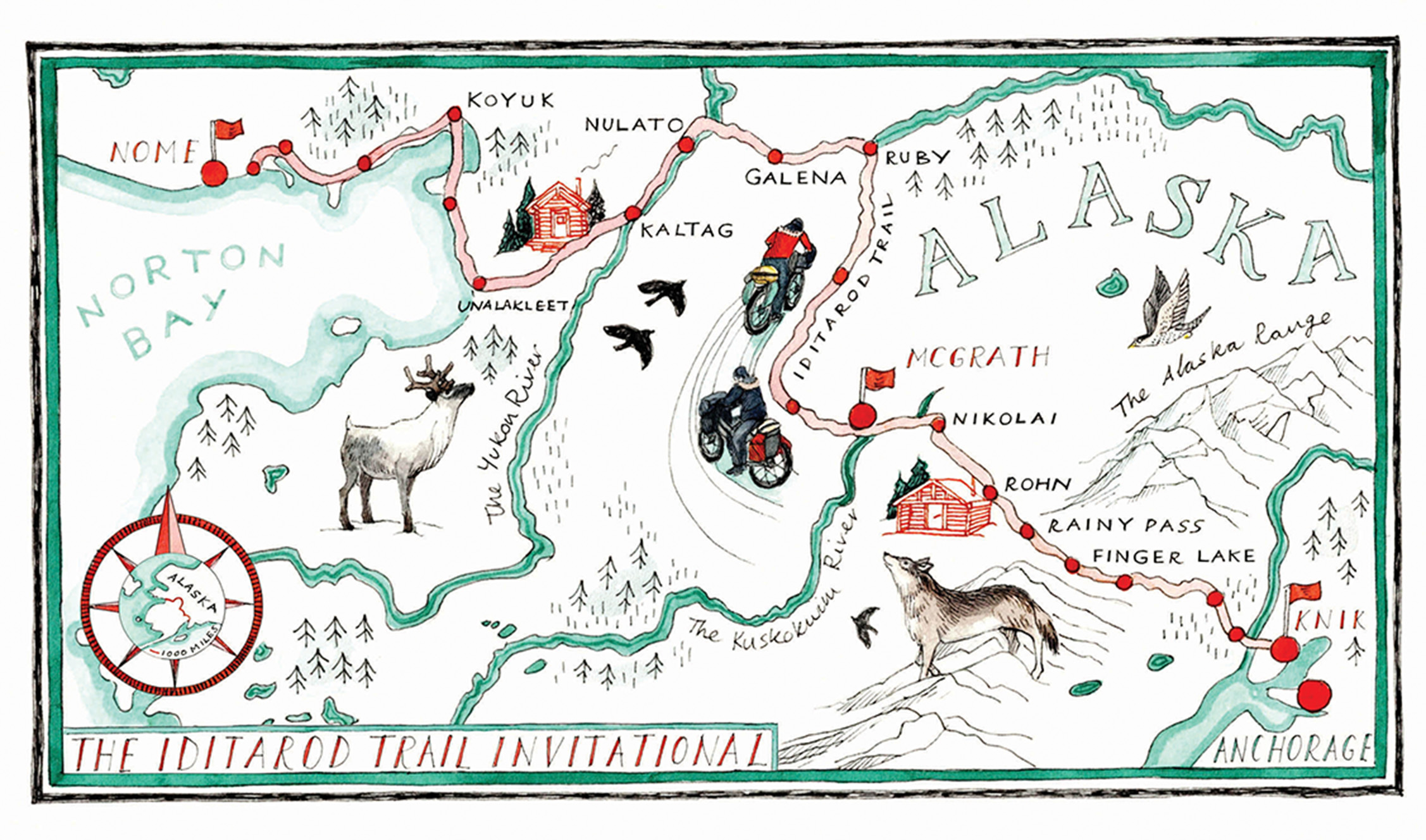

By the time she was in her mid-50s, Janice Tower had started to make peace with her “youth slipping away.” From her home on the outskirts of Anchorage, Alaska, she could look back at a lifetime of adrenaline-filled adventure and hard-core accomplishments. She had been a nationally ranked alpine skier, a Class IV whitewater kayaker, a world-class windsurfer. In 2000, at an age when most elite athletes start kicking back, she had entered her first mountain bike race, a 24-hour marathon in Moab, Utah, and earned a spot on the podium. Her résumé of endurance and ultramarathon mountain bike races stretched from South Africa, the Alps, Costa Rica, and the Canadian Rockies to the Iditarod Trail Invitational—a race that held a special place in her Alaskan heart. The ITI, as mountain-biking racers call the world’s longest winter ultramarathon, traces the historic thousand-mile Iditarod dogsled course from Anchorage to Nome. Tower had finished the shorter, 350-mile Anchorage-to-McGrath version of the race four times, the first back in 2002 before snow-friendly “fat bikes” were even invented.

She was resigned to having missed her chance at the thousand-mile ITI, something she’d long dreamed of attempting. The full course over the Alaska Range, across the subarctic interior, down the mighty frozen Yukon, and on to the Bering Sea promised extreme physical and mental challenge and extreme conditions, isolation, and beauty on a scale one could find only in a place such as Alaska. Attempting it was simply too much to ask of Tower’s beaten-up knees, which suffered badly from osteoarthritis.

She finally got around to having a total knee replacement at age 56, and then three years later had her other one done. She discovered she could go out and do things she hadn’t been able to in decades, including downhill skiing and hiking in the backcountry. The idea of the thousand-mile ITI across Alaska came back into play. “It was a rebirth of what was in the realm of possibility for me,” she says.

At the same time, Tower’s older brother, Matt Tanaka, had been steadily getting stronger as a long-distance mountain biker. He had started cycling casually around age 50, then became increasingly serious about it, especially in winter, as a way of staying in shape while exploring country that was inaccessible by other means. In 2019, Tower helped train him to join her on the ITI 350-mile version. They finished 10th.

In the following years, Tanaka entered the race as a solo rider, finishing once and scratching twice—all the while building confidence. “For me,” he says, “going all the way to Nome was out of the question, because it was too extreme—orders of magnitude more difficult than the 350. But the idea grew on me. It seemed the ultimate challenge. As I gained more experience, I became convinced I could do it.”

In his mid-60s, feeling “it was now or never,” Tanaka signed up for the longer race. He talked with his sister. She agreed to join him and ride together.

The Training

The ITI attracts elite endurance athletes from around the world who are prepared to walk, ski, or pedal—and push—their bikes across a thousand miles of Alaska wilderness through gale-force winds, whiteout blizzards, waist-deep snow, freezing rain, and temperatures that can swing 90 degrees in a matter of hours, from above freezing to minus 50. Up to 30 days out, with 34,000 feet of elevation gain, and few options for support or rescue, the race is regarded by many as one of the most challenging physical experiences on the planet.

Through the fall and into the winter of 2025, the siblings followed a daily training regimen designed by Tower, a USA Cycling- certified Level 1 coach, to prepare for the challenge. They tested gear on terrain and in conditions they might encounter on the trail to see what worked, maximize efficiency, and find the limits. How warm am I with my mid-layers when it’s 3 below zero? How fast can I organize my sleeping system? They trained during a warm spell on a river with standing water on top of ice and learned the exact depth to which their boots were waterproof. They rode one weekend at 17 below zero over the frozen lakes and swamps in the Nancy Lake area north of Anchorage. They rode up the frozen Skwentna River all the way into the Shell Hills, getting 70 miles of training on the course they’d be riding come February.

But south-central Alaska was experiencing another mild, low-snow winter—so-called “Pineapple Express” conditions—that made it impossible for Tanaka and Tower to train in real snow or truly cold temperatures. “We just took what the conditions gave us,” says Tanaka. “Just like we’d have to do on the course.”

What Tanaka could prepare for was walking. On his second attempt of the ITI 350, he had bailed after just a couple of days, when two and a half feet of new snow made riding the course impossible and forced him to push the bike. “I had trained for riding,” he says, “not walking.” At that time, he hadn’t walked or hiked for more than a couple of hours in years. In training, he walked four, then six hours a day, then pushed his mountain bike, then pushed it uphill fully loaded. “You’re successful when you train for the right goal,” he says. “We weren’t training to simply ride all the way to Nome—or to win. We were training for whatever it took to finish the race.”

He was apprehensive about facing weather he’d never experienced. He had biked at 20 below with 30-mile-per-hour headwinds, but he’d never been out in minus 50 with 50-mile-per-hour winds, conditions he knew existed on the 650-mile section of the trail between McGrath and Nome. The difference felt exponential. “I haven’t tested my gear in those conditions,” he said at the time. “I think it will hold up, but I don’t know for sure.”

In an interview for the 2023 documentary The Engine Inside, his sister called the ITI “three-dimensional—less a race to see who gets there first, more a test of experience, preparedness, and tenacity. It’s a win just to finish.”

She was concerned about the weight ratios. She and her brother are slight in stature (Tower would start the race weighing 120 pounds; Tanaka 134 pounds), yet they’d be riding and pushing the same 70-pound, fully loaded bikes as the bigger, stronger riders around them. The disproportionate burdens on their bodies would be multiplied by a thousand miles.

Both talked about the importance of good judgment, sticking to a disciplined rest schedule, and preserving energy. “It’s a race that favors 30- and 40-year-olds. I’m 63 and Matt is 66. We like to think that maybe we’re older and wiser,” says Tower—though some might question the wisdom of attempting to bike 1,000 miles across Alaska in the winter. Their requirements for rest and recovery were much higher than for younger riders. Nobody older than 62 had ever finished the race to Nome. The odds were against them.

Knik to McGrath

No one who knew the Tanaka family would have bet against either sibling. Matt and Janice’s parents, Jim and Rose Tanaka, were Nisei Japanese whose immigrant parents had worked in the mines and on the railroads in Wyoming. Jim and Rose had earned college degrees, lifting themselves out of the hard times and racism they’d grown up with in Wyoming. Rose had wrenching memories of seeing Japanese American families passing through the Cheyenne rail yards enroute to Wyoming’s Heart Mountain Relocation Center during World War II. Both had brothers who had survived action with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a heroic, mostly Japanese American unit that suffered some of the highest casualty rates of the war.

Jim and Rose married and settled on the outskirts of Anchorage when the city was still a frontier town and Alaska still a territory, built a homestead, and raised their family close to the land in the foothills of the Chugach Mountains. Just a couple of months before the start of the 2025 ITI, Rose, long widowed and still tending her home, died at age 95. Until two winters before, she had been snowblowing her driveway.

“Maybe a bit of that toughness comes down genetically,” says Tower. “Stubbornness, certainly.”

She and her brother grew up in Alaska’s wild country. They became expert alpine skiers (she competed for Dartmouth for a season before knee injuries cut short her career; he skied on the College’s development team). Nordic skier Viva Hardigg ’84 recalls training with both. “The Alaskans brought so much to the ski team: spirit, grit, endurance,” she says. “It was great running up mountains with them on Sundays.” When Hardigg learned that Tanaka and Tower were attempting the 1,000-mile ITI, she was not surprised. “I would expect something like that,” she says. “That’s a quintessentially Alaskan—and Dartmouth—thing to do.”

In the Ledyard Canoe Club, the siblings became whitewater kayakers. They were enthralled by fast water—the Kennebec in Maine, the southern rivers of Ledyard’s spring trips, the Ocoee in Tennessee, the Nantahala in North Carolina—and how paddling into vast, roadless nature touched a part of their Alaskan souls. Among the Ledyard paddlers, Tanaka was called “Mad Dog.” Summers, he worked on a salmon seiner to help pay tuition. He graduated with an engineering degree and a Class IV whitewater rating. Tower received her degree in policy studies three years later, then loaded everything into her little Chevy Citation, threw her kayak on the roof rack, and headed west. Across the country, she ran every spring runoff she could find until she got back home.

“I loved, loved my four years at Dartmouth,” she says. “I loved the history of New England, the tradition, the outdoor focus. But I yearned for big skies, big views, big mountains, big, big, big everything. I needed to get back to Alaska.”

By the time Tanaka and Tower found themselves at the starting line at Knik Lake, the Iditarod’s jumping-off point a few miles northeast of Anchorage, Tanaka had continued feeding his love of being on the water—kayaking, boating, fishing—alongside a long career as a civil engineer.

Tower had moved on from kayaking and become an accomplished windsurfer during the period when her husband, fellow Alaskan Steve Tower ’79, was doing his orthopedic residency in Portland, Oregon. They bought each other mountain bikes in 1992 for something to do when the wind in the Columbia River Gorge wasn’t blowing. She discovered she was uniquely built for endurance on two wheels.

She discovered, too, a purpose that went beyond adrenaline. In time, she converted her mountain-biking experience into a professional coaching business, created a youth program in Anchorage that introduced thousands of kids to riding, rallied funding and support for an extensive network of public riding trails around the city, and became one of the sport’s most visible ambassadors.

She and her brother were both methodical and rational by nature. They knew their bodies, trusted their willpower, and had anticipated—and prepared for—whatever the course and Mother Nature would throw at them. Despite their ages, they felt confident.

The conditions were nearly ideal at the start, and the pair made good time as they set out. Then, near the checkpoint at Finger Lake, just 130 miles into the race, Tanaka’s rear luggage frame broke. He jerry-rigged a repair with a nylon strap and baling wire. “No duct tape,” he said later, “but that was an Alaskan fix.” Tower used the satellite cell service to call the specialty shop in Anchorage that had outfitted them with their bikes for a replacement rack to be rushed by air to McGrath. The shop owner said he would do his best.

Between the siblings and the interior village of McGrath stood the rugged Alaska Range, including the 3,524-foot climb up Rainy Pass and the precarious descent through Dalzell Gorge. With each sweep of the pedals, Tanaka felt nervous about the makeshift repair.

Beyond Rohn and Farewell Lake, they rode up and down a series of low, wooded ridges, then broke into the Farewell Burn, site of a massive 1978 forest fire that had scorched a million and a half acres. The fire had opened up breathtaking views—wide to the hills west of McGrath, the summits of McKinley and Foraker looming above the Alaska Range far to the northeast. But the thumping, lumpy, tussock-filled terrain was brutal on the bikes.

Tanaka’s repair held up. But the effort getting across the burn sapped his energy. When they reached the 300-mile checkpoint at Nikolai on February 27, he was spent. The next morning, he ate only the oatmeal offered by the checkpoint volunteers—nowhere near the calories his metabolism required. Riding on a ribbon of black ice through the frozen swamp beyond the village, he had trouble keeping his eyes open. He began to hallucinate. The dark ice became a black, elevated walkway. Ghostly riders appeared and disappeared in front of him.

Tower recognized the signs. She calmly explained the physiology behind what her brother was experiencing, that his glycogen reserves were severely depleted. She told him his brain was shutting down—a natural response to slow a body so the liver can begin to restore glycogen levels. He needed to ramp up his glycemic intake, she told him, and ease back the energy he was giving his pedals. Tanaka ate some sugar candy and ripped open a packet of coffee granules and dumped them in his mouth. He sucked down the coffee with water from his Camelbak hydration pack, then had another. He slowed his pace.

When they reached McGrath 54 miles later, Tanaka felt stronger. “That’s the nice thing about riding with a partner,” he says. “If you’re working together as a team, you can balance each other’s energy when one of you is flagging and the other feels strong. You can sustain each other and keep each other going.”

The replacement part from Anchorage was waiting.

McGrath to Ruby

At McGrath, the race was done for the 84 athletes who had entered the 350. The 20 riders pressing on to Nome now faced an additional worry. At the last minute, organizers of the Iditarod dogsled race had shifted the traditional Anchorage starting point farther north, to Fairbanks, because of poor snow conditions—just the fourth time that had happened in the race’s history. The relocation had serious implications for the remaining ITI riders: They would have to follow a little-used northern route and intersect with the Iditarod dog teams at the Yukon River in Ruby, 184 miles away. It would be a dicey move.

Fortunately, that northern route had been broken by snow machines in an annual race called the Iron Dog a week before the ITI start. Tanaka and Tower knew there would be a trail to follow—or at least what had been a trail in the not-distant past. By the time the ITI racers were coming through, there was a good chance that snow and wind would have covered over the tracks laid by the machines. The two riders hoped, at best, for a firm base beneath the snow.

They set out on the stretch to Ruby—a forbidding, empty landscape of endless climbs over domes and through the thinning black spruces and birches of the far northern boreal forest. Much of the route was exposed to wind and blowing snow. Some years, deep or drifting snow forced ITI racers to push bikes nearly the entire section.

The pair’s good luck with weather ended on the first night out of McGrath. Tanaka and Tower awoke to 3 fresh inches of snow, and Tower thought, Okay, here it goes. We’re going to be pushing our bikes to Ruby.

Their 5-inch-wide tires found purchase, though. The trail, for the most part, was still rideable. The weather cleared.

They rode slowly but steadily in silence, surrounded by the crystalline vastness of the Alaska interior. Now and then they saw wolf tracks. “Magical,” Tanaka says later. Occasionally, they hit sections of trail that had been blown in and had to dismount and push. Tanaka would remember this section of the race as a relentless slog, one that forced him to hyperfocus on the moment in order not to be overwhelmed by the enormity of all that still lay ahead. He found himself falling into a mantra. How do my legs feel? Am I hungry? Am I tired? Is my cadence right? How am I going to get up this next hill? In a way, he recalls, it was meditative.

Tower, for her part, was in a happy place. Hard-willed and competitive, she excelled at sports that reward dogged, grinding endurance. Pete Basinger, a seven-time winner of the ITI, says, “I’ve been on countless adventures with Janice where she takes a tumble, draws blood, and just gets up, wipes herself off, and keeps plugging along. She’s incredibly tough.”

The interior monologue running through her mind on the difficult stretch to Ruby tried to calm that competitive drive. For much of the race, Tower and Tanaka had been within striking distance of a pair of younger racers, including one of the few women riding all the way through to Nome. Tower had noticed that she and her brother were moving at a higher traveling speed than the pair ahead of them, but they needed to take more frequent and longer rest breaks for recovery. “In the back of my mind,” she recalls, “I was thinking we could probably beat them if we wanted to. I was really happy I could override that impulse and say, Nope. Stick to the plan. You’re in this to finish. You’re in it to have a great experience with your brother and see these parts of Alaska you’d never get to see if not for this race.”

They made it to the village of Ruby on March 4. All told, they had been forced to push their bikes only 8 or 10 miles out of the total. “Not a big deal,” Tower says.

Tanaka took advantage of the cell service to post an update to his Facebook page. Dozens of friends and Dartmouth classmates following their daily progress on a race-tracking website offered encouragement; many shared how inspired they were by the siblings’ progress. Tanaka posted: “Didn’t take a lot of photos as this 200-mile section was really tough. McGrath to Ruby was a tough but beautiful section. A little more Type II fun, but glad to have rested a lot and suffered less. So. Many. Climbs!!!”

Nome or Bust

Down the wide Yukon River they rode. The temperatures rose into the mid-30s—the warmest they’d encounter—and the snow turned to mush, slowing their travel. It took them 13 hours to make the 50 miles to the checkpoint at Galena. Tower called the day “soul crushing.”

Just before sunset the next day, March 7, the leading dog teams of the Iditarod caught up with them on the Yukon between Galena and Nulato. Tower and Tanaka heard them before they saw them, the yep-yep-yep of the huskies emerging out of the vast nowhere behind them. The riders pulled over and let Michelle Phillips skim past them, chased by the race’s eventual winner, Jessie Holmes. Tower stuck out her hand, and Holmes gave her a high-five. The riders shared the trail with the mushers from here on out. A blessing in terms of finding their way, and Tower, especially, felt the privilege of being embedded in one of Alaska’s greatest events. Some nights, sharing a community center shelter or sleeping-bag-lined school gymnasium, they traded stories with the mushers and felt connected by something hard and rare.

With winds building, Tower and Tanaka made a bold decision in Kaltag to try for Unalakleet on the coast in one big push—77 miles in 14 hours. The trail had frozen with the dropping cold, and they traveled fast. They rolled into the village by headlamp, slept like the dead in a warm building, and celebrated the next day at Peace on Earth Pizza.

The real wind came later that afternoon when they reached the sea ice at the wide frozen sweep of Norton Bay. A sustained north wind whipped off the Bering Sea, swirling snow into a ground blizzard. Trail stakes and spruce boughs marked the course, but visibility dropped to zero for minutes at a time. Crossing that bleak, howling expanse, buffeted by the wind, it was Tower’s turn to struggle. She wasn’t as fast a walker as Tanaka. She pedaled as fast as she could in her lowest gear and tried to stay riding, spending too much energy, while Tanaka methodically trudged onward ahead of her, pushing his bike, feeling pushed himself but comfortable after months of training for just this kind of walking. The temperature hovered in single digits—not the cold that could flash-frostbite you in a few seconds’ exposure but bitter with the wind chill.

The gusts rose as the day wore on, reached gale force, and began blowing Tower off her bike. They were too far across the 29-mile crossing to the shelter at Koyuk and couldn’t turn back.

Tanaka stopped and the two assumed new positions—now he walked in front of his sister so close they could touch. With Tanaka serving as a windbreak, Tower found just enough relief in the headwind that she could push her bike and maintain energy. They reached Koyuk after 14 hours and felt like celebrating.

One hundred and seventy-one miles away from Nome, they both let themselves, for the first time, start thinking they would finish. “We shifted into tourist mode, really,” Tower says. “The coast that far north is devastatingly beautiful. We knew we would never see it again. We wanted to savor every last minute of it.” From that point on, they slowed their pace, traveling only in daylight, resting fully at night. They were content to wear the “red lantern,” a racer’s term signifying the final finishers to make it.

They felt the odd sensation of being nostalgic even before the trip ended. Their minds wandered back to the generosity of the villagers along the way, gatherings that welcomed them, offerings of moose soup and cranberry cakes and reindeer stir-fries, riding beneath an amazing full moon, the eerie howling of distant wolf packs, shimmering northern lights and intense purple-and-salmon-pink sunsets. They thought of returning home to their side-by-side houses in Anchorage, Tower to her first grandchild. Dartmouth flitted through her mind: John Ledyard, class of 1776, and the College’s history of explorers and adventurers.

They talked about their mom.

Side by side on a bluebird, 10-degree day in Nome, 21 days after setting out, they crossed the finish line together.

View additional photos from their journey in our photo gallery.

Jim Collins, a longtime contributor to DAM, lives in Seattle, where he teaches journalism.