In July 1969 I turned 14, and a few weeks later my family moved to Hanover. I soon befriended a classmate named Rob Kemeny, whose dad, John, was a Dartmouth math professor. A few months later John became the College’s 13th president.

Through the next few years I was often at the president’s house, hanging out with Rob. I interacted in passing with his parents and older sister Jenny but never spent any significant time with them. My purpose for visiting was purely recreational and included competing against Rob on what may have been the first video game ever created—side-by-side, bitmapped skiers carving their herky-jerky ways through gates on a scrolling slalom course. We also played a lot of bumper pool in the basement, air guitar to songs by Derek and the Dominos and the Eagles, and games of touch football on the front lawn with fellow Hanover High students.

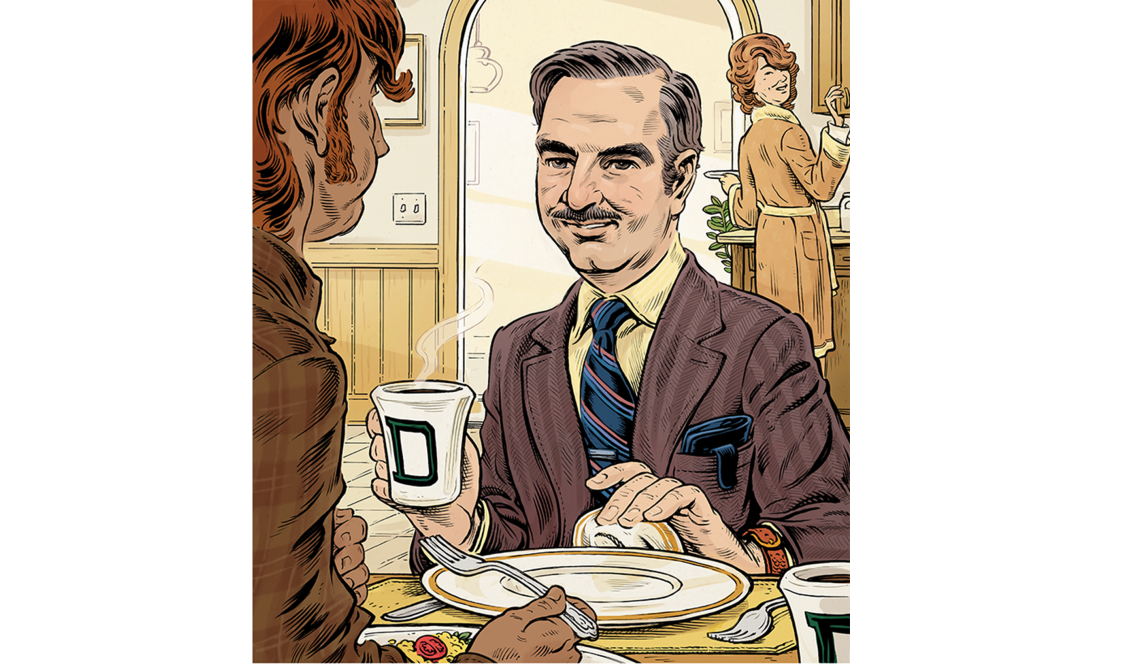

In March of our senior year, Rob invited me over for breakfast prior to driving to Concord, New Hampshire, to watch our high school hockey team compete in the state tournament. Imagine my surprise and delight when John Kemeny, in suit and tie, sat down next to me at the breakfast table. A few minutes later a yawning but ever vivacious Jean Kemeny, in a flowing dressing gown, joined us. I felt a bit like Holly Golightly in the opening scene of the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s who stares into the store’s windows, admiring the shiny objects before her, but that’s where the similarity ended. While Holly nibbled on a croissant and sipped coffee from a paper cup, I chowed down on scrambled eggs and bacon and glugged my coffee from a porcelain Dartmouth cup.

As an introvert—not to mention a bit starstruck at the moment—my utterances to John and Jean were limited to “Good morning” and “Thank you for having me.” Rob’s parents sensed my unease. Being experienced socializers, they turned on the charm and began telling stories on themselves. John noticed I had nicked myself shaving that morning. He related how, as a doctoral student who worked as Albert Einstein’s math assistant at Princeton, he was thinking about his thesis while shaving one morning, had a eureka moment, and gave himself a nasty gash. Rob then added that John’s subsequent dissertation was reputed to be the shortest in history—a single paragraph that concluded with a mathematical proof.

My overwhelming curiosity finally vanquished my innate reticence, and I asked John, “Why would someone as brilliant as Einstein need a math assistant?” His matter-of-fact reply: “Einstein wasn’t very good at math.” Apparently this is now common knowledge, but in 1973 I was gobsmacked.

Jean talked about moving from Princeton to Hanover—a town that had not yet installed its first traffic light—and how Dartmouth’s math faculty had a particular fondness for martinis, surreptitiously conveyed in thermoses into football games. She said John didn’t enjoy the martinis, which caused him considerable consternation. “I like gin, and I like vermouth,” John interjected, “so I couldn’t figure out why I didn’t like martinis.” It took quite some time, said Jean, sharing a smile with Rob, but eventually one of the world’s most brilliant men solved the riddle: He didn’t like olives. He switched to a twist of lemon, and order was restored in the universe.

Emboldened by my success as a questioner, I asked John why, after becoming president, he continued to teach math to freshmen each fall? He answered that he was first asked to teach when he was 18, that he loved teaching from the start and discovered he was good at it. He then paused for a moment. “To be a good teacher one must be a good communicator,” he said. To maintain his communication skills, he felt it was important to be reminded what it’s like not to know something, which is why he taught math to freshmen instead of to grad students. This practice, he added, was instrumental in his being able to persuade others that coeducation, which had launched six months earlier, was good for the College.

With breakfast done and dishes cleared, John headed off to work, Jean headed upstairs, and Rob and I headed to the game. (For the record, the Hanover hockey team went on to win the state championship that spring.) In September Rob, I, and 16 of our Hanover High classmates matriculated at Dartmouth. I never had the opportunity to share another intimate meal with John and Jean, but our paths did cross from time to time.

Why would someone as brilliant as Einstein need a math assistant?”

Fast-forward to the fall of 1992. I wrote a letter to John asking if he would be willing to speak at a long-running, summer lecture series in my small New Hampshire town. I fully expected to receive a polite rejection letter from his secretary. None came. Then early one evening about a month later, the phone rang. It was John.

He told me he appreciated the invitation, but he was no longer accepting speaking engagements. He then added that he was on oxygen and rarely made public appearances. I wasn’t sure why he was telling me this when it suddenly dawned on me: He was calling to say goodbye. The phone felt heavy in my hand.

He thanked me for being Rob’s friend and hoped I was having a good life. I said I was. Then, just as I had at that breakfast, I overcame my reticence and blurted to John that his advice about how important it is to be reminded what it’s like to not know something had stuck with me and served me well—as a college student, a husband, a writer, and now the father of two girls under the age of 3. I’ll never know if the man on the other end of the line, the one who so loved teaching, smiled. I’d like to believe he did.

A few months later, I attended John’s memorial service at Rollins Chapel. At the gathering afterward in Alumni Hall, Jean, Jenny, and Rob were being held prisoner by a seemingly endless receiving line that snaked around the room. Having lost my dad nearly 10 years earlier, I was pretty sure Rob could use a relaxant, so I sidled up behind him and asked sotto voce if I could get him a drink. “Yes!” he said gratefully. “A vodka martini.” I started for the bar. He grabbed my arm. “No olives. Just a twist.”

Jay MacNamee is a playwright and author of the recent children’s audiobook The Stuttering Magician. He lives in New Hampshire.