It started when the mother of Andy Potter ’91 sold her house. In cleaning out her attic, she came across some family letters in a box, which she sent to her son. In one of them, Potter’s grandfather mentioned something about helping with a Halliburton museum.

“I asked my dad [Hop Potter ’64] about it,” Potter said, “assuming that Granddad had some random relationship to the Halliburton company. Out tumbles this unreal, unbelievable story about a Chinese ship called the Sea Dragon and some incredible adventure sailing across the Pacific in 1939 with Richard Halliburton, a guy I had never heard of. My dad said that Granddad got cold feet at the last minute and decided not to go. The Sea Dragon sank.”

It turned out that Andy’s grandfather, along with two other Dartmouth men, played a part in the once-famous Sea Dragon expedition, and it changed his life.

John Potter ’38, known to all as “Brue,” was a maverick. His academic strategy, according to his son Rust (brother of Hop), was to research one intriguing fact that wasn’t in the lectures and books on the syllabus and drop that into his final paper. He loved pranks. He once caulked shut a bathroom in his dormitory—Streeter—and turned on the shower, making a swimming pool—until he let the water run out down the hall. He rigged up a fishing pole with a golf ball on the end of the line and on road trips to Smith in a convertible would ply the ball like a fish, scaring drivers behind him. He could mimic people and almost any mechanical sound. Senior year he was voted the class “Hot Dog.”

Brue was a golden boy, handsome and carefree. And wealthy. In the 1830s his great-grandfather, Thomas Potter, started what became the country’s largest oil-cloth and linoleum factory in Philadelphia. Brue’s great uncle became U.S. minister to Rome, and Brue’s aunt and grandmother survived the Titanic disaster. A French major, Brue spent his sophomore spring studying at the Sorbonne. In the summers he sailed a so-called New York 40—a 65-foot ketch—around the waters off Mount Desert Island in Maine. “When I worked the class of 1938’s 50th reunion,” Andy said, “all his classmates would say, ‘Potter? Oh, yes, he was the good-looking one.’ ”

Some of the glamour came from his longtime girlfriend Ann Hopkins, daughter of Dartmouth President Ernest Martin Hopkins, class of 1905. A beautiful, smart woman, Ann was crowned the Winter Carnival Queen of the Snows in 1936, her sophomore year at Smith. They had an on-again, off-again relationship since meeting in Southwest Harbor on Mount Desert when he was 15 and she was 12.

After graduation Brue planned to sail around the world. He got a crew together but the voyage failed. Brue then talked with Zola Halliburton, a Wellesley College woman who also spent time on Mount Desert. Zola told him about her cousin Richard Halliburton and his harebrained plan.

Like Andy Potter, most people today have no idea who Richard Halliburton was. A 20th-century version of John Ledyard, class of 1776, Halliburton skipped out during college, leaving Princeton on a freighter bound for Europe. In the 1920s and 1930s Halliburton wrote seven best-selling travel books about his adventures across the globe. He gave hundreds of sold-out lectures—at one point his publisher estimated that he had spoken to more than 3 million people in 14 years.

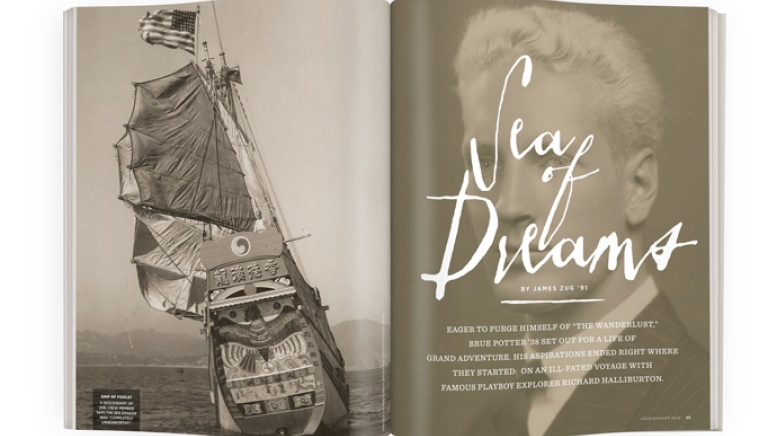

In the late 1930s Halliburton concocted a plan to sail from Hong Kong across the Pacific in a junk, an ancient Chinese sailing ship. He planned to arrive in San Francisco in time for a version of a world’s fair, the Golden Gate International Exposition.

Like Ledyard, Halliburton lived beyond his means and couldn’t finance the expedition on his own. With the help of Richard Townshend ’23, Halliburton formed a corporation to raise money. When he heard about Brue Potter, he knew he had the perfect sailing companion. In July 1938 Halliburton wrote his parents: “Have a telegram today from a young beau of Zola H—very rich and loves boats—he’s hell-bent to go with me, but I don’t know how much he’s willing to invest. Maybe all the rest I need.”

Brue jumped at the chance to join Halliburton. The first book he ever read was Halliburton’s 1926 The Royal Road to Romance and, as he told a newspaper, he “wanted to purge myself of the wanderlust.” They struck a deal: $14,000 for three Dartmouth men to join the adventure.

One was a good friend, Bob Chase ’39, a rising senior. The other was Gordon Torrey ’37, a guy Brue knew vaguely from sailing circles in Maine who had left the College after sophomore year. One afternoon in the summer of 1938, Torrey walked into the Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston to have a drink at the Merry-Go-Round bar. He ran into Brue Potter and Bob Chase, who were sitting at a table with Zola Halliburton. The deal was done.

In the end the Dartmouth men put up more than half of the $26,500 Halliburton raised. Without them, the ship wouldn’t have sailed.

After learning about the Sea Dragon from his Father, Andy Potter asked his aunt and uncle what they knew. Rust Potter, Hop’s older brother, remembered he had seen a 1980s VHS video. He dug it out and mailed it to Andy last year. The footage from 1938-39 allowed Andy to see his grandfather in a new light. “I had always thought of him as a sad person, living alone in this small apartment in Miami, not doing much,” Andy said. “Here he was young, handsome, traveling the world.” Brue and Chase filmed scenes from their boat trip through the Panama Canal and on to Honolulu and their flight from there to Hong Kong.

When they arrived in November 1938, the Dartmouth men discovered a tense situation. The Sino-Japanese War was raging, and Hong Kong was swollen with refugees. Halliburton, instead of buying a ship, had decided to build his own, the Sea Dragon, from scratch. The expedition was delayed.

Preppy and wide-eyed, the Dartmouth men goofed around. The whole trip was a lark. As DAM reported in January 1939, “Leave it to Brue to pick up some junk.” They roamed around the British colony, filming temples, street theater and the funicular tramway up Victoria Peak.

Paul Mooney, Halliburton’s lover, wrote of the Dartmouth men: “One boy a Connecticut Yankee of the worst [sort]; another longing for his habitual background of zebra stripes at El Morocco; still another fresh (how!) from Dartmouth and full of anti-Roosevelt jokes.” Halliburton, on the other hand, seemed to like the Dartmouth men. He wrote that Brue and Chase were “jewels,” and he appointed Brue first mate and Torrey second mate.

On February 4, 1939, the Sea Dragon sailed with a crew that included Brue and Chase. Torrey had gotten sick and was in a Hong Kong hospital.

Around noon on the second day, a massive storm crashed into the junk. It grew so rough that it took two men to handle the tiller that steered the ship. They turned on the diesel engine, but the wind and waves kept pushing the top-heavy junk backward.

At some point Brue retreated to his cabin below in the bow of the ship, complaining of a fever. The cause was—and remains—a bit of a mystery. Halliburton, in a newspaper article, wrote: “Potter, our first mate and the most experienced sailor aboard, in struggling with the mainsail boom, ruptured himself.” Brue’s children remember a giant scar, but disagree about where it was on his torso.

Brue had a high fever and for two days he couldn’t eat or drink. Halliburton debated whether to go on or retreat. “One more look at Potter’s flushed face and fevered eyes,” Halliburton wrote, “and we voted to turn around. A life—and a very fine life—might be at stake. So we swung the tiller with a mighty swing, spun the ship about and set our course back to China.”

They crept back into the Hong Kong harbor after six days, and an ambulance took Potter to the hospital. He recovered without surgery. In the 1980s Torrey told a Halliburton enthusiast: “They should have thought up a better explanation than ‘was struck by a boom’ to account for Brue’s coming ashore. He was the only one on board who knew enough to avoid a swinging boom.”

What brought the Sea Dragon back might have been not a boom but venereal disease, specifically, gonorrhea. It was highly prevalent among the prostitutes in Hong Kong. Gerry Max, a biographer of Paul Mooney and author of a forthcoming book on the Sea Dragon expedition, thinks both Brue and Torrey had it. “There they were,” Max said, “young men, killing time in a port city. Potter had all the symptoms.”

The obfuscation makes sense. “I remember him saying he was put ashore from the junk voyage because the huge boom whacked him in high winds, causing a severe back injury,” said Brue’s daughter, Jessie Kingston. “I can understand why a father might not want to tell his daughter if it was due to some version of VD.”

The disease (or injury) saved his life. While Brue and Torrey recovered in Hong Kong, in early March 1939 the Sea Dragon left a second time for San Francisco. Of the Dartmouth men, only Chase was on board.

Three weeks later, about 2,400 miles east of Hong Kong, the junk ran into another storm and lost radio contact. On March 30 The New York Times reported: “Halliburton Is Missing.” In April the U.S. Navy ordered an aircraft carrier to search the area. They found nothing.

Brue and Torrey recovered their health and in the spring returned to America. Torrey seemingly suffered few after effects of the experience. He was back in China a few months later, working for Texaco. After spending the war years in Asia (with some hair-raising close calls during Japanese attacks), he returned to the United States, had six children and led a contented life. “He lived a normal, happy life. He didn’t talk much about the adventure,” said his daughter, Sally Alley. “He did say he came down with smallpox in Hong Kong and that was one of the reasons he didn’t go with Halliburton.” The other reason? “The Sea Dragon was completely unseaworthy,” she added.

Torrey and Brue spent their summers on the same island in Maine, but never saw each other or communicated again. Torrey died in November 1992. For some, a near-death experience can inspire a retreat to the old and familiar; for others, it can lead to a foxhole promise to never live a dull, quotidian life. The Halliburton episode might have cured Brue of his wanderlust, but not his maverick ways.

Upon his return everything initially went smoothly. In August The New York Times reported that he was engaged to Ann Hopkins, and in September 1939 in the President’s House on Webster Avenue they were married. During WW II Brue served with the U.S. Navy in Bombay, India, as an attaché to British naval intelligence (another family legend involves Brue hitting golf balls from the top of his hotel there); Ann lived in Hanover with their two small sons.

After the war Potter got a job as a civilian with the Navy in Washington, D.C. Once he came home in the middle of the day, saying he had gotten fed up with his superiors and quit. The family moved to Darien, Connecticut, where Ann’s uncle Robert, class of 1914, lived. There Potter eschewed the standard upper-class routine of commuting into New York City for a job on Madison Avenue or Wall Street. Instead he started a general contracting company that did excavation and heavy landscaping. “While my mother wanted to go to cocktail parties,” says Rust Potter, “my father was bulldozing land and knocking down old chicken coops. My mother said to him, ‘You’re just a rich guy with dirty pants.’ ”

Brue, despite having young children, began spending the winters alone in Florida, where he ran a boat chartering service and played a significant role in the 1958 and 1962 America’s Cups.

In 1963 Ann left Brue. He moved to Florida full-time and continued his charter service until fire ravaged his boat in 1970. “The wind went out of his sails with the divorce,” says Rust Potter, “and the boat burning was devastating.” In Miami he rented a small apartment at a private club with a marina. He played a little tennis but was increasingly withdrawn. His hearing worsened. He never remarried. He died in December 1996, 34 weeks after Ann died.

James Zug is a regular contributor to DAM. He lives in Wilmington, Delaware.