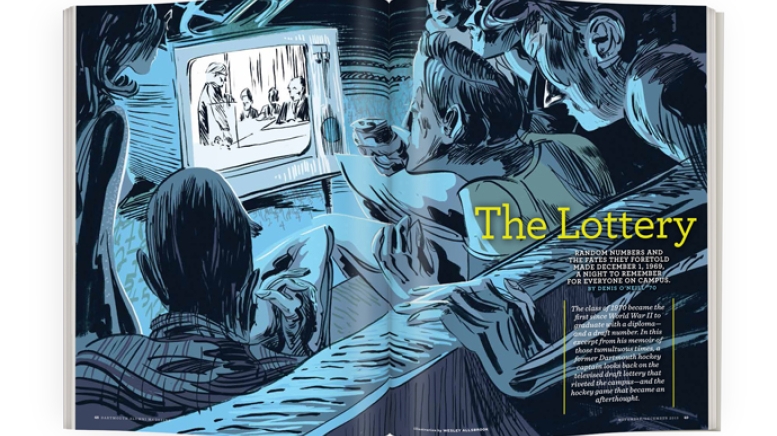

The class of 1970 became the first since World War II to graduate with a diploma—and a draft number. In this excerpt from his memoir of those tumultuous times, a former Dartmouth hockey captain looks back on the televised draft lottery that riveted the campus—and the hockey game that became an afterthought.

Danny awoke in the dark in his New Hampshire Hall room on the morning of December 1, 1969. Sleep had been fitful. He had dreamed of Birdie somewhere in Vietnam—a year removed from the first game of his last year in school, as far from ice as he could be. He remembered how Birdie looked that summer evening on the brink of going to war: scared…haunted…resigned. Danny felt a similar resignation. The road was about to fork, but the choice would not be his. He could hear his roommates’ heavy breathing. In theory they were all in the same boat, but for Ethan the inevitability of medical school provided him with a reliable life preserver. Russell always slept well. He had long since mastered the art of not worrying about things he could do nothing about—an enviable approach to life reinforced with a con man’s confidence in his ability to evade danger.

What Danny knew filled him with apprehension: That evening the first draft lottery drawing held in America since 1942 and the dark days of World War II would take place. By dint of a birthday, every male in America, aged 18 to 26, would be given a draft number from 1 to 366—an order in which they would be called up for military service in the following year—1970—to help win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people. Ironically, in its first game of the season the Dartmouth hockey team would play Norwich University—the military college of Vermont. The gates to Never Never Land—Birdie’s ominous recalibrating of Hanover—were about to be fully breached. And by a quirk of scheduling, the first salvo was about to be fired on the ice.

The event, at Selective Service national headquarters in Washington, D.C., was being broadcast on television and radio. Lives would change forever that night in ways that would stamp the class of 1970 across America as guinea pigs for a new era. The campus practically ticked with anxiety and apprehension. WDCR, the College radio station, was covering the event live from its Hanover studio. Every fraternity had converted its television room into a lottery mission control. In a setting as hokey as a bingo night at a Kansas Elks Club, 366 blue plastic capsules containing birth dates (and a leap year birthday) were placed in a glass bowl on top of a library stool in a very plain room at the Selective Service headquarters. One by one the capsules would be withdrawn by human hand, split open and the birth date within listed as a draft number in the order it was removed from the container. They would be recorded on a large board that had been set up with 366 numbers already listed. A sign atop the board read: “Random Selection Sequence, 1970.”

The potential for retroactive, delivery day irony was acute. “So,” Ethan said to his roommates and Molly, who had driven up from Northampton, Massachusetts, to support Danny, “say at 11:30 p.m., after four hours of labor, your mother decided to go for the C-section and you were born on that day, instead of the next if she had continued with natural childbirth. What if the day you were born on instead of the one you would have been born on gives you an unbelievably high or low number? How are you going to feel about that? C-section you go to ’Nam. Natural delivery you don’t. Or vice versa.”

Danny and Russell were only half listening. They were caught in a crossfire of their own—trying to think about a hockey game hours away, while contemplating a fate after college months away.

“Then there’s the question of twins,” Ethan went on. “What if one twin is born two minutes before midnight and the other two minutes after? How screwed up is that if one draws No. 7 and the other gets 344—and they’re twins born four minutes apart! You see how weird this might turn out?”

Russell peered at Ethan. He had trouble sharing his lotto fever calculations. “What do you care? You’re going to med school anyway, and that’s a six- or eight-year deferment so it doesn’t matter what number you draw.”

Ethan paced the room. “It’s just interesting, that’s all. Let alone life threatening, you know? I mean, some person is going to reach in and snag a ball and open it and it’s going to be your birthday, or Danny’s, and how weird is it your whole life hinges on that…after all the things you’ve done in your life that all of a sudden don’t matter. Important things, which all of a sudden—poof—don’t mean a thing. It’s schizophrenic, that’s all.”

The game that night was unique—a game that played out simultaneously on the ice and in the stands—where fraternity brothers with radios shouted out the birthdates as they were called and the corresponding draft numbers. “September 26th, 18! November 1st, 19!”

The brothers of Heorot had set up their lottery war room in the house library. The names of the seniors were listed on a poster board. Another poster board would chart all of the birth dates and their corresponding draft numbers. The event was of such importance Mugsy had set up a keg in the room so not a moment would be missed in beer transit.

Meantime, the majority of brothers who formed their own cheering section at the rink left Heorot with cans of beer in the pockets of their long, wool coats. This being a period of enlightenment in American education—a time when painted students with Mohawks could run around fires pretending to be Indians and security at sporting events did not deter cans of beer or bottles of tequila from being brought into those events—the men of Heorot were prepared to properly mourn or celebrate the twin competitions that lay before them: the game and the lottery. Win or lose, Dartmouth men knew the importance of journey.

On the television screen in the Heorot library, CBS correspondent Roger Mudd spoke in a hushed voice from the Selective Service headquarters. “Good evening. Tonight for the first time in 27 years the United States has again started a draft lottery.” Behind him Republican Congressman Alexander Pirnie of New York tugged up his suit sleeve and reached his right arm into the glass container of blue capsules. He pulled out a little blue capsule and cracked it open. Inside was the date: September 14.

T.P., standing beside one poster board in his ubiquitous “peace symbol” T-shirt, wrote “Sept. 14” beside the No. 1 at the top of a column of numbers. Mugsy scanned the posted birthdates of the Heorot seniors. No one was born on September 14. Mugsy pumped his arm—so far so good—unleashing a cheer from the assembled brothers.

Davis Rink, the ancient, barnlike arena across from Heorot, looked like someone had split a culvert in half lengthwise and set it on a foundation of bricks. There was very little heat, chicken-wire protective screen instead of shatterproof glass, standing room on either side, three tiers deep, a seating area at the far end and a smaller standing area at the end of the rink you entered. The upside was the ice was hard and fast and the home rink advantage pronounced, given the proximity of hostile fraternity factions and other Dartmouth students so close to the action. Taunts were the least of it: Frozen fish and chicken parts had been known to find their way into the vicinity of opposing players.

The game that night was unique—a game that played out simultaneously on the ice and in the stands—where fraternity brothers with transistor radios shouted out the birthdates as they were called and the corresponding draft numbers. “September 26th, 18! November 1st, 19!”

A student in a fraternity clump next to the Dartmouth bench angled a transistor toward the bench area so the players could be kept up to date between shifts. The Norwich bench, separated from the Dartmouth bench by the penalty box, could overhear the transistor radios from fraternities staked out on their side of the seating. Neither coach liked it, but neither could do anything about it. For the Norwich players the draft was more curiosity than anything else. Their degrees came with a commitment to serve. For the Dartmouth players the game on the ice was the second most important thing happening that night.

The Heorot contingent, some 20 strong, stood halfway between the Dartmouth bench and the end of the rink, bunched together like meerkats. Kendall, in his prep school camel-hair long coat, had a beer in one hand and a transistor radio in the other. “November 27th, 47!” he thundered, his eyes sparkling behind granny glasses.

There was a face-off just inside the Norwich blue line as he spread the news. The Dartmouth center, a junior, was bent over, about to take the face-off. He abruptly backed out of the face-off and straightened up. He shouted over to Kendall: “What number for November 27?” “47!” Kendall shouted back.

The player’s shoulders slumped in disappointment. He motioned his winger into the face-off position with his stick, all the while shaking his head, muttering obscenities. When the new face-off tandem had finally squared off, the referee looked around to make sure everyone was in proper position before dropping the puck. As the puck left his hand another fraternity voice boomed out: “August 8th, 48!” The Dartmouth face-off man looked up to catch the number. The Norwich center, unconcerned, steered the puck to his winger. The real game that night was not on the ice.

Ethan linked arms with Danny’s girlfriend Molly in the middle of the Heorot contingent. It was the second period. Nobody cared much about the score, though it was visible on the scoreboard above the seating area at the far end of the rink. Russell’s number had come up between periods: 85, not good. He didn’t get the bad news until they came out for the second period warm-up skate. He skated over to Ethan, who was pressed against the chicken wire. “Canada, roomie. 85. I’m really sorry.” Russell took it in stride. “One thing at a time, Slim. At least now I can concentrate on knocking over a few bodies.”

Danny, who was skating and stretching, looked over and saw Russell skate away from Ethan. He locked eyes with Ethan. Ethan shook his head solemnly, gave Danny a thumbs down. He held up eight fingers, then five. Danny muttered an obscenity. He picked Russell out of the skate around. His head was up; there was a fierceness in his gaze.

Midway through the period Russell saw the play developing and smelled blood. The Norwich defenseman collected a loose puck and skated behind his net to set up a clear. His left winger raised his stick to draw attention and circled back to pick up a pass. Russell, the right defenseman, skated slowly so the Norwich players figured they had room up the left side. Russell hesitated a second, to sell the retreat. Then he made his move, bolting toward the blue line. The Norwich defenseman skated out on the left side of the net and let the pass go—intending to lead his winger just as he completed his circle along the boards. The winger looked back to collect the pass.

At the precise moment the puck hit his stick, his head was angled back, not up ice. At that same instant Russell brought a fast moving 200-and-something pounds to the intersection of pass and player, shoulder first. The Norwich winger didn’t know who or what had hit him until he was on his back, looking up. The Heorotians, used to Russell’s trademark hits, unleashed a thunderous howl, stomping their feet and thrusting dozens of thumbs up, as was their custom. Russell savored the moment. The military may have hit him first that night, but true to his nature Russell had struck back.

Danny’s number was up on his third shift of the second period. December 13. Molly clutched Ethan’s arm when Kendall shouted out the date. Tears filled her eyes. “That’s Danny,” Molly said. Kendall shouted it first, but Danny didn’t hear as he was consulting with his center on where to draw the puck. “Danny!” Ethan shouted. Danny looked over with a stunned expression, like a deer in the headlights. “163!” Ethan held up a hand and wobbled it for Danny to see. The message: Not good, but not horrible. It would depend on the eligible men in his draft district.

Years later Danny could never remember who won the game (Dartmouth 5-4 in overtime). The aftermath, in the basement of Heorot, he never forgot.

The library at Heorot was empty and the keg long kicked before Danny and Russell showered and made their way to the house. The two poster boards were filled with magic marker scribbling: a list of every date with its corresponding draft number and another list of the 20 seniors with their lottery numbers. High and low brothers were indicated with asterisks—winners both, though only one was enjoying the distinction.

The basement of Heorot, always jammed after home hockey games, held more bodies than usual—as well as a function beyond the normal dispensary of beer and conversation: emotional triage. In a single, momentous evening the mood across campus had been irrevocably altered. For perhaps half the senior class, winter and spring semesters had morphed into an end game gallivant—a six-month hall pass to pursue studies or pleasure beyond the shadow of death. For the other half, including Danny and Russell and almost two-thirds of the Heorot seniors, a low- or middle-ground draft number reduced a one-time joyful college experience to a single, fear-driven focus: how to avoid going to Vietnam.

The emotional bookends in the basement were on visible display. Darren had drawn No. 361—his luck with girls seemingly carrying over into life’s other categories. He bought a keg for the house and drank as much of it as he could before passing out on his back on the bar top. His ankles were crossed, his hands were clasped together at his belt. Vomit stained the front of his shirt. There was a smile on his face some suggested might require surgical removal. He drew 361 and wasn’t going to war.

Roo, the brother who drew the shortest straw (No. 17) sat on a bench at the foot of the staircase across from No. 361. His eyes were red and tear-soaked. He was going to war unless he fled to Canada or shot off his big toe or fashioned some other deferment. He said as much over and over again, between sobs, consoled by his girlfriend Windy, who told him: “You can beat this. There’s time.” Fraternity brother T.P. leaned close to be heard over the chatter: “There’re all kinds of ways and deferments. I know people who know these things. They’ll help you.”

Danny sat quietly with Molly and Ethan and Russell and Henry behind the bar. Molly’s leg was hooked over Danny’s, her arm draped over his shoulder. No. 163 had left him in no man’s land. There was no comfort, only uncertainty. Even the voices suggesting a positive outcome were tinged with anxiety. Russell was ever stoic. The 85th birthday drawn, he was going to war if he let things play out. But it wasn’t in his nature. He would strike first, as he did on the ice.

“Maybe you two should go to Canada and play hockey,” Ethan offered. “You know? Kill two birds with one stone. Avoid the war and get a job.”

“Hear that?” Russell said to Danny. He draped an arm over his roommate’s shoulder. “Maybe, eh?” He delivered the “eh” Canadian style. He wrapped his other arm over Ethan’s shoulder and pulled him close. “You can be our personal physician, Slim. Think about it: The 404 Club reunited north of the border.”

“Goddamn Nixon,” Henry said softly, taking in the alternating expressions of relief and despair that filled the room on the other side of the bar. “It’s just a ploy. Put it on television, have draft-age kids draw some of the numbers. Give it legitimacy. Make it seem like we’re all in it together. What a crock.” He lifted his camera, focused and took a shot, documenting the whiplash frieze in that jammed, squalid place.

Somebody cranked up the jukebox, figuring music to be a balm for either lottery camp. Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” rang out with its easy beat, sweet vocals and carefree message. People sang along.

“Both my parents fought in World War II,” Danny said over the music, reviewing the military contributions in the family tree. “So there’s a family history. But this war….” He looked at Molly, who offered a brave face. Danny shrugged, We’ll see. Molly returned a more hopeful shrug, It’s not over til it’s over.

“(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” with its irresistible melody and laidback lyrics, overtook the entire basement. Everyone joined in, like trench soldiers in a World War I movie, adding their voices to “Silent Night” on Christmas Eve, comforted by their collective humanity.

Sittin’ here restin’ my bones.

And this loneliness won’t leave me alone, yes

Two thousand miles I roam

Just to make this dock my home.

Now I’m just go sit at the dock of the bay

Watchin’ the tide roll away, ooh

Sittin’ on the dock of the bay

Wastin’ time.

Danny’s mind reeled as Otis Redding whistled the song out. The voice he heard above the whistling was Birdie’s, reminding him that the real world was different. Danny leaned back, closed his eyes. More likely than not, he was going to war

Author’s Note: Dramatic license has been taken in this account of the draft lottery, but almost everything recounted here happened—either experienced by me or told to me. I have also compressed characters and given most of them new names to keep options open for anyone contemplating a late-life run for political office.

Denis O’Neill has worked as a journalist, short story writer and writer/producer for public television. He wrote the screenplay for and executive produced the 1994 movie The River Wild. He has three sons and lives in Beverly Hills, California. This story is adapted from Whiplash: The Way We Were When the Vietnam War Rolled a Hand Grenade into the Animal House. To read more of it and learn the fates of Danny and the gang, go to http://denisroneill.com.