes the ad man, “but after my agency’s work with them, PanCola was like a part of your family.” J. Mumford Simms never shied from giving credit to Houghton. He would often admit it was Forster who thought up the campaign. He would often admit it was Forster who sold the idea to his country. On May 7, 1956, the Wall Street Journal corroborated those sentiments by concluding its obituary of Houghton Forster with the statement, grandiose but prophetic, that PanCola’s secret ingredient was “the rosebud to his entire family saga.”

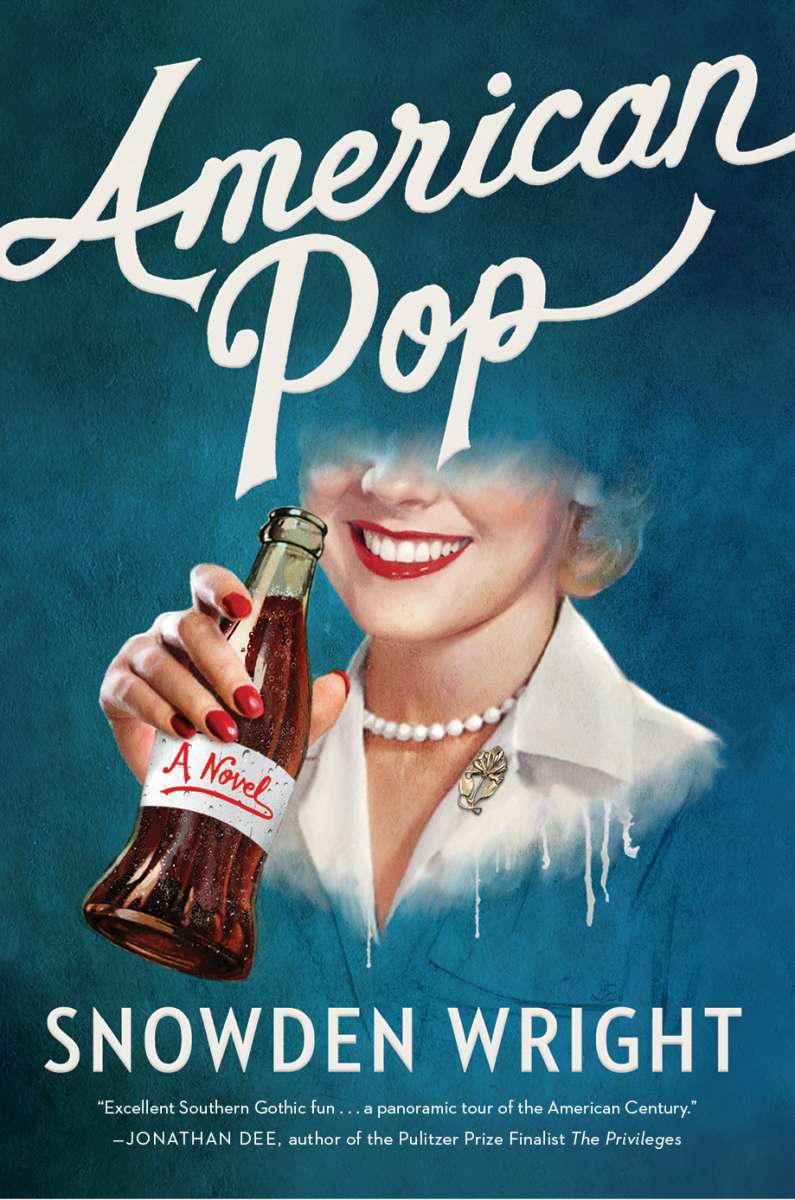

From American Pop by Snowden Wright, published by William Morrow. Copyright © 2019 by Snowden Wright. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.